Shane McCrae is an alarmingly prolific poet—the author of three chapbooks and four full-length books in just five years. It’s easy to guess why: A victim of childhood sexual abuse raised by racist white grandparents who didn’t tell him his father was black, McCrae writes as though he’s trying to stitch the world together. His poems churn forward with terrible speed, sometimes seeming to throw words out in their own path in the hope of supporting an unstoppable forward momentum.

In the first poem from his latest book, The Animal Too Big to Kill, he begins in a characteristic mode, the repetitions keeping the meter alive as the ideas race ahead:

I haven’t Lord I haven’t You I have-

n’t praised enough You Lord although I with or would

With every poem praise You every breath and eve-

ry gesture praise you Lord

As the poem goes on, McCrae explains why God keeps coming up. After his conversion, he says, he learned to begin with God’s name

So that the day would be a prayer

And every gesture I made in the day

Believing

I could stay / Cool in the hot day

by running in the shadow of a cloud

It’s worth noting how McCrae manages such awful urgency: not only by moving so fast but by stopping so suddenly. “Believing,” with its implication of subsequent disbelief, works like a volta, a sudden turn into the impossible. There’s an element of ars poetica to these lines, a suggestion that McCrae’s constant rushing forward is a form of running for elusive cover.

The relentless movement isn’t always an asset. You sometimes get the frightening sense that McCrae is beholden to a machine of his own making, and parts of certain poems feel too mechanical, as if the engine keeps running absent the need it serves. When McCrae writes, for example, of “The Oak Ridge Boys or who / Was it who did that album with the spaceship banjos on the cover,” the consistency of his headlong style starts to feel like a kind of indifference to its materials.

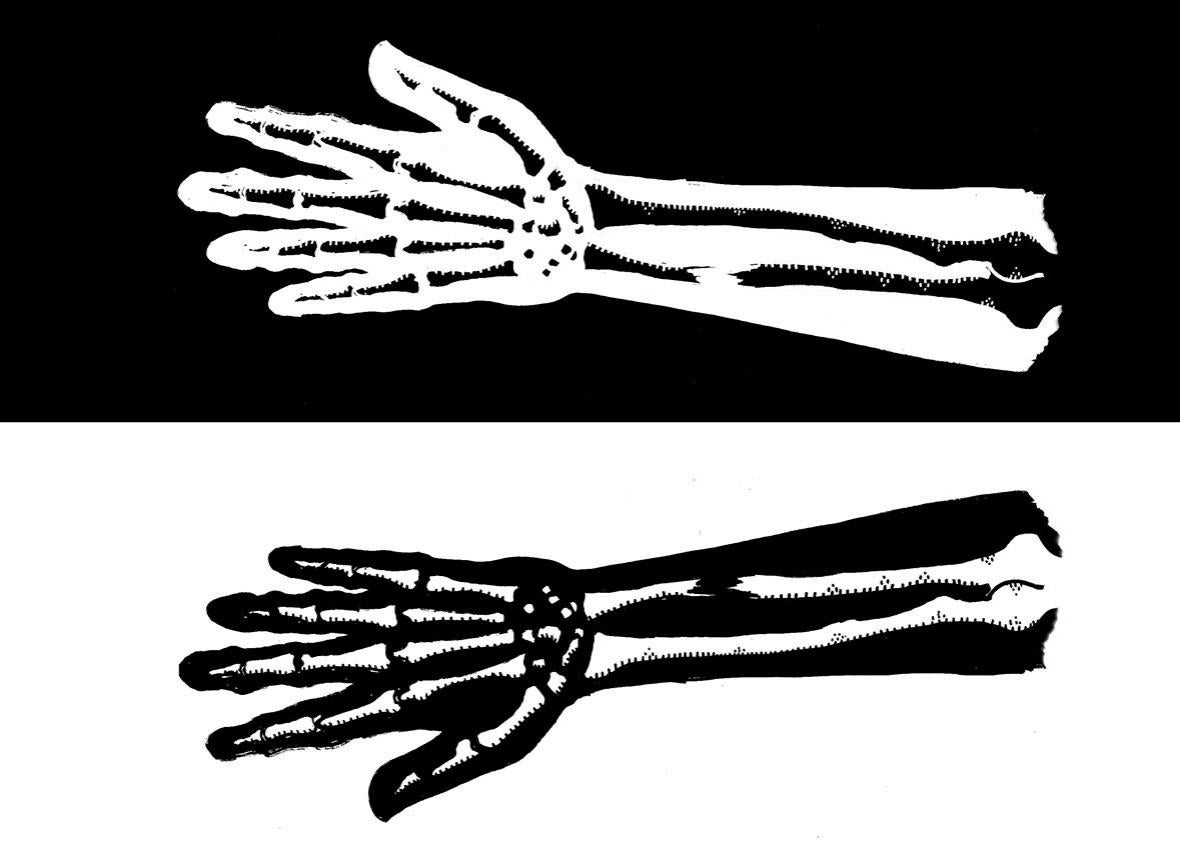

Image by Shane McCrae

But more often the style is steered by a surprising humility, an upshot, perhaps, of the profound damage racism inflicted on McCrae’s sense of self. This humility makes the poems’ frequent outrage all the more pronounced. You can see how hard he has to work to treat himself with kindness—to honor his woundedness with the anger it demands. Consider the poem ending the book, one of several about his guilt over eating animals. The phrase “have eaten animals” breaks apart painfully, almost incomprehensibly, over three lines:

