Anyone fortunate enough to have published a book knows there’s a moment after you send back the final proofs, once the book is going to press for real, when a wave of relief sweeps over you—followed quickly by a bottomless sensation of dread. Suddenly you realize that it’s packed with mistakes—not outright typos so much as sentences you could have phrased better, points you missed making, whole passages you’ve recognized, too late, as utter drivel. Only now that you’ve committed to a permanent version of the thing do you grasp just how imperfect it will always be. And there’s absolutely nothing you can do about it.

Unless you are Karen Hall. In 1996, the veteran writer for such TV programs as M.A.S.H., Hill Street Blues, and Moonlighting, published a popular supernatural thriller about a Southern family persecuted by a demonic curse. Twenty years later, Simon & Schuster is releasing a new version of Hall’s only novel, Dark Debts, extensively rewritten, with a new character and a changed ending. Hall’s editor at S&S, Jonathan Karp, is the same one who, as a rookie, acquired the title for Random House back in the 1990s with the conviction that it would become a best-seller. “I loved the book,” he told me. “It completely captivated me, but as time went by, I agreed with Karen that it could have been even better.” So Karp offered to publish the book again once the rights became available.

This sort of thing almost never happens. Sure, every so often an author like Neil Gaiman gets to publish an anniversary edition of a best-seller like American Gods, a version that restores a few bits cut from the novel during editing the first time around. But he doesn’t substantively change the book. Most famously, Henry James spent the last years of his life producing the “New York edition” of his collected fiction, rewriting many of his early novels and stories in the clause-rich (and, some would say, even more maddeningly vague) prose of his late style.

But Dark Debts isn’t a Henry James novel. It isn’t even American Gods, and the alterations Hall has made are more than just a refinement of her style. “I always knew I was never going to write another novel until I fixed this one,” Hall told me. “I wrote it when I was 20 years younger, during a time when I thought I’d solved all the problems in the universe and needed to explain them to people.” Yet while Hall describes herself as less “certain” now, the new version of Dark Debts seems more so. The story of its transformation exposes paradoxes at the intersection of faith, progress, and popular culture.

Dark Debts belongs to a particular vein of entertainment: tales of evil spirits, their victims and the brave heroes who fight them. The Exorcist—book and film—is a touchstone of the genre, and a major influence on Dark Debts, as Hall freely acknowledges. Typically, the plots involve a character, often a child, possessed by a demon that manifests its power in disgusting and horrid ways. Sometimes a house or other building is bewitched. The characters spend a while trying to come up with natural explanations for the otherworldly shenanigans. But once they’ve accepted that the cause is supernatural, they call in an expert to help them get rid of it: if not an outright exorcist, then a ghost hunter using similar techniques, like Ed and Lorraine Warren, a real-life couple whose exploits have been turned into best-selling books and films from The Amityville Horror to The Conjuring.

For a nation that’s only 21 percent Catholic, America sure is fascinated by exorcism. Still, there’s a glaring absence in most demonic possession stories—and in fact in most supernatural yarns where vampires and other monsters recoil from crucifixes and holy water. A belief in demons that can be driven out with religious artifacts and rituals implies a corresponding belief in the power of those objects and rites, and the faith that created them. If the Devil who appears in, say, The Witch is real, then doesn’t that imply that the God worshipped by the beleaguered Puritans in the film is real, as well? Otherwise, why would the Devil want to capture their souls? Remember that the Devil is also known as the Adversary; he only makes sense in opposition to a corresponding entity who stands for good.

Yet most supernatural thrillers in print or on screen duck this implied endorsement of Christianity. Their audiences come to them for creepy fun, not theology. Dark Debts, however, is different. Hall, who had a booming career in another medium, wrote it not because she wanted to launch herself as a horror novelist but because she’d become preoccupied by metaphysical questions. “I told everybody I was writing a book about the nature of evil,” she told me. “I felt hip and cynical saying that at cocktail parties in Los Angeles. As I got into it, I realized that I couldn’t write a book about the nature of evil unless I was willing to look at the nature of good.” She’d started writing Dark Debts—which features a doubting, liberal Jesuit priest as a central character—thinking of herself as an agnostic, but by the time she finished she’d converted to Catholicism.

