Anna, the narrator of Lydia Millet’s new novel, Sweet Lamb of Heaven, goes on the run from her husband, an Alaskan businessman named Ned. With her 6-year-old daughter, Lena, in tow, Anna stays out of the system, albeit not entirely off the grid, moving around a lot, laying low, and carefully tapping a modest family inheritance. By the time the novel starts, she and Lena have holed up in a rundown Maine motel whose gentle proprietor has a penchant for taking in strays.

That’s a serviceable if not particularly original premise for what turns out to be an extraordinary metaphysical thriller from one of America’s most inventive novelists. Sweet Lamb of Heaven’s woman-in-peril plot at first seems to lack the confidence of its melodrama. Ned isn’t abusive, merely cold and neglectful, and when Anna first left him, he barely minded the loss of his wife—“He’d been indifferent to me for a long time, as he’s indifferent to most people who aren’t of use to him”—or the daughter he never wanted in the first place. But then Ned decides to launch a career in politics, and since his platform features a Sarah Palin–esque appeal to the “sanctity of every human soul” and “the greatness of the American family,” he needs to reassemble his own family for the requisite voter-friendly photo ops and meet and greets. Ned’s slogans, Anna thinks, “felt like objects to me—prefabricated items he had purchased quickly in a store, items he was busily stuffing into his shopping cart without close scrutiny.” But she has no doubt he will try to find a way to force her to comply, and she soon learns that she has underestimated the extent of his reach.

