The most memorable writing by physicians often comes about when the physician is knocked down by the very entity he or she strives to subdue: illness. Jerome Groopman’s The Anatomy of Hope is at its most intense and moving in the chapter where he reaches inward and describes his long struggle with back pain. Oliver Sacks’ wondrous late essays, in which he meditates on his own imminent end and the meaning of all that came before, glow with emotional resonance. In the hierarchical world of medicine, where doctors may have little experience with personal suffering and often remain emotionally disconnected from their patients, the doctor-writer who gets sick gains one benefit from suffering: a massively changed perspective.

Many readers may remember the profound and heart-wrenching 2014 New York Times essay, “How Long Have I Got Left?” by Paul Kalanithi, a young neurosurgeon barely at the end of his lengthy training who was diagnosed with metastatic lung cancer. Unlike Sacks, who had the luck to live a long and productive life and whose writing stretched over many decades, Kalanithi only covers his education and medical training in his memoir, When Breath Becomes Air, because he died at the end of his neurosurgical residency. There’s no possibility of a book tour, of a good-natured NPR interview, of another book from this talented writer.

The first half of the book is a fairly typical young doctor memoir, peppered with details from his Indian American background, his love of literature and philosophy, his adventures as a medical student and resident. There are plenty of literary references, and his prose is careful and appealing, telling the kinds of stories that might happen to any young doctor:

I slipped out of the trauma bay just as the family was brought in to view the body. Then I remembered: my Diet Coke, my ice cream sandwich … and the sweltering heat of the trauma bay. With one of the ER residents covering for me, I slipped back in, ghostlike, to save the ice cream sandwich in front of the corpse of the son I could not.

Thirty minutes in the freezer resuscitated the sandwich. Pretty tasty, I thought, picking chocolate chips out of my teeth as the family said its last goodbyes. I wondered if, in my brief time as a physician, I had made more moral slides than strides.

For the most part, the memoir’s first half feels familiar: yet another well-written young doctor memoir that would have been more interesting if he’d waited it out for a few years and gained some perspective. But Kalanithi understood this. He loved writing but realized that neurosurgical training and an active writing life were not a feasible mix. His original life plan, he writes, was to practice as a neurosurgeon for a few decades and then write a book. But with his diagnosis—and with his first, and only, child on the way—time was of the essence.

Kalanithi’s writing is urgent, and the most polished and poetic parts of the book are adapted from the few essays he published; the rest, if a little rougher around the edges, is suffused with intelligence and evidence of a rich soul. Kalanithi was attuned to himself through his training and had insight into his own foibles as he developed into a good doctor. He manages to be humble and self-critical, words not usually associated with neurosurgeons. “I was not yet with patients in their pivotal moments,” he frets. “I was merely at those pivotal moments.” With time, he learns that grasping the complexity of his patients’ brains is only part of the story—the effect of their illnesses on their lives matters, too.

Things fall apart in the second half, slowly and steadily; for months, Kalanithi fights his illness, continuing to charge ahead with his residency, determined to finish it, just in case he beats his cancer, while he loses weight and weakens. He writes with appealing honesty and bluntness about how he tried to ignore the warning signs—the fatigue, the weight loss, the back pain—even as he knew, deep down, that this was cancer. His oncologist withholds prognostic information when he asks for it, and he relents to let her take the reins, not easy for any doctor, especially a surgeon. It’s an insight into the mind of the oncologist, too, the tricky balancing act between hope and too much hope. Kalanithi’s depiction of the mind and motivation of an oncologist is the most effective I’ve seen; it’s easy to be critical of those who withhold prognoses, but here Kalanithi helps us see that it actually makes sense. An oncologist needs data points, needs to see how a patient does at each step; it’s not so easy to give a big-picture impression, at least not early on.

Photo by Norbert von der Groeben/Stanford Hospital and Clinics

Still clinging to hope—the cancer has been stable—and nearing the end of his residency, Kalanithi travels to Wisconsin for a job interview. It’s a dream job: millions of dollars to start a neuroscience research lab, a clinical service, a lake surrounded by faculty homes.* With a jolt, he realizes that he could never take this job, that he has at most a few years to live, and that it would be unfair to uproot his wife: “As desperately as I now wanted to feel triumphant, instead I felt the claws of the crab holding me back. The curse of cancer created a strange and strained existence, challenging me to be neither blind to, nor bound by, death’s approach. Even when the cancer was in retreat, it cast long shadows.”

Kalanithi’s book ends with a beautiful meditation on time, adapted from his essay “Before I Go.” It’s the kind of musing you’d expect from an old man, not a young one dying of cancer; yet despite cancer sapping his energy and preventing him from doing much of anything, he writes that “even if I had the energy, I prefer a more tortoiselike approach. I plod, I ponder. Some days, I simply persist.” And we can be grateful for his preference to ponder, because we are given this gift of a dying, eloquent man’s perspective on what it means to be facing multiple ends: of new fatherhood—his infant daughter is “all future, overlapping briefly with me, whose life, barring the improbable, is all but past”; of a career that was “relentlessly future-oriented, all about delayed gratification”; of identity—he asks himself which is more accurate: “I am a neurosurgeon” or “I was a neurosurgeon”?

