Nelle Harper Lee scoffed at her National Treasure status. She really didn’t care to be a local attraction either. The souvenir shop at the Alabama courthouse she put on the map drove her crazy. “It’s not like they’re selling To Kill a Mockingbird sugared breakfast cereal,” I reminded her on occasion, and what else did Monroeville have going for it since the Vanity Fair plant closed? Once she responded, perverse, mirthful, and oracular: “Yes, I’m the local Jesus. I save everybody.”

Lee was more like the National Antidote—probably she would have preferred emetic, or gag reflex, something that expressed her unwillingness to humor the Chamber of Commerce or our contemporary age of ubiquity and oversaturation. Those TKAM T-shirts notwithstanding, she was the anti-brand, a world-famous media shunner who remained relevant after producing one true thing 56 years ago. Mockingbird, as she called her deathless 1960 novel, is not simply about the moralizing turbo of childhood imagination, but induces in the reader that endless, expectant feeling of the hot summer day, a sense that anything can happen but usually doesn’t—you know, Boo Radley doesn’t come out of the house.

Until he does, big time. In the final year of her life, Lee, who died at 89 in February, ended half a century of literary seclusion and shocked the world with a “sequel,” Go Set a Watchman, reportedly written before Mockingbird and rejected by her publisher. “ET TU, ATTICUS?” the Huffington Post’s lead story proclaimed the return of Atticus Finch. (If Nelle saw the page, she undoubtedly blurted the correct, vocative case of Atticus.) The last moral white man standing in Depression-era Mockingbird was now a pillar of the White Citizens Council circa 1956, the Ku Klux Klan in coat and tie. Lee’s was indeed a stunning departure, and like Boo’s ultimate appearance in Mockingbird—both life-saving and death-dealing—it has forced us to examine what “moral” means. Does Watchman cast doubt on whether Mockingbird was trustworthy after all, or has it propelled us toward a higher truth? And what insight does it give us into Lee’s own shuttered universe? I was her friend; yet she was more a mystery than I knew.

Even pre-Watchman, though, Atticus had been losing a bit of his shine. A former Alabama governor, Albert Brewer, who had acquired some Atticus-like mystique as the anti-George Wallace, told me a decade ago that his law students didn’t get Atticus’s appeal—he hadn’t won his case! They couldn’t see that his unrewarded persistence was the whole point. His defense of black Tom Robinson against white Mayella Ewell’s false charges of rape stood as the pure example of moral courage because of foregone failure as well as community disapproval, not to mention the endangerment of his children.

Now more than five decades after Harper Lee first awakened so many (white) people to their moral potential, we still need to be told that black lives matter. And Lee has left us with a stinging admonishment that a fictional white man’s act of quixotic futility really doesn’t.

* * *

So was Atticus ever “legit”? It should be said that no one is as upset about the new Atticus as his daughter Scout, the author’s child-proxy in Mockingbird and Watchman’s 26-year-old Jean Louise, whose gnashing struggles to reconcile him with the father she revered compose the novel’s less than satisfying coming-of-age arc. In a conversation about Mockingbird’s evolution years ago, Nelle told me she had originally written two chapters in a contemporary setting and two in the past: “I just felt that what I had to say could best be said in that flashback.” Certainly the racial shibboleths (“Gertrude, I tell you there’s nothing more distracting than a sulky darky.”) are more effective reported at face value by young Scout than filtered through the offended ears of adult Jean Louise. But on historical consideration, I think Lee’s only option for making Atticus both plausible and morally instructive was to place him in the 1930s under a child’s gaze. Not even the liberals back then were advocating the end of segregation—only a kinder version—and it was possible to do the right thing, including represent “pet Negroes” and “poor devils,” without undermining the whole system. Though defeated for re-election, the North Alabama judge who in 1933 asserted the innocence of the Scottsboro Boys, black youths wrongly convicted of raping two white women, was endorsed by his hometown’s “power structure”—just as Atticus is defended by Maycomb’s racist newspaper editor.

