Freely adapted from The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture by Glen Weldon, out now from Simon and Schuster.

Let’s get one thing absolutely clear: Robin isn’t gay.

Don’t let the green Speedo and the pixie boots steer you wrong; Dick Grayson is as straight as uncooked spaghetti. In fact, there have been several Robins over the years, and not one of them has exhibited any trace of same-sex attraction or evinced anything resembling a queer self-identity.

Neither, it feels important to note here at the start, has Batman.

Don’t take my word for it. Ask anyone who’s written a Batman and Robin comic. Or, you know what, you don’t have to: Dollars to donuts they’ve already been asked that question, and have gone on record asserting the Dynamic Duo’s he-man, red-blooded, heterosexual bona fides. Batman’s co-creators, Bill Finger and Bob Kane, both firmly swatted the question down. So have writers like Frank Miller, Denny O’Neil, Alan Grant, and Devin Grayson—though Grayson admitted that she could “understand the gay readings.”

So there you have it. After all, if a character isn’t written as gay, then that character can’t possibly be gay, right? We all agree on that? Good, then we can move on to more important matters, and…

… Sorry? Was there a comment in the back?

… Yes, you, Grant Morrison, writer of several Batman comics (Arkham Asylum, JLA, Batman, Batman Inc.) over the course of the past three decades? You had something you wish to add? Something you said to Playboy magazine in 2012?

Gayness is built into Batman.

… Um.

Batman is VERY, very gay.

OK great super helpful thanks for that—

Obviously as a fictional character he’s intended to be heterosexual…

Yes! My point! THANK you. Now—

… but the whole basis of the concept is utterly gay.

I see. Well look, Grant, we really have to move on, so—

I think that’s why people like it. All these women fancy him and they all wear fetish clothes and jump around rooftops to get him. He doesn’t care—he’s more interested in hanging out with [Alfred] and [Robin].

Security? Please escort that bald, nattily dressed Glaswegian out of the hall. Sorry about that, folks.

Now, where was I …

Why Is Dick the Butt of so Many Jokes?

You’ve heard the gags, we all have. Slurs, cheap puns, and innuendo have dogged Bruce and Dick’s partnership from the moment it began in 1940. The editorially mandated addition of Robin the Boy Wonder—the first kid sidekick in comics—occurred less than one year after Batman’s debut, and it accomplished several things at once. It lightened the comic’s tone, a necessary move as the Caped Crusader was developing a reputation for murdering the bad guy; his publisher worried that parents’ groups would object. It also gave Batman—who was and remains, beneath all that bat-themed fetishist folderol, a detective in the Sherlock Holmes mode—a loyal Watson to whom he could explain his leaps of deductive reasoning. In giving Batman someone to care about, it raised the stakes. Most importantly, perhaps, it doubled the comic’s sales.

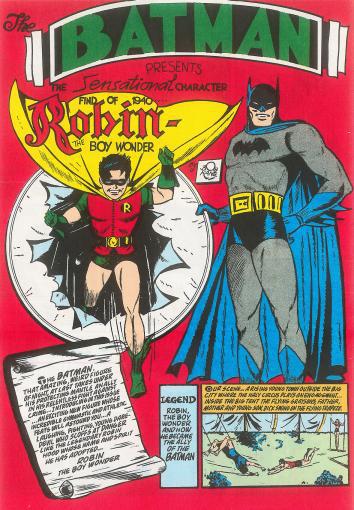

But gay subtext managed to insinuate itself into the Dynamic Duo’s dyad from the very start. The opening page of Robin’s debut story in the April 1940 issue of Detective Comics No. 38 featured an introductory scroll jammed with breathless declamatory copy about “THE SENSATIONAL CHARACTER FIND OF 1940 … ROBIN, THE BOY WONDER!”

It began, “The Batman, that weird figure of the night, takes under his protecting mantle an ally in his relentless fight against crime …”

DC Comics

Or at least, that’s how it was supposed to begin.

