Beverly Cleary turns 100 on April 12, and most of the attention surrounding this happy event has, understandably, celebrated Ramona Quimby. Ramona entered the scene as a minor character in Cleary’s first book, Henry Huggins, and then starred in eight more books between 1955 and 1999. Set in Portland, Oregon, the Ramona series brilliantly portrays younger children and their concerns: the difficulty of sitting still in school, mourning a cat who dies, feeling jealous of a big sister. Feisty, imaginative Ramona is Cleary’s crowning achievement and the reason she will be revered for generations to come.

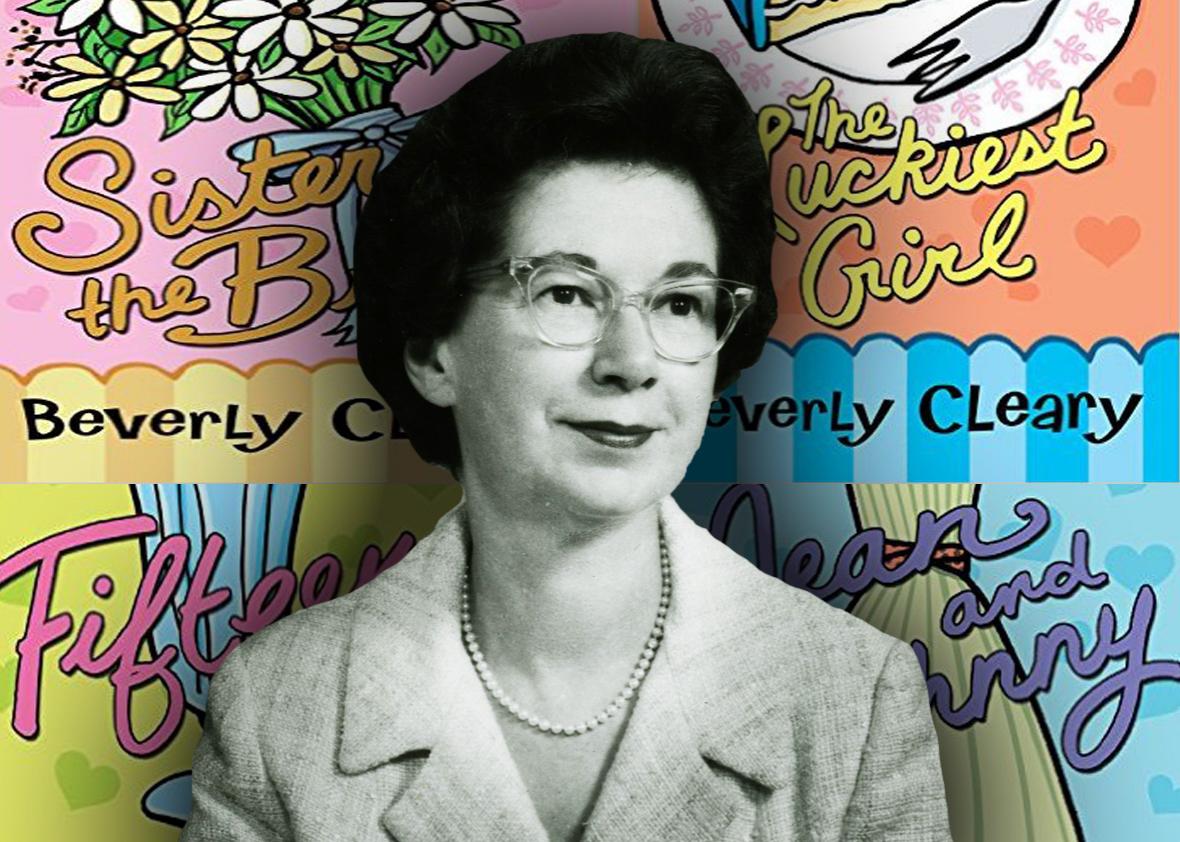

But small-girlhood wasn’t Cleary’s only concern. Four mostly forgotten novels she wrote a half-century ago depict teenage life as acutely as the Ramona series dissected childhood. They are also an intriguing time capsule of teen culture in the 1950s and early ’60s. The quartet deserves its own moment in this season of praise for Cleary’s important body of work.

Fifteen, The Luckiest Girl, Jean and Johnny, and Sister of the Bride are all set in California, where Cleary settled as an adult after a childhood in Oregon. They feature high-school girls in middle-class families, and their plots revolve around the agony and ecstasy of teen romance. (The HarperTrophy imprint of HarperCollins packaged them a few years ago as the “First Love” series, though the books stand independently and can be read in any order.) On the surface, the stakes are adorably low from a 21st-century adult’s perspective. Will a boy’s father let him borrow the car? Will the girl’s parents allow her to ride in it?

To use the lingo of their era, these novels are square. The protagonists have names like Jane and Barbara; they are not the misfits of which much teen literature is made but instead fundamentally good girls who long to fit in, and usually do. When Shelley of The Luckiest Girl starts her junior year at a new school, she sets her sights on a handsome basketball player, and he quickly asks her out. Jean of Jean and Johnny gamely describes herself as someone who would rather be a part of the cheering crowd than a rally girl out in front. It certainly never occurs to her to stay home from the game. Viewed through the lens of contemporary culture, and especially contemporary teen lit, these girls should be boring and shallow. But Cleary’s supposedly ordinary girls are complex: resentful of their mothers one moment and sympathetic toward them the next, willing to do anything for one special boy but indignant when they’re taken for granted.

