A rule of thumb: The more avidly you want an explanation of the meaning behind a powerful and cryptic work of art—from David Lynch’s Mullholland Drive to Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis—the less satisfying and comprehensive the answer can ever be. Sometimes how a book or a film puzzles you—how it may mystify even its own creator—is the main point. The way it keeps slithering out of your grasp. The way it chats with you in the parlor even as it drags something nameless and heavy through the woods out back. The person who made it went off into the dark somewhere and came back holding this beautiful thing, a genuine souvenir. But can even she understand exactly what it is or what it’s for? Relax: You’ll never know. You can never know.

That’s the spirit in which to approach The Vegetarian, a novel by the South Korean writer Han Kang originally published as three linked novellas in her homeland in 2007, and now available in a pristine English translation by Deborah Smith. Although the title character, Yeong-hye, is a woman who suddenly stops eating meat one day, setting off a chain of catastrophes in her otherwise ordinary extended family, The Vegetarian is by no means a book about vegetarianism or the people who practice it and why. What The Vegetarian is about (always keeping in mind the caveat above) is abstention. Yeong-hye would prefer not to. At first she rejects meat, but eventually she will excuse herself from a number of other common human activities, as well. At last she refuses humanity itself.

The first part of this story is narrated by Mr. Cheong, Yeong-hye’s husband, an imperious dullard fully at peace with his own mediocrity. He chooses Yeong-hye because she strikes him as “completely unremarkable in any way” and because he correctly perceives that she will fulfill the duties of a wife without expecting anything more than the perfunctory obligations of a husband in return. She spends most of her time in her room reading. Then one night he finds her standing rapt before the fridge, pulling all of the fleshly contents out of its depths and dumping them into the trash. The only reason Yeong-hye offers for this radical decision: “I had a dream.” His wife’s refusal to eat, to cook, or to permit meat in her house persists to the point that Mr. Cheong fears she is hampering his unbrilliant career, so he appeals to her family. A dreadful scene ensues and Yeong-hye ends up in a psychiatric hospital.

The second part of The Vegetarian is told from the perspective of Yeong-hye’s brother-in-law, a painter and video artist who becomes obsessed with a vision, “the image of a man and woman, their bodies made brilliant with painted flowers, having sex against a background of unutterable silence. … One stripped-down, drawn-out moment of quiet purification, extremity sublimated into some kind of peace.” When he learns that Yeong-hye has a blue birthmark the size and shape of petal, he decides she must be the woman in this dream, and he develops a fixation on her that is equal parts creative and erotic. This shatters his marriage. The last section of the book, viewed through the eyes of Yeong-hye’s older sister, follows the vegetarian’s descent into full-blown madness and the ecstatic belief that she is in the process of becoming a tree.

