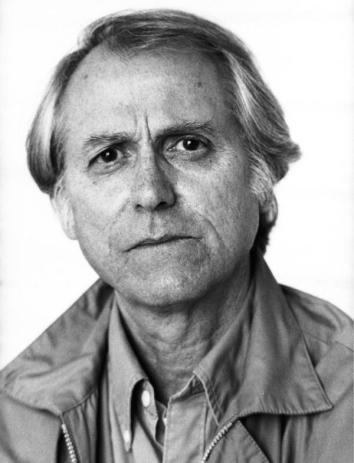

Say what you like about Don DeLillo, but you always know where you are with him. With DeLillo you are always, in one way or another, at the end of the world. In his new novel Zero K, you know where you are before you’ve even had a chance to ask, thanks to the book’s first sentence: “Everybody wants to own the end of the world.” As an opening gambit, it presents a compressed essence of its author’s stylistic and thematic dispositions: the merging concerns with capitalism and catastrophe; the post-religious eschatology; the stylistic signature of declaratory evasiveness, of plainspoken ambiguity.

The man who speaks these first words is named Ross Lockhart, a billionaire in his 60s who originally got rich off “analyzing the profit impact of natural disasters”—the sort of honest days’ work your standard DeLillo character has long tended to favor. Lockhart’s words are recalled by his aimless son Jeff, our narrator, as he’s chauffeured in an armored vehicle across the plains of Kyrgyzstan toward a secretive compound in which his terminally ill stepmother Artis is soon to be suspended in a cryonics pod, in the hope of eventual resurrection by scientists of the future. We’re barely a chapter into this thing, in other words, and we are already deep in DeLillo country.

Death and technology have, for decades now, been converging concerns in DeLillo’s fiction. “This is the whole point of technology,” as one character puts it in 1984’s White Noise. “It creates an appetite for immortality on the one hand. It threatens universal extinction on the other. Technology is lust removed from nature.” DeLillo’s previous novel, 2010’s Point Omega, took its title from the idea of the Omega Point, the French paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s theory about the eventual merger of humanity and technology. For the past two years I’ve been writing a book about the transhumanist movement and related topics. On several occasions during the reporting—not least while touring an actual cryonics facility in Scottsdale, Arizona±I found myself wondering what Don DeLillo might make of the whole business. It’s rare that a question of this sort receives an answer as direct and literal as Zero K.

The Kyrgyzstani compound—located, as the skeptical Jeff puts it, “at the far margins of plausibility”—is the desert outpost of a futurist quasi-cult called the Convergence. For all its sci-fi strangeness, the group reflects the ideas of actual Silicon Valley immortalists like Peter Thiel and Ray Kurzweil, soothsayer of the Technological Singularity: It offers a vision of eternal life to its wealthy benefactors, a chance of outmaneuvering mortality through applied science and applied capitalism. “The pod would be his final shrine of entitlement,” as Jeff reflects after a bitter argument with Ross. The reason for that bitter argument is this: Ross, unable to face the loss of Artis, has decided to cut to the chase and have himself prematurely suspended—a premium immortality service the Convergence offers its preferred clients. Jeff sees this as the latest in a series of fatherly abdications: Their relationship is overshadowed by Ross’s abandonment, decades previously, of him and his mother.