After Kalanithi’s conclusion, his widow, medical school classmate Lucy Goddard Kalanithi, provides a lengthy and equally moving epilogue that seamlessly picks up where he left off; she describes, unflinchingly, his death and the aftermath. “Warm rays of evening light began to slant through the northwest-facing window of the room as Paul’s breaths grew more quiet. Cady rubbed her eyes with chubby fists as her bedtime approached, and a family friend arrived to take her home. I held her cheek to Paul’s, tufts of their matching dark hair similarly askew, his face serene, hers quizzical but calm, his beloved baby never suspecting that this moment was a farewell.” Her prose, too, is measured and lovely, and looking back, I could see that her writing style infused the book as she worked to bring the book to completion. While reading, I had worried that her presence in the book was less than I would have liked; I wanted to know more about their lives together, although understandably, much of his time had been filled by his grueling training and then his grueling treatment. I realize, in retrospect, that Lucy really was in the book all along, beginning in their sweetheart days in medical school. One night they work on cardiology problems together, and “while studying the reams of wavy lines that make up EKGs, she puzzled over, then correctly identified, a fatal arrhythmia. All at once, it dawned on her and she began to cry: wherever this ‘practice EKG’ had come from, the patient had not survived.” Lucy’s warmth and ability to feel deeply for others remains a steady undercurrent and influence on Paul until his death.

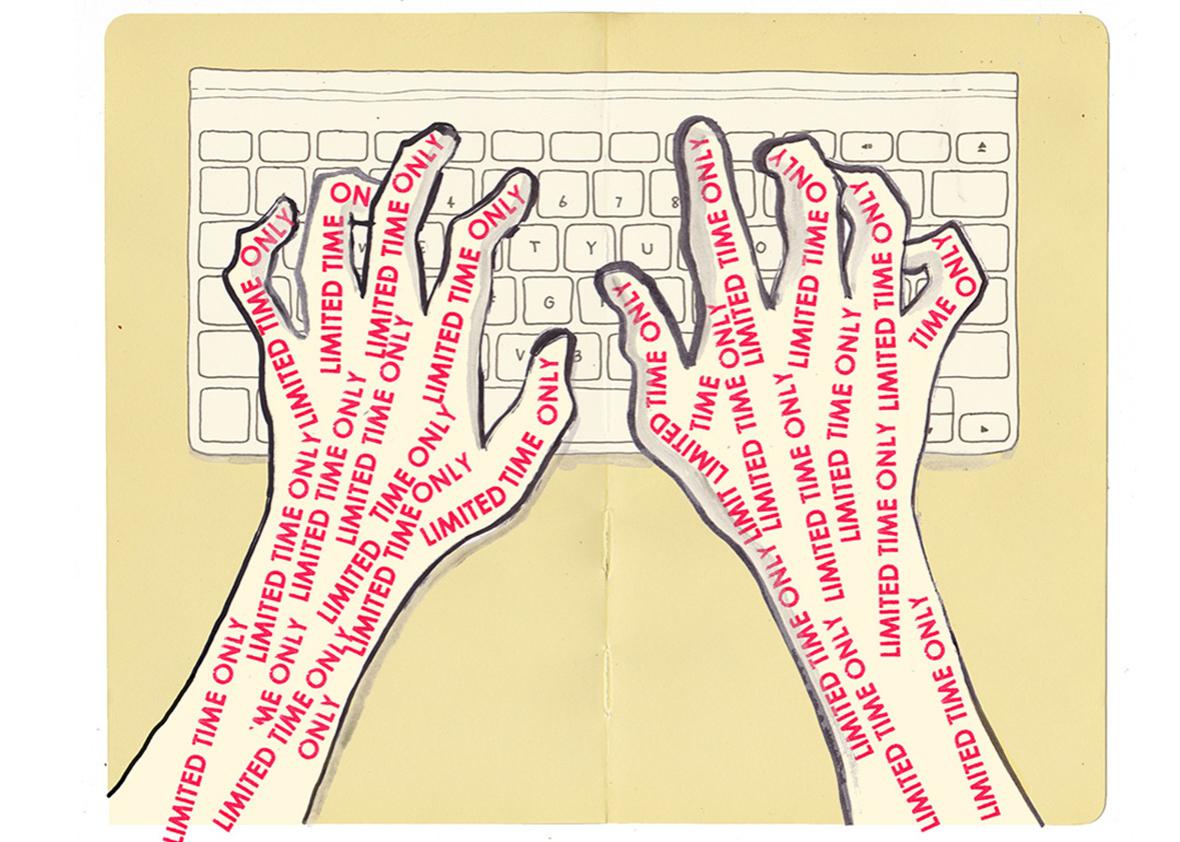

Paul, she writes, was “frail but never weak.” I picture him thin and intense, wrapped in a blanket on an armchair, computer on lap, writing this fine book with the pressure of the ultimate deadline.

Correction, Jan. 7, 2016: This review incorrectly described the position Kalanithi was offered late in his life. It was a position heading a clinical service, not a chairmanship. (Return.)

—

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi. Random House.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.