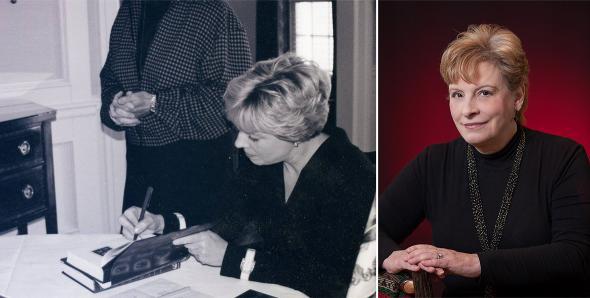

Photo courtesy of Karen Hall. Photo by Jean Moree.

This new version of the novel more accurately reflects her faith in the church that, 20 years later, she remains devoted to. It’s not clear that’s made the novel better, though. It’s true that much of the prose is sharper. So much of writing well is knowing what to leave out, but most of the time the knack for knowing how to cut is invisible; a reader can’t know what the author thought better of including. In the new Dark Debts, we have a chance to see how cuts can improve a passage immensely. In just one of many examples, Hall trimmed the closing sentences of an early paragraph describing a character’s response to learning of his brother’s suicide:

He drained the last of the whiskey. He put the cap back on the bottle, stared at it for a moment, then hurled it at the side of the depot, where it shattered and fell to the ground in a thousand pieces. It was the closest thing to an act of violence that Jack had committed in 10 years. The sound sent a cold echo through his hollow soul.

The new version loses that (quite awful) “hollow soul” and makes the violence part of the action, not something the narrator tells us about after the fact:

He drained the last of the whiskey. He put the cap back on the bottle, stared at it for a moment, then hurled it at the side of the depot, where it shattered and fell to the ground in a violent spray of a thousand pieces.

But if the surefootedness that Hall’s prose has acquired over the years is an improvement, the firming up of her religious views is another matter. True, the 1996 version of Dark Debts is a bit of a mess; Michael’s liberal-minded reservations about the Catholic Church—from its relegation of women to second-class status, to its hierarchical ass-protecting, to the pedophilia scandals decried in Dark Debts five years before the Boston Globe began publishing its celebrated exposés—balance out the revelation that diabolical spirits actually exist and can be combatted with faith in the one true church. But the church is just as flawed at the end of the book as it appears to be in the beginning. In fact, it’s demonstrably more so, since the skeptical authorities in Michael’s diocese had denied an earlier case of demonic possession we now understand to be true.

In the new version of the novel, Tess, Michael’s secret girlfriend, has been made less appealing, and Hall has cut a fierce speech in which she complains that the Vatican treats the rights of women like “a shrugged-off side issue.” In 1996, the likelihood that Tess and Michael might make a fine life together tugs hard on the novel’s unfolding narrative; pop culture, the industry that Hall has worked in all her life, has made its own kind of religion out of romantic love. We often feel that a story hasn’t reached a satisfying resolution until its central heterosexual pair achieves a happily-ever-after ending. Hall says that in the past 20 years she’s become “a much more traditional Catholic,” one who no longer shares Michael’s reservations about priestly celibacy. “I was single and romantic, then,” she told me. “Now I’m happily married and calmer about stuff like that.”

When Hall describes herself as less “certain” now, she means that she’s no longer convinced that traditional Catholic doctrine needs to be changed. The new character she’s added to Dark Debts, a conservative Jesuit, stands poised to welcome Michael back into the celibate fold. The plot, like the prose, is tighter, but that’s the confounding thing about novels: They’re often better, or at least more alive, when they’re flawed and messy. (It’s only the great and very rare practitioners who can succeed with perfection.) The original 1996 Dark Debts is a thriller of modest accomplishment animated by the passions of a writer wrestling with clashes between what amount to two faiths, between romantic and spiritual love, and between a religion and the institutions that profess but fail to uphold it. What it lacks in finesse and artistry, it makes up for in immediacy.

That version of Dark Debts may be less polished than its new incarnation, but it has the feverish air of a dispatch sent directly from the field of battle, complete with bloodstains, a whiff of gunpowder and a vivid sense that the stakes are life and death, even if it’s not always clear who’s on which side. Technically, the new version is a better, more coherent book, and the temptation to revise it is understandable. But—for this impious reader, at least—it’s also a temptation worth resisting.

—

Dark Debts by Karen Hall. Simon & Schuster.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.