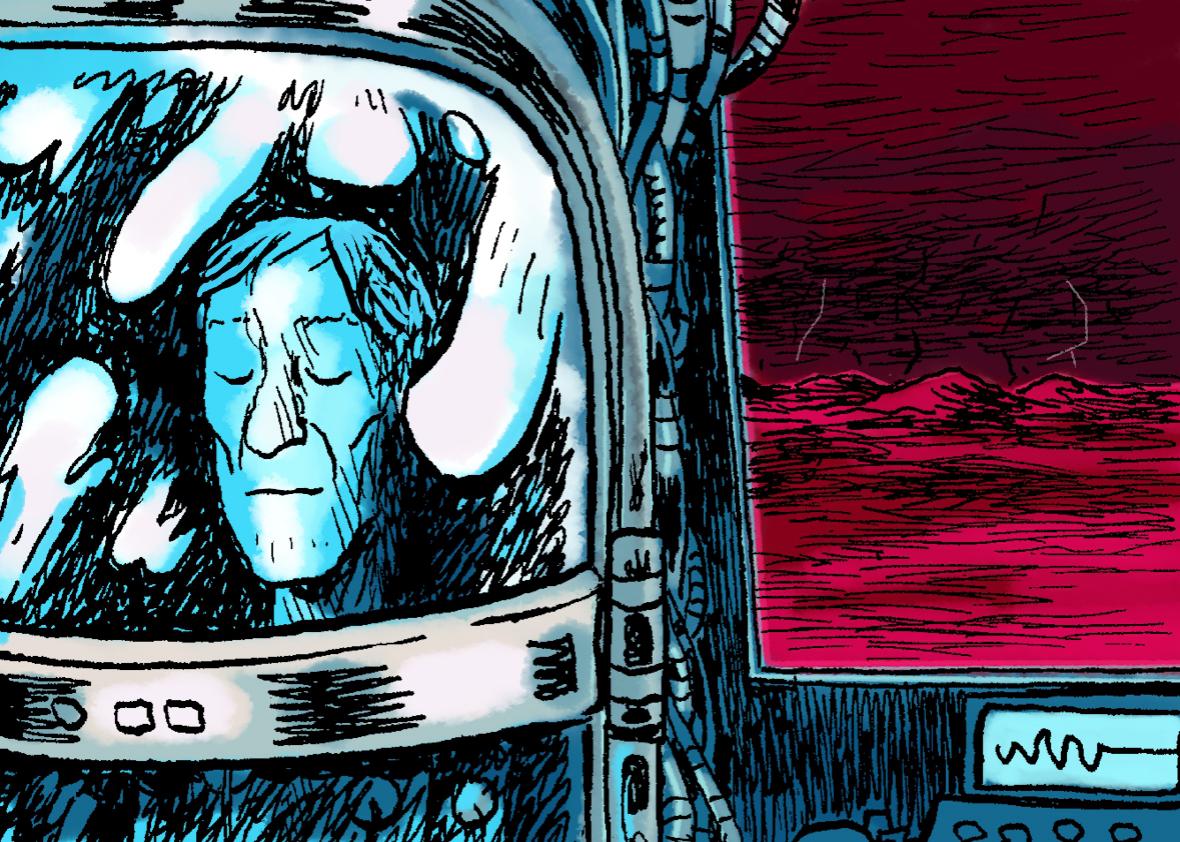

If all this makes Zero K sound like a family melodrama set against the backdrop of a techno-millenarian sect (a husband’s love! A father’s betrayal! A billionaire’s desperate quest for immortality!), let me remind you that this is a Don DeLillo novel, and so such hot-blooded novelistic concerns are little more than a backdrop to the backdrop—a means of populating the setting, of animating the theme. DeLillo’s foregrounding of backdrop frequently happens on a fairly literal level: There are several interludes in which Jeff loiters in the hallways of the Kyrgyzstan facility, gazing at a series of huge screens on which stylized silent films of cataclysm are projected: floods, tornados, self-immolating monks, terrorist atrocities. “They were drenching me in last things,” as Jeff puts it. As ever, DeLillo is clinically interested in the haunting spectacle of catastrophe on film. (In Underworld, the Zapruder footage of JFK’s assassination becomes a projection of death-haunted consciousness itself—“some crude living likeness of the mind’s own technology, the sort of death plot that runs in the mind … a model of the nights when we are intimate with our own dying.” For DeLillo, all technologies are, on some level, technologies of death.)