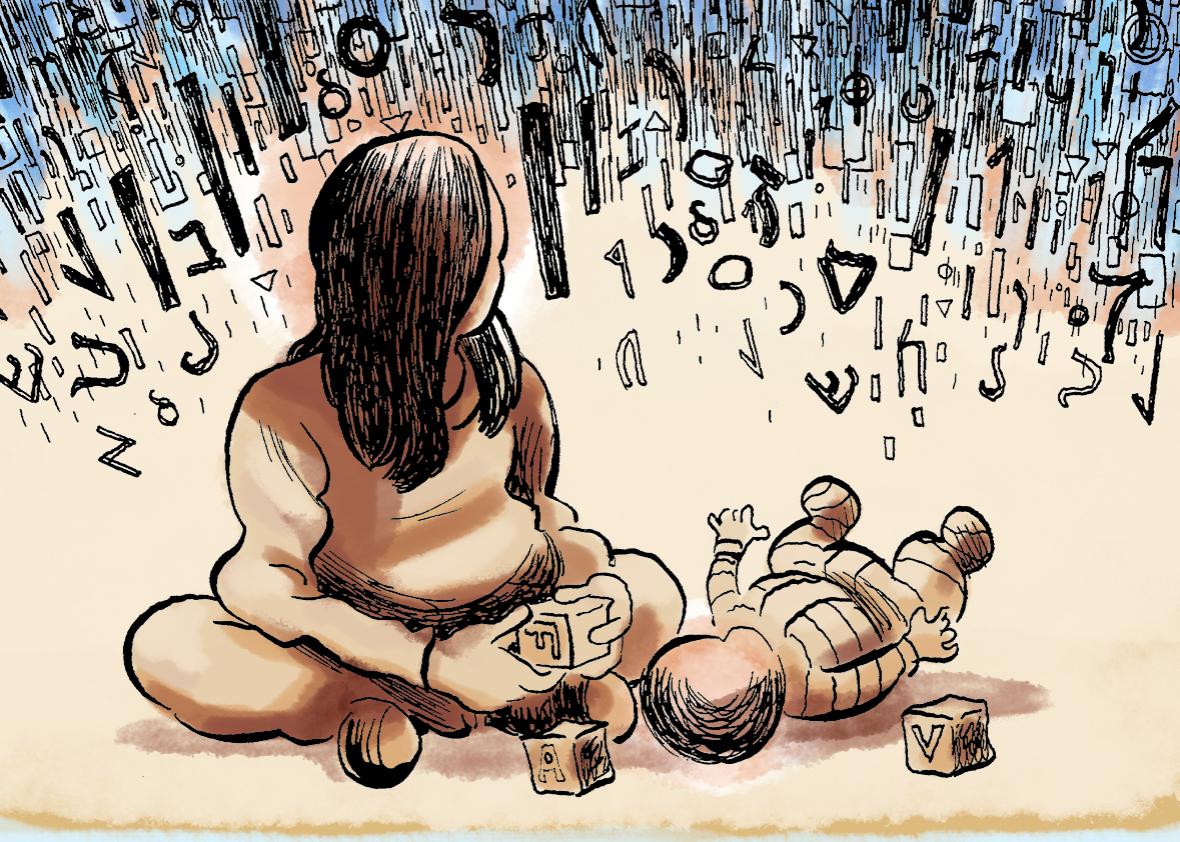

There’s also another, more enigmatic storyline running through Sweet Lamb of Heaven. During Lena’s infancy, Anna has an uncanny experience. Whenever the baby is awake, Anna can hear a continuous stream of words, a voice that has the “appearance of fluency in all tongues and gave an impression of encyclopedic knowledge.” She rifles through a litany of diagnoses and explanations—psychosis, possession, some perplexing technological freak—until she finally settles on the hypothesis of unexplained but nonpathological hallucination. The voice goes away when Lena speaks her first word, but not before Ned hears it too for a single, deeply unsettling moment. Furthermore, as the novel progresses, Anna discovers that the growing collection of motley guests surrounding her in the motel have all had similar experiences.

This is the skeleton—and no small amount of the flesh—of a Stephen King novel. (Surely the Maine setting is no coincidence.) The coiling tension as Anna’s efforts to elude Ned reveal his seemingly superhuman powers, the mystery of how the coalition of misfits at the Wind and Pines has come together and why, the intimations that far more may be at stake than just the fate of a single family—all of these elements click into place to form a sturdy narrative engine whose momentum, however familiar it may feel, proves irresistible. It propels the reader toward the expected apocalyptic confrontation between good and evil. But Millet’s fiction inhabits a different moral universe from King’s. In his novels, the nature of evil goes largely unquestioned; what concerns King is the task of summoning the courage to confront it. Sweet Lamb of Heaven uses the same epic devices to put forth a new idea of horror.

Jade Beall

Even when it’s not explicitly religious, most horror fiction is shaped by Judeo-Christian mythology and tends toward the operatic. In Sweet Lamb of Heaven, anything overblown generates a pleasing friction with the dry, skeptical wit that is Millet’s trademark. As soon as the story begins to inflate with signs and portents, Millet fingers her needle. “Conspiracy theories are a mostly male hysteria, it seems to me,” Anna observes. “That style of paranoia isn’t my own—it has a self-importance I don’t relate to. Even now, when I know for a fact I’ve been conspired against, it’s hard for me to believe in conspiracies.” Millet has a way of twisting a sentence from the histrionic toward the blandly matter-of-fact that can be very funny. “So my fear has turned mostly to anger, which is much easier to live with,” Anna reports as her conflict with Ned develops. “I see now why it’s popular.”

Nevertheless, Millet is quite serious with Sweet Lamb of Heaven, and when she wants to, she can unleash a bladelike lyricism: “We watch movies, read books made glamorous by black-and-red palettes of horror, the hint of an otherworldly malice running like quicksilver through the marrow of our bones. We like to call the dark rumors demonic, like to have monsters to fear instead of time, aging, the falling away of companions.” It’s true, we have an insatiable appetite for end-times entertainment, where the heroes face towering threats so much more spectacular than the mundane diminishment that awaits us all.

And yet, ironically, the world really is in peril, its fate hanging in the balance. We are faced with a doomsday scenario that most of us routinely choose to ignore, as well as a drumbeat of lesser oblivions. (Several of Millet’s recent novels have dealt with endangered species.) As a novelist whose central subject is humanity’s vexed relationship with the natural world, she must find this blind spot perverse. Here is our chance to be heroic ourselves, to rescue the planet, or at least to make a credible last stand. Instead we prefer to stay home and watch other people battle a pretend apocalypse on The Walking Dead.

So Millet gives us a new paradigm; her adversary isn’t horror’s usual bad guy, an atavistic entity hell-bent on destruction for its own sake, but the modern world’s infatuation with manufactured, convenient sameness. The showdown still comes decked out in all the suspenseful trappings we love best—a plot filled with surveillance and intrigue; a terrifyingly malevolent antagonist; an endangered child; a ragtag crew of brave resistors—but the soul of humanity is only one modest portion of what’s at stake. Her vision of the good is transhuman. In opposition to Ned’s cold, hollow will, Sweet Lamb of Heaven champions the fractal beauty of the chaotic and fecund, “the spirit and expression of all creatures and all people, their cultures and tongues and arts and musics, from the vaunted to the unknown … what was organic and alive, the broad, branching tree of evolution that was history and biology and all kinds of astonishing bodies full of ancient knowledge.” What does it take to make these things seem worth fighting for, you can almost hear the novelist ask. Good question.

—

Sweet Lamb of Heaven by Lydia Millet. W.W. Norton.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.