Lord I have eaten and I don’t

Want to and have to

anyway / Sometimes because I can’t afford to eat

According to my conscience animals

The complications of kindness—which are, etymologically and actually, the complications of kinship—drive much of McCrae’s writing about religion. McCrae takes Christianity’s emphasis on poverty seriously; a couple of poems early in the book even try to tell God what it means to be poor. The first softens as it goes, incarnating Jesus’ earthly despair:

Maybe You suffered in Your body first the suffering of in Your body Lord

Inhabiting Your poverty

Maybe Your body Lord was shaped by foods You hated

Maybe You sometimes walking the market / Felt everybody even only

for a moment / Glancing at You

But the second moves in the opposite direction, landing at last in a trio of lines that scold God as they try to forgive someone else: a co-worker from a brutal assembly line job who denied McCrae comfort (the freedom to sit while he worked to relieve the pain in his feet) that would have cost her nothing:

I tell You now I know it Lord it love is truly is

Stronger than hate

Only for those who can afford it

In first establishing and then, after the line ends, rescinding the doctrinal position that love is stronger than hate, McCrae sharpens the bitter rebuke. And his repetition—“is truly is”—takes on the weight of this reversal, registering both hesitancy and conviction. McCrae needs to make God recognize what he said, in the prior poem, God must already know: “I don’t understand it why I think it Lord You don’t / Understand money / but of course You do.”

But McCrae has had to inhabit more than just poverty. He must live in his own skin. As he explains in the second half of a poem called “In of Body,” you (and by you he means himself):

… grow up wondering you

are raised

Wondering what you did and when Lord wrong to

Deserve your skin / You grow up wondering you / You

grow up standing Lord outside yourself and sometimes it’s not bad / You ride

your in your body bike

but no matter how hard you pedal how

Steep Lord the hill you dive down head first almost falling like you’re falling down

You stand

Outside yourself stand still

Like how it seemed when you were younger Lord like the world moved beneath

The wheels of the car and car didn’t move

“In of Body” shows up halfway through a group of eight poems that are, to my mind, the book’s best. The sequence (the first is called “Exile from the Supremacy”) describes McCrae’s double life inside his skin and inside a racist culture. “You grow up white,” he writes,

But not a white that counts it makes

People uncomfortable

All of the poems begin with the same five words: “Growing up black white trash.” A modifying phrase whose brutality dominates whatever it describes, the clause packs together racism, contradiction, disdain for the poor, and, in our expectations about what should follow “growing up,” sentimental notions of childhood. The concluding term, “white trash,” is especially loaded; on top its obvious viciousness, the addition of the adjective suggests that ordinary “trash” is black, and yet the phrase persists in places where most epithets are, thank god, impermissible. “Black white trash” is alive to all these contradictions, and alive, too, to the self-loathing McCrae internalized among people terrified of being seen as trash.

McCrae writes that “Being claimed by” whiteness

Felt Lord as natural as money natural as

money feels Lord when after weeks without

any Lord not a single

Dollar you come across a little

And for the hour you have it

Or maybe a whole day / If you lucky can make it last a day

You are yourself again

Of course, being yourself is never simple, especially for McCrae. In the conclusion of “In Exile,” a T-shirt becomes, briefly, a second skin, even as his actual skin houses him in annihilating contradiction:

Wishing your skin could somehow

suffocate you in your sleep

Growing up drawing swastikas on t-shirts

Growing up raised / By whites and white

things you can’t keep

The “white / things you can’t keep” (notice how he once again erases an apparent meaning after the break) include, presumably, his imagined skin. Whiteness was an aspiration McCrae could neither achieve nor give up. In another poem he concludes,

Growing up raised by white

supremacists / You grow up skinned / You make

a puppet of your skin

Meaning, in these poems, is relentless. Stories hurtle down the page, their details at once painfully literal and flagrantly metaphorical, as in the conclusion of “How You Are Owned”:

You grow up never sure you see yourself in mirrors

You grow up thinking what you see / Is only it might be

90% / Accurate maybe less

So that when you at 14 for the first

time break a bone / You when the doctor shows you

The x-ray think it looks

more real than you are

In the middle of a black void Lord you see

a broken white bone glowing

Here, as in so many of these poems, the meaning is all awful and excessive, almost more than the details can bear. The pleasure of the poem comes in McCrae’s ability to steer what can’t be slowed. McCrae typically ends his poems by veering suddenly, as in the punch line of a shocking joke, grabbing hold of the lines’ momentum and momentarily asserting his control (and thereby, paradoxically, making the violent power of his materials palpable).

And yet, wrestling with such horrible force and violence, he remains remarkably generous. That McCrae insists throughout on learning from the cruelty of others is not necessary to the value of poems like these, but it’s stunning, too. The book ends in a reckoning that imagines the sacrifice of the very flesh McCrae has worked so hard to claim:

Maybe if all the meat I’ve eaten since I started

eating animals again were piled and weighed

It would weigh as much as maybe if my leg were cut off

Below the knee the calf the shin the foot

Were laid in a scale opposite the meat

Maybe the scales would balance

As with the phrase “running in the shadow of a cloud,” this closing line is momentary, aspirational, unsustainable—“maybe.” The scales probably won’t balance. The shade will outrun him. But McCrae’s harnessings, hopes, and frantic alignments aren’t empty gestures. Their aspiration is real. The poems, inside their terrible machinery, are unusually alive.

—

The Animal Too Big to Kill by Shane McCrae. Persea.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.