Readers who return to the Ramona books as parents might be surprised at the extent to which seemingly adult woes about money are a steady source of tension in the Quimby household. Similar anxieties animate Cleary’s teen novels, too. In Jean and Johnny, the Jarrett family seems to be clinging to the middle class by the skin of their teeth: Jean’s mother works at a downscale fabric store on the weekends, buys the wrong (that is, cheap) kind of milk and butter, and in her spare time enters contests to try to win a new refrigerator or television set. Johnny, by contrast, wears shirts that need to be dry-cleaned. In Fifteen, Jane is relieved to hear that her crush’s family lives on Poppy Lane: “That meant they were neither very rich nor very poor,” she thinks to herself. If you grow up in a home in which these kinds of worries hum in the background of everyday life—and Cleary did, according to her memoir A Girl from Yamhill—the attention to them never fully vanishes.

I read several of these books as a preteen, returning over and over to Jean and Johnny in particular. In my memory, the book was thrilling—sexy, even, though my prudish 11-year-old self would have been mortified by the very word. Johnny is a rakish upperclassman who takes an interest in a 15-year-old who wears glasses and sews her own clothes. When Johnny unexpectedly asks her to dance with him, Jean careens between rapture and humiliation. Cleary spends 20 pages on Jean’s methodical preparations for a planned Saturday-evening Johnny visit: moving houseplants, making dessert, rehearsing some casual bits of flirtation. The tension is like something out of Ferrante or Chekhov. When he calls almost an hour late to tell her can’t come after all, it’s devastating.

When I was a girl, Johnny’s attention to mousy Jean seemed thrilling; as an adult, he comes with so many red flags he might as well be selling them. At the end of the book, Jean rejects him just as his attentions are drifting away anyway. This is a running theme in all four books: Better to like an interesting boy who actually likes you back than to waste time pining after one who, like Johnny, is both too good and not good enough.

Teen culture changes much faster than kid culture does, so Jean and Johnny’s story feels much more dated now than, say, Ramona’s. I don’t remember being aware as a child that Ramona was “born” in the 1950s, because her world was so similar to my own. But the fashion, foods, and family dilemmas in the First Love books are unmistakably dated. The protagonists have hobbies like sewing and flower arranging. Their love interests call them on the telephone, take them to formal dances, and ask them to wear their identification bracelets as a symbol of commitment. In 2016, these books read like historical fiction, which may have contributed to their lapse into relative obscurity.

Another thing that’s dated, or perhaps just tailored for preteen readers: No physical relationship in the books proceeds past a single kiss. But who needs kissing scenes when you’ve got erotic passages like the one where Johnny walks right up to Jean’s desk in the sewing classroom, looks straight down at her, puts his hand on her elbow, leads her out to the hall in front of all her classmates, and then softly whispers, “Did I ever tell you you have a cute little nose?” The first time something like that happens to you, it’s as physically overwhelming as anything that comes along later. Though Cleary doesn’t spell out the girls’ longings—these were the pre-Blume years, after all—she nonetheless captures the electrical charges of the years between puberty and sex.

Cleary’s protagonists may be chaste, but emotionally they are downright slatternly. These girls treat their teen romances like the ephemeral fancies they are. Three of the four books end with a girl who is happily unencumbered, sometimes dating multiple boys at once. In The Luckiest Girl, Shelley has a giddy epiphany that she has fallen in love—“not the love-for-keeps that would come later, but love that was real and true just the same.” Then she promptly moves out of town, wistful about leaving the boy behind but without entertaining the notion that she would do anything else. The book ends with Shelley alone, “happier than she had ever been in her life.” Cleary treats teenagers with the mix of empathy and clarity she applies to all her young characters: She takes their feelings seriously, but she is also frank about the impermanence of their dramas. The fact that she lets them cheerfully arrive at the same conclusion themselves is downright refreshing.

Sister of the Bride, the last book in the quartet, was published in 1963, five years before Ramona the Pest drew Cleary’s energies back to spunky young Ramona. It is the weakest of the four books, mostly because the main plot concerns a 16-year-old’s anxieties over her sister’s impending wedding and marriage, which gets pretty tedious. (“Barbara, who had pictured her sister floating down the aisle in a cloud of tulle, conceded that an old lace veil might be better than no veil at all …”) By then, the ’60s were intruding on Cleary’s teens: The bride, a Berkeley student, prefers pottery to china, dismisses engagement rings as “middle class,” and listens to Joan Baez.

The final book in the Ramona series finds the heroine turning 10 and contemplating what it will be like to be a teenager, and then a grown-up. “She felt the way she felt when she was reading a good book,” Cleary writes. “She wanted to know what would happen next.” I’d almost rather imagine Ramona staying 10 forever, but if she grows up to be anything like Cleary’s other teenagers she’ll have friend problems and school drama and money worries. At times, her clothes will be all wrong and the perfect boy will stand her up. Life will get complicated, or even sad and scary. But she’s going to be just fine in the end.

—

Fifteen, The Luckiest Girl, Jean and Johnny, and Sister of the Bride by Beverly Cleary. HarperTrophy.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.