The defect in Mockingbird-era liberal thinking was the belief that reform could be dictated from on high with the “good white people” in charge of the pace and manner of change, and race mentioned hardly at all. So in Watchman 20 years later, the paternalistic Atticus willing to mete out justice on his terms has been radicalized (or moderate-ized in context) by the black race’s insistence on managing its own liberation. The novel makes knowing reference to the social revolution underway in the Alabama of 1956: “that Montgomery crowd” boycotting the buses (their leader, Martin Luther King Jr., is unnamed) and a young black woman (Autherine Lucy, also generic) making a riot-thwarted attempt to desegregate the University of Alabama. Once the avatar of Socratic reason, Atticus is now infected by the state-of-war emotionalism of massive white resistance ignited by the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision—regarded in Watchman’s Maycomb as the NAACP’s “overthrow of the South.”

No wonder Harper Lee concluded that the best antidote to the groupthink of her then-contemporary South was the urgency of the individual conscience. Appearing in 1960 amid what would be apartheid’s last stand, Mockingbird’s Atticus was a rebuke to the good people: You are not off the hook just because you are paralyzed by social realities. Easier written than done, as Lee knew when she conceived Mockingbird. That she was achingly aware of her hero’s fallibility lends deeper nuance to my favorite TKAM passages, the Atticus speeches that always struck me as the author’s own retort to his soothing bromides about climbing into someone else’s skin. After Tom Robinson’s conviction, when Aunt Alexandra chides her brother Atticus for allowing the children into the trial, he responds with uncharacteristic brusqueness, “This is their home, sister. We’ve made it this way for them, they might as well learn to cope with it.” Later he tells his Scout and her brother, Jem, “Don’t fool yourselves—it’s all adding up and one of these days we’re going to pay the bill for it. I hope it’s not in you children’s time.”

I had taken Atticus’s fatalism to be brutal truth-telling. But in light of what we now know, thanks to Watchman, is coming, maybe Lee intended it to be more of an abdication.

***

Atticus worship was always an example of the human tendency to venerate deserving prophets only in retrospect, and then claim them as representatives of our True Selves rather than what they were in their time, heretics if not martyrs. And after the initial shock over our hero’s feet of red Alabama clay, the next stage of Mockingbird fan-grief was to “normalize” the new Atticus, pointing out that he wasn’t evil, just typical—or that for him to have been less of a bigot in that time and place would have abused the limits of literary license. But in fact, Atticus is worse than was necessary for historical credibility. Lee could have stopped short of making him a true-believing member of the Citizens Council’s board of directors—unconscionable, given that a lawyer of his stripe would have felt little practical fallout from desegregation. That his actions spring from tribal pique rather than principle is driven home by his arch indignation toward the NAACP lawyers—in real life, colleagues of the future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall—who are pursuing a non-authorized form of justice on his turf as peers. His observation that “the Negroes down here are still in their childhood as a people” is less a complaint than an expression of how the white South liked “their colored folk.”

Atticus’s words in Watchman will ring authentic to anyone who lived in the South under segregation. The mystery is how the Mockingbird Atticus was reverse-engineered from raw material that suggests how livid the author must have been at her own father. I saw Nelle only once post-Watchman and arrived at her assisted living facility in Monroeville prepared to ask, “So, uh, Nelle, as Atticus became more and more idolized over the decades, did you ever think to yourself, ‘Gee, I hope that manuscript doesn’t turn up and burst a lot of bubbles?’ ” Actually, it wouldn’t have gone quite like that, since by then her hearing was so bad that the visitor’s end of a conversation consisted mostly of messages written in Magic Marker. A toothache that August day last year prevented her from any meaningful interaction, and even under better circumstances, mine was the kind of “Golly gosh!” question that might have elicited an outburst of “Idiot!” or “Idiot child!”—affectionate Mrs. Dubose–isms that also ensued when one failed to identify the source of a Shakespeare quotation or insisted on escorting her to her New York apartment door after an especially fun brunch.

But I found a clue in the notes I took on that conversation nine years earlier about her decision to set Mockingbird in the past. We were having iced coffee after going to a Goya exhibit at the Frick in New York, and I had asked her if those discarded contemporary chapters had a civil rights theme. I never worried that much about treading into “sore subject” land with her, but if I pressed her too specifically on some fact she might exclaim in mock umbrage, “You are not my biographer!” So I hadn’t followed up on her vague reply—that not much “overt” was happening at the time she was writing in the 1950s, but “it was brewing.” After her death, I reread my recollections of that day, recorded a few hours later. (I did have enough sense not to pull out a pen in her presence.) One detail jumped out at me, significant enough to have snagged my memory without my understanding why: Before answering me, she had hesitated. She knew exactly what whirlwind was “brewing” in those pages. But apparently she was not yet ready to out Atticus. What made her finally do it?