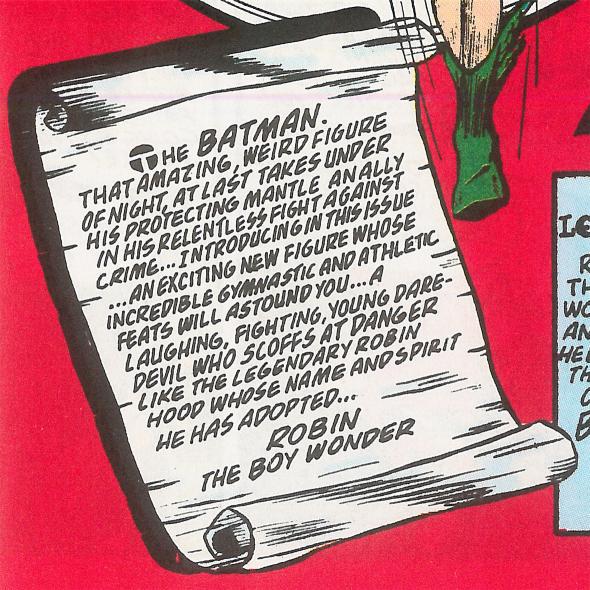

But the page’s letterer, tasked with squeezing a hell of a lot of text onto said scroll, unwittingly shoved the words “an” and “ally” so closely together as to effectively elide the space between them.

Thus, the first thing readers ever learned about THE SENSATIONAL CHARACTER FIND OF 1940 was that he was someone whom Batman “took under his protecting mantle anally …”

DC Comics

So there it was, instantly coded into the poor kid’s narrative DNA. Maybe it was fate, then. Maybe everything that came after was unavoidable.

“A Cold Shower, a Big Breakfast!”

True, their partnership came factory-installed with unintended meta-meanings that read to us today like coyly coded messages. Later in that very first Robin story, for example, after young circus acrobat Dick Grayson’s parents are murdered by the mob, Batman swoops down upon the shaken youngster and matter-of-factly informs him, “I’m going to hide you in my home for a while.”

DC Comics

Thus young Dick became Bruce Wayne’s ward, and many stories in the ’40s and ’50s began by depicting the man and boy engaged together in some leisure-time pursuit. Again and again, however, said tableaux stubbornly bore a romantic, lavender-scented shading.

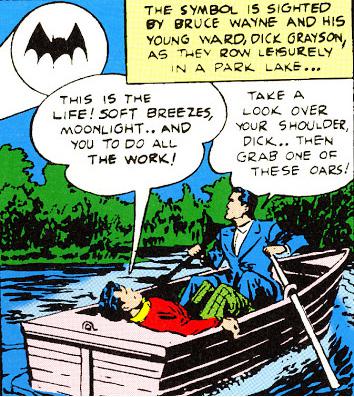

Take 1942’s Batman No. 13, which saw Bruce and Dick Owl-and-Pussycatting it up in a rowboat on a pond in a Gotham City park. Just the two of them. At night.

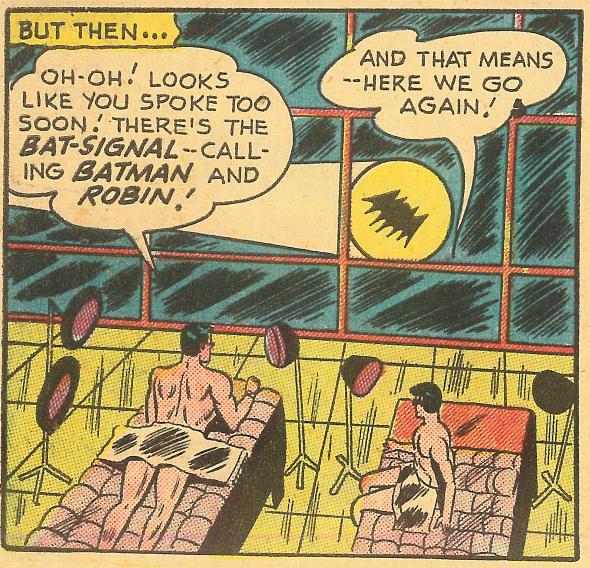

Or the panel of World’s Finest No. 59 from 1952, in which naked Bruce and Dick lie next to one another, languidly bronzing their brawny physiques under matching sun lamps.

DC Comics

And of course there were the plots, many of which turned on Robin’s seething jealousy over Batman’s romantic interests and his paranoia that he might get replaced at Batman’s side by some rival crimefighter. In this era, elaborate ruses and misdirection were the twin engines of comic book storytelling, which meant many a comic began with Batman performatively rejecting Robin as his partner, an act that would send the tearful lad to his sumptuously appointed bedroom to (choke!) and (sob!) his guts out.

