Novels about India tend to mimic their subject. For one, they’re sprawling. That started, most likely, with Salman Rushdie, who in 1981 published the very sprawling Midnight’s Children. Since then, several authors—Vikram Seth, Arundhati Roy, Rohinton Mistry, Jhumpa Lahiri—have written their own jumbo tableaux: dense, overripe books that teem, like India, with color and sound and conflict. Reading this fiction is absorbing, simply because there’s so much to absorb; its sheer muchness is meant to capture the country writ large.

The approach is well-intentioned. As a place and as an idea, India pleads for context, for order imposed on the many cultures and contradictions tangled within its borders. But as the writer Amit Chaudhuri once argued, there’s something off about the notion that, “since India is a huge baggy monster, the novels that accommodate it have to be baggy monsters as well.” In the same essay, Chaudhuri claimed it was time for the “postmodernist Indian English novel” to reject “a mimesis of form, where the largeness of the book allegorizes the largeness of the country it represents.” His point endures. Despite its pretense of panorama, the mimetic impulse has a blinkered, domesticating aspect. It produces bear-hug fiction, books that gather all complexities in a tight, inclusive embrace, to often suffocating effect. These books about the subcontinent often assume that a tidy, post-colonial totality called India even exists. They try, in short, to make coherent what is not.

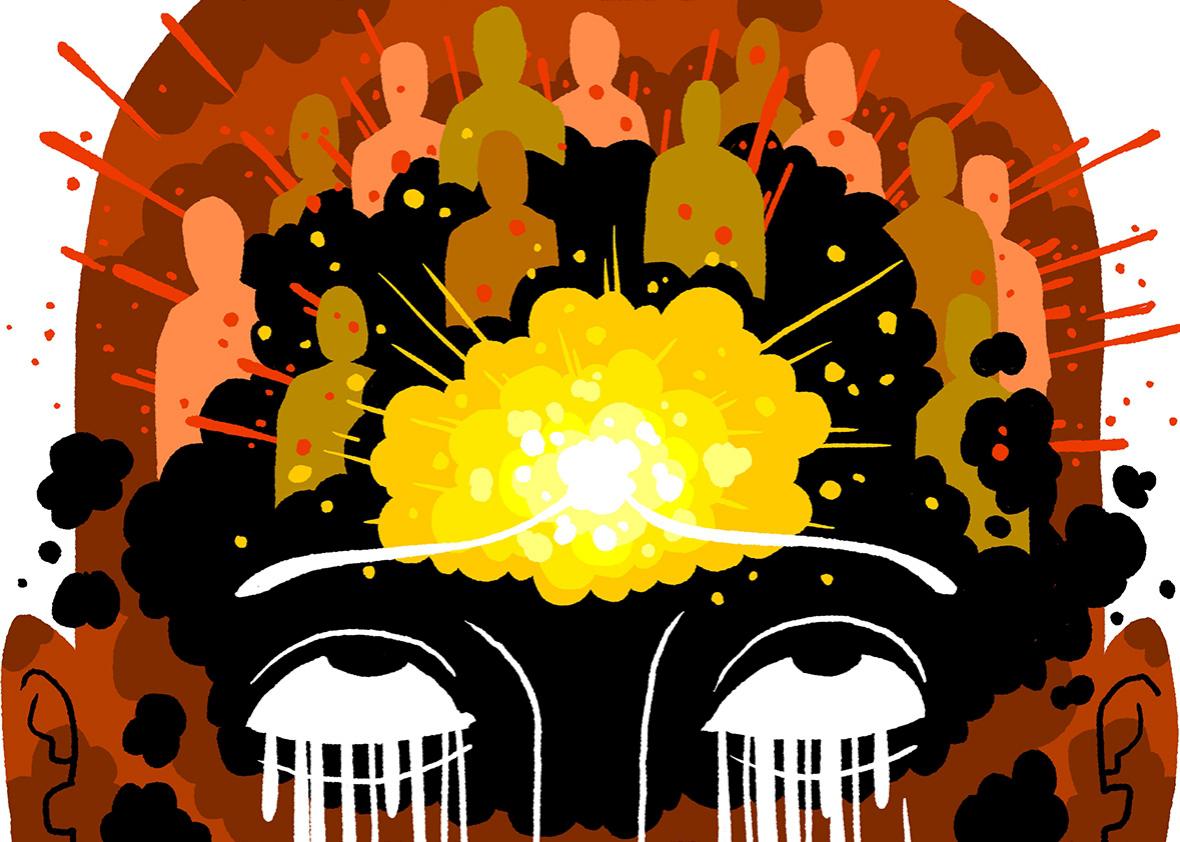

Karan Mahajan’s deeply affecting second novel, The Association of Small Bombs, is in many ways a screed against coherence. Though it bears glancing resemblance to its baggy-monster precursors—it spans 30 years and three countries, and winds around two families and many more protagonists—it is in fact a keenly inward work, averse to forced parallels. It attempts no ennobling linkage of different forms of suffering, of this character’s plight and that character’s purpose. Some writers are quick to weave common threads; Mahajan delights in letting them fray. His book’s project is not connection but its erosion, and, accordingly, his approach isn’t rote panorama so much as an extended, off-kilter orbit of the void.