Though I have no doubt that Lee was competent to OK Watchman’s publication, her literary legacy does not seem to have been her paramount concern, or surely she would have reread the manuscript before making up her mind. That she didn’t, reportedly, is one of the backhanded gifts of this publishing “twist”—leaving Watchman an in-the-clear historical artifact in which our heroine’s own sentimental attachment to “states’ rights” suggests why it was such a challenge to envision an enlightened path for Atticus. The authorial reputation might have been better served if the publisher had refrained from marketing Watchman as “an unforgettable novel of wisdom,” etc., or had at least provided some contextualizing note. But that might have been a tall order.

According to literary legend, Tay Hohoff, an editor at Lippincott, coaxed Lee’s masterpiece out of an unsatisfactory first try. But Watchman does not at all resemble the preliminary version Hohoff describes in an official company history as a “series of anecdotes.” Not that Hohoff was wrong to reject the manuscript. As Lee acknowledged in a recently auctioned letter written in 1990, now being cited for its prescient Trump-trashing, “It seems that one of the hardest things in the world (and especially is the case for Southerners) is to produce, in the midst of social revolution, work of lasting worth that reflects that revolution.” The major flaw of Watchman is that the reader can’t empathize with Jean Louise’s anguish over Atticus’s racism when there’s so little in the story to establish his prior heroism. Ironically, the one example she does offer, perfunctorily, is a black-on-white rape case in which he won an unprecedented acquittal. By reimagining that episode for Mockingbird, she transformed the courtroom where Atticus sat at the head table of the White Citizens Council into a landmark.

Once Mockingbird’s success established the context for the 1950s father-daughter drama and hindsight unlocked its meaning, was any thought given to revising Watchman for publication, bringing that promising—in parts brilliant—manuscript up to the standard Lee had since aced? And if not, after she stalled on the next effort, what did the continuing rebuff of her earliest vision do to her confidence? Perhaps some correspondence will turn up to tell us whether Watchman was ever revisited. But joining the festival of conjecture that has been this crepuscular publishing event, I can’t help but wonder if Hohoff’s best intentions might have shaded into a silencing.

Northern liberals tend to maintain faith in the “innate goodness of man” longer than their Southern counterparts, who notice that their loving community acts in conflict with its Christian ideals the first time they sing “Jesus Loves the Little Children” in Sunday school. Hohoff—a Brooklyn Quaker, biographer of a social activist—might well have had some categorical aversion to a morally confusing “hero” like Atticus, or else why would she offer such a fuzzy, unforthcoming account of Mockingbird’s genesis, as if there were something shameful about it? At the height of Lee’s post-Mockingbird fame, the editors of Esquire declined a piece she wrote involving segregationists who (like Atticus) hated the Ku Klux Klan, on the grounds that this was “an axiomatic impossibility.” Her exasperation with Esquire is on the record. Can similar disaffection be read into the terse statement she released in 2015—“I was a first-time writer, so I did as I was told”—to explain why she abandoned her original storyline? In that 1990 letter, she refers to her “old editor (known to the trade as the Quaker Hitler),” noting, “I couldn’t argue with her (nobody ever dared).”

Like the South, as well as the human race, To Kill a Mockingbird is filled with axiomatic impossibilities, beginning with Scout herself, the naïve-girl narrator with the gimlet eye of a ruthless adult. And now we have the most unbelievable notion of all: Atticus Finch, enemy of the civil rights movement. If part of Lee’s original artistic impulse had been to shame her region over its wicked ways, she eventually found her prophetic voice by substituting a model of morality for a brute attack on immorality. In other words, by becoming Atticus-like. Lee had to behave like the grown-up she so frantically wants her father to be in Watchman, and in finding that maturity, she became as mythic as her creation—the local Jesus!

Nelle once told me that her decision to spurn celebrity and lie low hadn’t been an abrupt choice but happened over time when she began to realize that she “had written the kind of novel that made readers want to meet the author. Do John Updike’s readers feel like they have to meet him?” Of course, I had once been one of the acolytes she was ducking, having developed my Scout complex even before reading the book: My small fifth-grade class at the Brooke Hill School for Girls had been invited to the movie’s premiere in Birmingham because our classmate Mary Badham starred in the film as Scout.