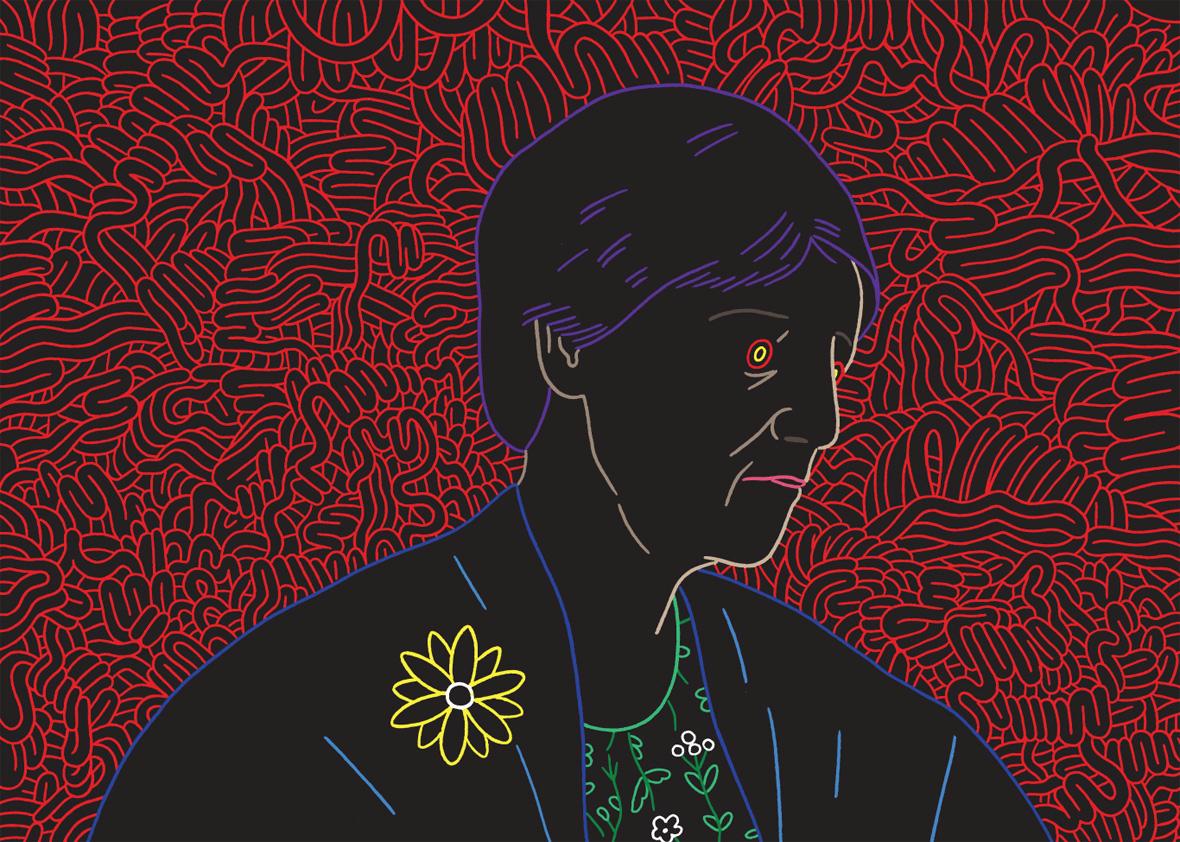

Perhaps it’s just my own Western upbringing, but the structure of The Vegetarian registers as devotional, a triptych that moves its title character closer and closer to a destructive transcendence that, in turn, infects those closest to her. Yeong-hye’s brother-in-law (never named) irritably vows that the images he wants to make will be much less carnal than an orgiastic video made by the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, but the aesthetic of Kusama’s late work haunts The Vegetarian. Kusama makes objects and spaces that look as if they’re in the process of being devoured by biomorphic growths, as well as images in which a figure (usually herself) appears dressed in a seething pattern exactly reproduced in the background behind her. It becomes impossible to detect the borders between one object and another or a person and the space he inhabits. The Vegetarian portrays this sensation intensified to the point of total ego meltdown: How liberating to dissolve into the vast vegetable kingdom, and yet, how frightening.

Park Jaehong

The effect of Kang’s prose is difficult to convey. I’ve scoured The Vegetarian in vain for a passage to quote that will illustrate how the novel transmits a feeling of great stillness even as its characters undergo convulsions of rage, sorrow, and lust. Plucked out of context, however, the sentences look bald and workmanlike: “He was honest to the point of seeming naive; exaggeration or flattery was entirely beyond him. But to her he was always kind, never once raised his voice in anger, and indeed would sometimes give her a look of great respect.” While the characters often don’t understand the source or meaning of their own feelings, they can always identify them, and Kang states them in a straightforward style that will remind many of Haruki Murakami. She also shares with Murakami a fundamental resistance to explanation underlying her propensity for plain talk.

Some reviews of The Vegetarian have insisted on viewing the novel as a piece of social protest, but this seems beside the point, unless the protest is against existence itself. Yeong-hye progresses through three stages of detachment, shedding herself first of the imperative to live up to empty convention, then of desire, and finally of the most primal attachments of blood and compassion. By the time her sister sits down in a hospital chair beside her haggard frame, and Yeong-hye triumphantly announces, “I’m not an animal anymore,” she has gone far past fretting about the pressures on women in Korean society, or any society for that matter. The Vegetarian has an eerie universality that gets under your skin and stays put irrespective of nation or gender. But exactly what its business is there, I would not presume to say.

—

The Vegetarian by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith. Hogarth.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.