Jasper James/Millennium Images, UK

His artistic trajectory has taken him, thematically, further into the reaches of speculative abstraction and, stylistically, into a kind of poetics of cultural exhaustion. His preoccupations with the deceleration of narrative time and the passage of history toward some unnamable apocalyptic event have become more pronounced with every new work. In this sense, the writer he seems more and more to resemble is Samuel Beckett. Zero K exhibits unmistakable traces of Beckett’s late style—in DeLillo’s increasingly terse humor, in sentences that seem to contain their own negation. See, for instance, Ross’s description of the view of the landscape from the window of his father’s room at the compound: “Sky pale and bare, day fading in the west, if it was the west, if it was the sky.” This is the sort of sky, dead or nearly dead, you imagine Clov looking out at in Endgame and the sort of description of it he’d give.

In the novel’s short and disorienting middle section, DeLillo delivers the unmediated consciousness of Artis, the telegraphic flickerings of her brain in its purgatorial suspension between life and death.

Time. I feel it in me everywhere. But I don’t know what it is.

What I understand comes from nowhere. I don’t know what I understand until I say it.

I almost know some things. I think I am going to know things but then it does not happen.

You can imagine these words coming out of the disembodied mouth of Not I, or spoken by the self-devouring voices of the urned dead in Play.

DeLillo’s fiction has featured some irreducibly strange and indelible characters. But what has tended to be most memorable about them is the language with which DeLillo invests them, the singularity of voice. In Zero K, as with most of his more recent work, DeLillo’s characters often feel less like fully realized human beings than conduits for the various preoccupations and ideas at work in the narrative. Although it is often off-putting and compromises the sense of immersion in a compellingly ideated fictional world, this sense of incomplete realization seems structural to the book’s aims—to its portrayal of a life of overwhelming technological connectedness, in which people exist at a remove from each other and themselves. “I feel artificially myself,” Artis says on the eve of her cryonic suspension. “I’m someone who’s supposed to be me.”

The novel is saturated with a sense of lost meaning, an untethering of everything—people, places, objects—from their former significance. It has long been Jeff’s custom, he tells us, to force himself to define certain everyday terms, a gesture of desperate clutching after meaning. There is, for example, this passage near the beginning of the book, which reads like a reduction of Jacques Derrida to deadpan shtick:

Once, when they were still married, my father called my mother a fishwife. This may have been a joke but it sent me to the dictionary to look up the word. Coarse woman, a shrew. I had to look up shrew. A scold, a nag, from Old English for shrewmouse. I had to look up shrewmouse. The book sent me back to shrew, sense 1. A small insectivorous animal. I had to look up insectivorous. The book said it meant feeding on insects, from Latin insectus, for insect, plus Latin vora, for vorous. I had to look up vorous.

There’s a character who comes out of nowhere near the end of Zero K and never appears again, a leader of the Convergence who addresses a room of people about to be preserved. She’s barely a character at all, really, so much as a voice, sent to deliver a monologue to the soon-to-be-disembodied acolytes of the Convergence. DeLillo, who turns 80 this year, is extraordinarily penetrating on the ways in which our lives have been permeated and estranged by our pervasive technologies:

Haven’t you felt it? The loss of autonomy. The sense of being virtualized. The devices you use, the ones you carry everywhere, room to room, minute to minute, inescapably. Do you ever feel unfleshed? All the coded impulses you depend on to guide you. All the sensors in the room that are watching you, listening to you, tracking your habits, measuring your capabilities. All the linked data designed to incorporate you into the megadata. Is there something that makes you uneasy? Do you think about the technovirus, all systems down, global implosion? Or is it more personal? Do you feel steeped in some horrific digital panic that’s everywhere and nowhere?

DeLillo’s gaze on contemporary culture retains its unsettling intimacy, even as his writing has become more detached in affect. Reading him, the impression is of viewing the world from a great distance through an extremely powerful lens: Everything is remote but revealed with uncanny clarity. You know where you are with DeLillo. You know where you are, because you’ve been told.

—

Zero K by Don DeLillo. Scribner.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.