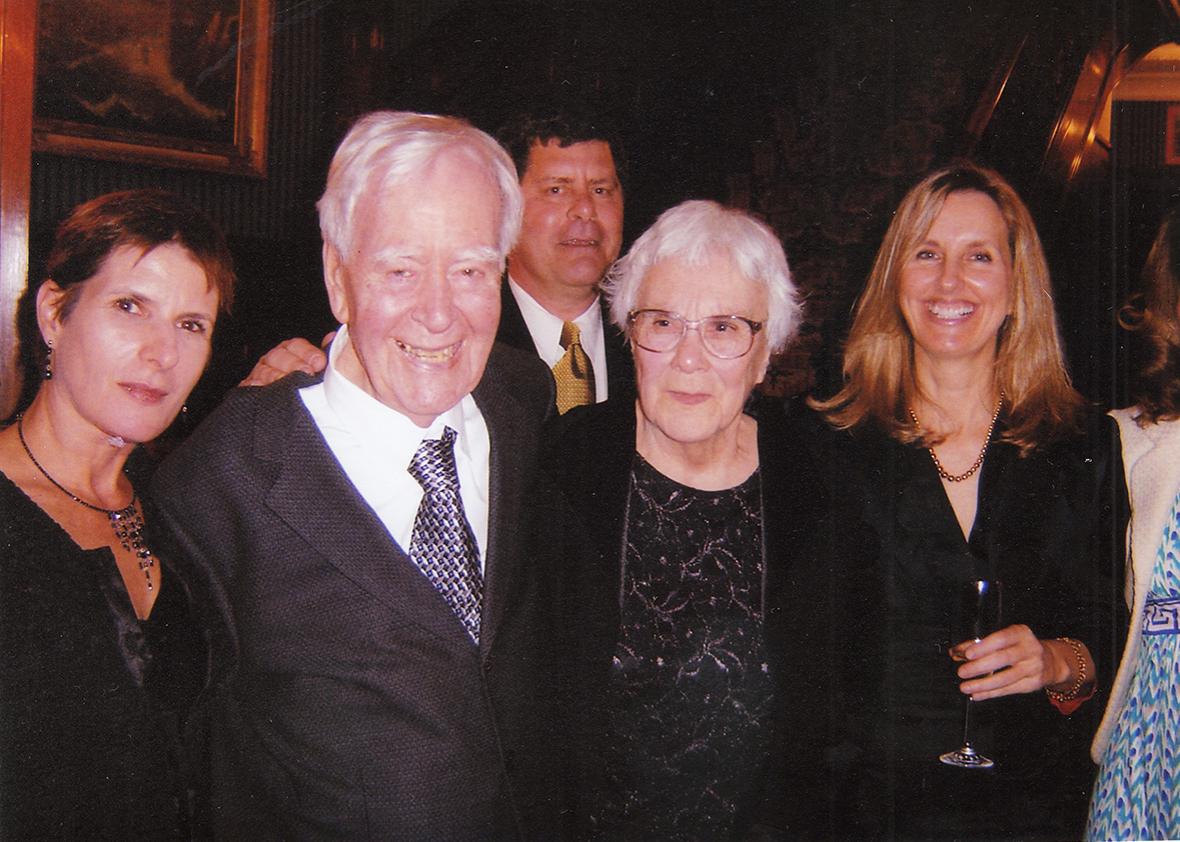

My friendship with the real Scout began 12 years ago, when we were ex-pat writers in New York reflecting back to each other the awe of our strange and common home place. Reading the first line of Watchman, about Jean Louise on the last leg of her trip home from New York, had made the hair on my forearm do the wave: “Since Atlanta, she had looked out the dining-car window with a delight almost physical.” Through many drafts, my own (nonfiction) book about going back to Alabama to contend with a racist father had opened almost identically, except that my “unreasonable happiness” surged on an airplane out of Atlanta instead of a train and was triggered by the Proustian aroma of Juicy Fruit gum being unwrapped, as if the passengers were signaling, Finally, we can be ourselves! It turns out Nelle had been way ahead of us all on the perpetual journey home, that delightful, heartbreaking project of confronting ourselves: best achieved by discovering our better angels, she demonstrated, then recognizing that they, too, are mortal.

—

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.