People noticed. One person, in particular: Dr. Fredric Wertham, a psychiatrist convinced that comic books were directly responsible for the scourge of juvenile delinquency, led a nationwide anti-comics crusade that proved hugely effective. He published his “research” (read: testimonials from his juvenile psychiatric patients strung together with anti-comics rhetoric) in a book called Seduction of the Innocent in the spring of 1954, just as he testified before Sen. Estes Kefauver’s Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency.

Wertham devoted a scant four pages of his book to Batman and Robin; he had bigger fish to fry, attacking the luridly violent, sexist, and racist imagery found in many crime comics of the day. (About which: Dude had a point.) He did call Superman out as a fascist, and he noted that Wonder Woman’s whole shtick seemed unapologetically Sapphic. When it came to the Dynamic Duo, he seemed to relish drawing the reader’s attention to Wayne Manor’s “beautiful flowers in large vases” and the fact that Bruce was given to swanning about the estate in a dressing gown.

“It is like a wish-dream,” he famously wrote, “of two homosexuals living together.”

Fred Wertham, people. Surely one of history’s first ’shippers.

Even as Wertham was preparing to make his case on national television, the makers of the Batman comic unwittingly served him up fresh fodder. Batman No. 84 hit newsstands in April 1954, during Wertham’s Senate testimony. Its story “Ten Nights of Fear” begins with one of the most infamous panels in Batman’s 77-year history: Bruce and Dick waking up in bed together.

DC Comics

“Morning,” reads the narration. “And it begins like any other routine morning in the lives of millionaire Bruce Wayne and his ward, Dick Grayson …” We are thus explicitly told that this sharing of Bruce’s bed is common Bat-practice.

“C’mon Dick!” says Bruce, yawning. “A cold shower, a big breakfast!”

History does not record Dr. Wertham’s reaction to receiving such an exquisitely formed distillation of his argument at such a propitious moment. But I think “a cold, humorless smile” is a safe bet.

Now, of course taking comics panels out of context like this is silly. After all, Bruce and Dick’s relationship was essentially that of father and son, and kids crawl into bed with their parents all the time.

This is the issue with gay readings. Any given bond between males can be homosocial without being homoerotic, and even the most explicitly homoerotic bond can exist without ever rubbing up against homosexual desire. To willfully and sneeringly misinterpret what was clearly intended as a familial connection as a romantic one—as Wertham did in 1954 and as so many Tumblr feeds do today— seems ungenerous at best and snide at worst, no?

As I write in my new history of Batman and nerd culture, The Caped Crusade: No! Intention doesn’t matter when it comes to gay subtext. Imagery does.

Remember: Queer readers didn’t see any vestige of themselves represented in the mass media of this era, let alone its comic books. And when queer audiences don’t see ourselves in a given work, we look deeper, parsing every exchange for the faintest hint of something we recognize. This is why, as a visual medium filled with silent cues like body language and background detail, superhero comics have proven a particularly fertile vector for gay readings over the years. Images can assert layers of unspoken meanings that mere words can never conjure. That panel of a be-toweled Bruce and Dick lounging together in their solarium, for example, would not carry the potent homoerotic charge it does, were the same scene simply described in boring ol’ prose.

The Shadow of Wertham

Wertham’s crusade rallied church groups, schools and local legislatures against comics. Crime and horror comics folded by the dozen. Even Superman struggled to hang on. And as for Batman and Robin, they went from comics’ premiere double act to ensemble players, welcoming a bevy of masked hangers-on into the Bat-ranks.

Alfred the butler had joined them in 1943, serving as a 24/7 chaperone. Now, between a Bat-Hound, a Batwoman, a Batgirl, a Bat-5th-Dimensional-Magical-Imp, and—all too briefly—a Bat-Ape, Batman and Robin could hardly find any time alone together. This was no coincidence. The shadow of Wertham lingered long into the ’60s, and Batman editors resolved to do what they could to dispel it, even if doing so came with a body count: When asked why Alfred the butler was killed off—briefly—in 1964 to be replaced by the dithering Aunt Harriet, editor Julius Schwartz averred, “There was a lot of discussion in those days about three males living in Wayne Manor.”

