In early March, Louisiana State University announced that Ben Simmons, a 6-foot-10-inch Australian freshman who’d led the Tigers in points, rebounds, assists, steals, and blocks, was academically ineligible for the Wooden Award, college basketball’s most prestigious individual honor. Failing to meet the award’s minimum GPA of 2.0 is an impressive display of scholarly indifference, but Simmons shrugged off his disqualification, telling a reporter: “They talk about playing so much then they bring other stuff into it. It is what it is. I’m not fazed by it.”

“Not fazed” is the correct response. Since arriving in Baton Rouge, Simmons’ status as a college student has been a purely theoretical formality for everyone but the LSU faithful. Simmons has been a consensus top pick in the 2016 NBA Draft since before the season began and would likely have been a top pick in the 2015 draft as well, had that been an option. But like every high school basketball phenom in the past 10 years, Simmons was barred from entering the league until he was 19 years old and one year removed from his high school graduating class. Simmons’ rather undistinguished academic career is a byproduct of the NBA’s age limit, controversially instituted in 2006 to stop a decadelong deluge of newly minted high school graduates seeking to enter the world’s top basketball league.

That deluge is the subject of Jonathan Abrams’ riveting new book, Boys Among Men: How the Prep-to-Pro Generation Redefined the NBA and Sparked a Basketball Revolution. Abrams sets out to tell the story of the avant-garde of high school talent that infiltrated the NBA from 1995 to 2005, transforming the sport of professional basketball in the process. By the time the age limit was finally instituted, anyone looking to field a starting fantasy five of prep-to-pros could draft Dwight Howard, Kevin Garnett, Tracy McGrady, Kobe Bryant, and LeBron James (playing out of position at the point, for neither the first nor the last time).

Abrams is best known as one of the brightest talents at Bill Simmons’ late, lamented Grantland, where he built a reputation as a journalist with a nose for the most interesting story and a voice for telling it in the most interesting way. During his time at Grantland Abrams effectively mastered two niches: The first being the oral history of some cultish basketball happening and the second being the lengthy profile of a quirky, under-the-radar player with an unexpectedly fascinating life story.

Nicola Borland

Boys Among Men often feels like a combination of these two forms, an exhaustive work of research and reporting that reads with the propulsive energy of a magazine feature that makes you late for something important. Abrams’ narrative takes as its central protagonists the prep-to-pro generations’ dual Moses figures, Kevin Garnett and Kobe Bryant. Before Garnett entered the league out of Chicago’s Farragut Career Academy in 1995, it had been 20 years since a player had jumped directly from high school to the NBA. Prior to that year’s draft Sports Illustrated put a baby-faced Garnett on its cover, along with a foreboding “Ready or Not…” headline. Garnett was picked fifth overall by the Minnesota Timberwolves; the following year Bryant was drafted 13th overall, out of Lower Merion High School in the Philadelphia suburbs.

On the surface the two cases couldn’t have been more different. Garnett’s pioneering prep-to-pro leap was made out of necessity by a lean and hungry prodigy from an impoverished family background who’d failed to obtain the necessary test scores to play in the NCAA as a freshman. Bryant, on the other hand, came from comfort and affluence, the son of a pro basketball player who likely could have attended any college program he desired and who jumped to the NBA purely out of personal ambition. (Abrams’ book reports that Bryant, then a high school junior, was irritated by Garnett’s decision to enter the draft, because Kobe, always the competitor, had aimed to be the first of his generation to make the jump.)

The most significant story that pulses underneath the many taut yarns of Boys Among Men is one of labor. This was a decade in which elite college-age black male athletes—a population that, in terms of value versus compensation, ranks among the most unfairly treated labor pools in modern American society—found a loophole in the Byzantine rules designed to exploit them and worked it until the NBA sewed it closed (no doubt to the delight of the NCAA, which had suddenly lost its lucrative grip on the country’s top amateur talent). It might be odd to think back on Garnett and Bryant—long-in-the-tooth legends who’ve each made hundreds of millions of dollars before turning 40—as youthful labor revolutionaries, but that’s what they were.

Abrams is a fantastic storyteller, and Boys Among Men unfolds with a broadly chronological structure but with a natural sense for the well-timed digression. For instance, the professional success of Amar’e Stoudemire, who prior to entering the league had been the subject of unflattering coverage ranging from investigations of AAU corruption to humiliating dissections of his family background, stands as one of the great rebukes to anti-prep moralism. Abrams wraps Stoudemire’s tale into a sort of sidebar chapter about the man who drafted him: Suns General Manager Jerry Colangelo, an NBA lifer who’d gone to the University of Kansas in the 1950s to play alongside Wilt Chamberlain, only to be disappointed when Chamberlain bucked the convention of his day by leaving school after his junior year to play a season with the Harlem Globetrotters. In just a few pages Abrams gives us a microcosmic swath of the NBA’s youth movement from Chamberlain to the early 2000s, with the figure of Colangelo— who went from objecting to the prep-to-pro movement to cannily drafting future Rookie of the Year Stoudemire—standing as a sort of weather vane of history.