The void in question is a bomb. In 1996, Vikas and Deepa Khurana lose their two sons, Tushar and Nakul, to a blast in Lajpat Nagar, one of the many bustling shopping markets that dot Delhi. The attack kills 13 and injures 30. The boys’ best friend, Mansoor Ahmed, is with them at the time, but survives, stumbling home and into the arms of his parents, wealthy Muslims ensconced in a mansion in South Ex. This all happens in the first 20 pages; the rest of the book is a study in aftershock. The Khuranas cope, badly, with death—they have a daughter and proceed to ignore her; their marriage halts and heals and halts again—while the Ahmeds endure the trauma of survival, Mansoor’s life no more blessed for being spared. Elsewhere, we follow Shaukat “Shockie” Guru, the career terrorist who planted the bomb, and Ayub, a sage young villager who schools Mansoor in the art of nonviolent activism.

If you’ve had even a cursory encounter with art about Indians, many of these beats are familiar. There’s the jig across different countries and generations; the son (Mansoor) venturing to America; the dutiful nods to Hindu-Muslim tensions. (Thankfully, no wedding is involved.) Usually these tropes are imbued with plodding lessons about multiculturalism, or lacquered with a coat of tropical detail. Mahajan, though, is the furthest thing from didactic, and his tone is too biting for exoticism. (Rare are the spurts of untranslated Hindi that, in other works, feel like forced bona fides.) When he describes Delhi, he does so with a warm, spiky familiarity that never veers into sentiment, noting the “stink of racing petrol,” the “alien bubbles of motorcycle helmets,” and the ritual of “coffee and biscuits and fizzing lime soda” in the late afternoons. Especially lovely is when his observation transmutes into epigrammatic insight: “In a great city, what happens in one part never perplexes the other parts.” Or: “In Delhi, there are no bird-watchers, only machine-listeners.”

The closest the book comes to Rushdie’s magical realism, to that mode of sublimated spirituality that typifies so much of the canon, is when it takes somber turns into prophecy. The text is riddled with clairvoyant asides, in which Mahajan lifts the curtain of the plot and reveals a character’s fate. Very often, those characters exhibit a similar sense of futility about their actions: “It’s already happened,” one protagonist tells himself before planting a bomb. “It’s long over. When I get to the market, I’ll discover it’s on fire and it’ll be as if I wasn’t even present for what I did.” This would usually scan as a study in apologia, a bracing example of how a terrorist might confront the horror of his own actions. But Mahajan has bigger targets in mind. He later indicts the entire country: “But Indians were like that, happy to be puppets of fate. ‘Chalta hai.’ ‘It’s in God’s hands.’ ‘Everything goes.’ ”

All this foreshadowing and chatter about fate doesn’t short-circuit the book’s suspense, because its primary theme is the flattening of time. “A good bombing,” we’re told in the opening pages, “begins everywhere at once,” and in the same way Mahajan locates his narrative not in the passing of months and years but in the formative, all-encompassing moment. Hence the inciting explosion, one of many liquid inflection points at which circumstance becomes feeling becomes fate. After his sons’ death, Vikas, a documentary filmmaker, obsesses over a new project:

The thing was, he didn’t want to make a film about the aftermath; he was living the aftermath. No—he wanted to make a film about the moment itself, when there was a hush as the bomb shut off humans and machines in the vicinity and then viciously rearranged everything. Yes, he wanted to film the moment itself, slow it down open it up like a flower over time, like the ultraviolent bomb dreams that filled his nights.

Molly Winters

It’s a futile pursuit, of course. A bomb erases the moment; it turns time, for a brief instant, into a blip of banality. Mansoor often thinks about this: “His mind whipped back to the bomb, the meaninglessness of it.” When he tries to recall the explosion, he remembers only his dazed walk home, or the second, amid the heat and noise, when he spied “through a woman’s ripped kurta” his first breast. (Mahajan has an impish eye for subversion.) These characters are circling a nonentity; after fulfilling its one, obliterating purpose, a bomb is infuriatingly absent in the continued existence of its victims. The idea of it, then, becomes a surrogate force, one that animates their every move.

In flitting between the perspectives of terrorists and victims, parents and children, Hindus and Muslims, Mahajan has committed to a radical and extended act of empathy, and with that act comes the danger of abstracting the narrative into oblivion. Rote relativism supplies many perspectives but little insight. One of the ways in which Mahajan grounds his compassion, and gives it a moral compass, is by paying immense attention to the corpus: The book is relentlessly physical, a running catalog of tics, gestures, and carnal afflictions. We return, many times, to the bodies of Tushar and Nakul, splayed in silence. Deepa’s depression manifests in her light, thin-boned hands, “cold and fragrant with Nivea cream.” Abusive cops cripple Malik, the meek propagandist, and DIY explosives tatter Shockie’s palms. Long, aching passages detail the pain in Mansoor’s wrists, and when he goes to college in California, a few months before 9/11, he’s shattered not by anti-Muslim sentiment but by an even more American perversion: porn. The blame is always in the body. And as Mansoor notes:

The body itself was abhorrent. It could be made subservient to anything. It could work for despots, tyrants, fascists, terrorists—it could work for machines. He realized the pointlessness, at a time like this, of having a mind.

Ideology, culture, countries—these things fade as meat and muscle are threatened, and throughout the book characters discover just how much their mental state pivots on bodily preservation. Where other authors concede the clash between the West’s physicality and the East’s spiritualism, Mahajan deftly shows how fundamentally reliant each is on the other, and, consequently, how silly the binary truly is. The men who make bombs, after all, almost uniformly believe that their sacred purpose must be achieved through the body—through limbs bloodied, heads smashed, and sons slaughtered. Terror? It’s nothing but the moment when fear finds flesh.

–

The Association of Small Bombs by Karan Mahajan. Viking.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.