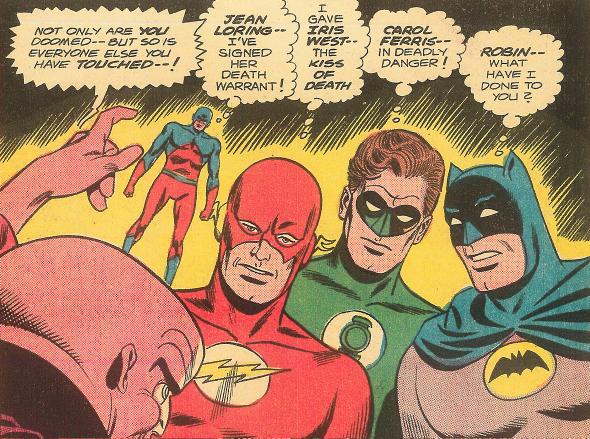

But gay subtext, like information, longs to be free, and the universe doggedly conspired to keep dropping inadvertently hilarious panels like this one, from a 1966 Justice League of America comic, into Bat-canon:

DC Comics

When the 1966 television series Batman came along it transposed the Dynamic Duo of that era’s comics—a pair of sunlit, anodyne, civic-minded cops in capes, essentially—onto the screen but imbued the proceedings with a deadly mock-seriousness that made it a cultural phenomenon. Although the show became inextricably associated with the notion of camp, its pop-art sensibility never came off as particularly gay despite the presence of guest villains played by such fierce divas as Tallulah Bankhead and Liberace.

After the show went off the air, the creators of Batman comics resolved to get out from under its inescapable cultural penetrance by rebooting Batman as a lone avenger of the night. They shuffled Dick Grayson off to college in 1970, effectively ending the Bruce–Dick partnership that had grown so weighted with gay meta-meanings over the decades. Which, really, was all it took for heteronormativity to reassert itself, because while separately Batman and Robin came hardwired with vague gay associations (the fear of one’s secret identity being exposed, for example), it was only ever their status as a bonded male–male pair that had truly raised eyebrows.

Once out of Bruce’s shadow, Dick dutifully dated women and started his own superteam. Eventually he cast off the Robin identity for good, adopting the totally butch-badass nom de spandex Nightwing.

DC Comics

Read more in Slate:

- Why Supergirl Is a Better Superman Story Than Batman v Superman

- Sad Ben Affleck, Like Batman, Has Seen the Future and Doesn’t Like What It Holds

- Dear Hollywood, Stop Stealing All Your Ideas From Frank Miller

As for Batman, he cycled through a number of replacement Robins; he’s like that friend who keeps dating slightly different iterations of the guy who got away in college. In recent decades, it certainly seems as if his writers have grown more self-aware about unintended gay readings and hence more circumspect. Batman has self-policed himself, and his optics, much more thoroughly since Dick left; it’s quite rare to see any subtextual gay elements bubbling up to the surface.

But when they do, those bubbles geyser up at a furious froth with enough pounds per square inch to blow the Dynamic Duo’s closet door off its hinges. The primary case in point: the Joel Schumacher films Batman Forever (1995) and Batman & Robin (1997).

Under Schumacher’s direction, both films out-and-proudly featured a sugar-daddy Bruce and a surly, tank-topped, rough-trade Dick, complete with earring. And motorcycle. And Lysistrata-like rubber codpiece. And, of course—say it soft and it’s almost like praying—Bat-nipples.

In the comics, Bruce and Dick had long before gone their separate ways. But here, on Schumacher’s garish, neon-lit movie screens, they were together again. The films proved a final, defiantly queer victory lap for the Bruce and Dick team. What Schumacher produced wasn’t gay subtext; it was gay domtext.

Yes, these two movies were gloriously godawful trainwrecks. No human being capable of rational thought would dispute that. But while the Schumacher Bat-films seem like outliers among the kinds of Batman stories that reign in the present day, they fit squarely within a long and storied legacy of homosocial, homoerotic, and homosexual resonances in the Bruce–Dick partnership.

Gayness is built into Batman.

Schumacher knew this. When he looked at Batman, Schumacher saw him in much the same way that thousands of queer readers had seen him for decades. He knew something about Bruce that Bruce will never be permitted to admit to himself, and he put it onscreen. And in much the same way, when Schumacher looked at Robin, he knew something important—something central, and revelatory, and eternal—about Dick.

—