Just as affecting are the stories of those who never made it. There’s the case of Leon Smith, a 1999 first-round pick who attempted suicide in November of his rookie season, stalked by mental health problems that had long been ignored by everyone who’d used him throughout his young and talented life. Or Lenny Cooke, one of the last great New York City schoolboy phenoms who, after a calamitous encounter with another young prodigy, endured the prep-to-pro generation’s most spectacular downward spiral, basketballwise. (Once the most touted player in his high school class, Cooke went undrafted in 2002.) Or, strangest of all, the quixotic tale of Taj McDavid, a California high-schooler who entered the 1996 draft alongside future All-Stars Bryant and Jermaine O’Neal, despite not even having been recruited by major college programs.

Abrams is a reporter first and foremost, drawn to the stories and their details, and there are broader themes here that are ripe to be explored more thoroughly. Race, for instance, looms enormously. With the exception of underachieving big man Robert Swift the prep-to-pro generation was almost entirely black, and the public pearl-clutching over immaturity and cultural decline would never have been so pronounced if the skin in the game had been another color. Class is another: Boys Among Men counters the stereotype of these athletes as monolithically “at risk” and driven by economic desperation, a telling that negates agency under the guise of paternalist concern. For the most part, Abrams makes clear, these were not decisions that players were forced into, but rather decisions made out of ambition, self-interest, and foresight. And far more often than not, they proved to have been made correctly.

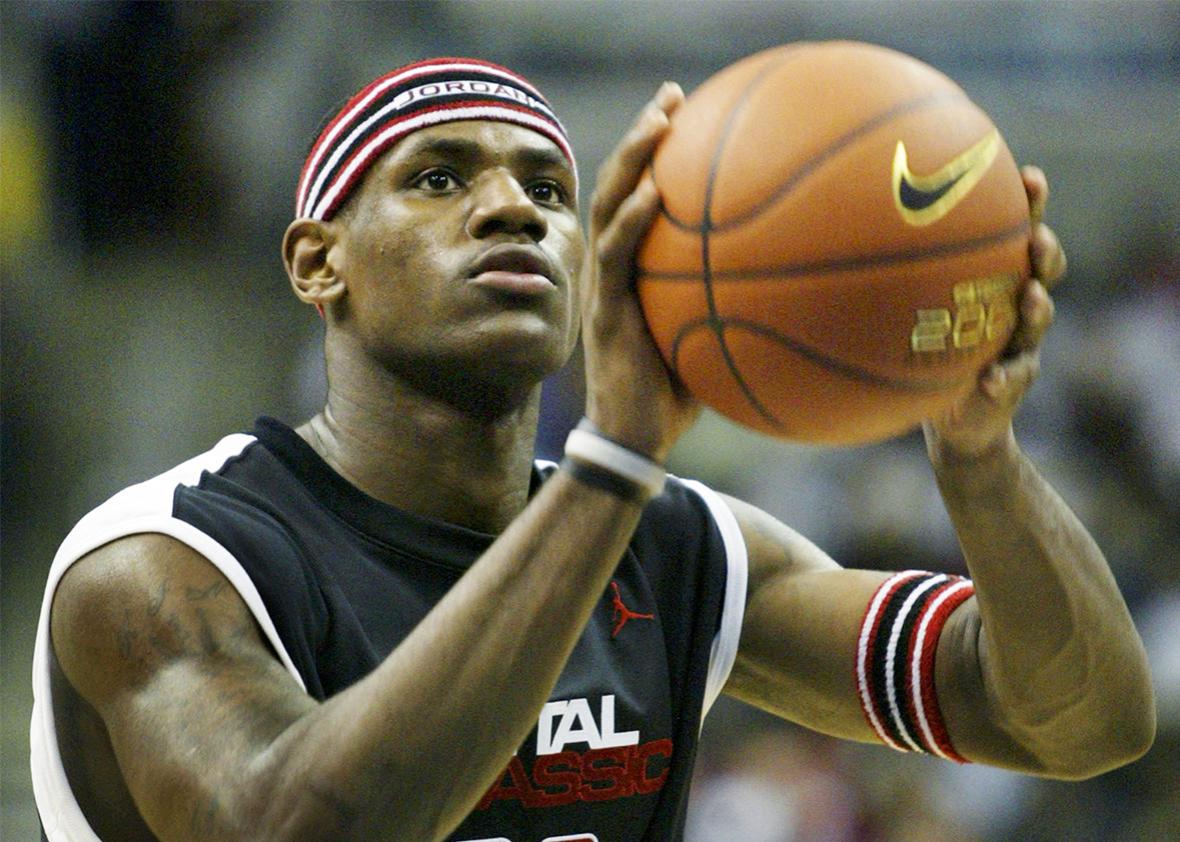

Abrams lets the broader implications of his reporting go mostly unspoken. But others will chase down and expand upon these threads, particularly now that Abrams has provided the materials to do so. Boys Among Men’s greatest achievement is its vivid documentation of young men who truly did change the face of a sport, and to no small degree a culture. About two-thirds of the way through Abrams’ book is the story of a boy born to a 16-year-old single mother who barely knew his father and who, in Abrams’ words, “moved from one friend’s house to another and from couch to couch” while missing “days and weeks of elementary school at a time,” even spending two years of his adolescence living with his youth coach. By the time he’d entered the NBA Draft in 2003—just a couple years after he’d shockingly dominated Lenny Cooke at the prestigious ABCD camp—controversies over cars and clothes led some to brand him the newest and worst symptom of his sport’s downward spiral. Basketball turned out OK, and so did LeBron James.

—

Boys Among Men: How the Prep-to-Pro Generation Redefined the NBA and Sparked a Basketball Revolution by Jonathan Abrams. Crown Archetype.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.