”If you are in a sexy mood the night you read [my autobiography], it may stimulate you beyond recognition and rekindle memories that you haven’t recalled in years.”

This sentence was written in a personal letter by Groucho Marx to his frenemy, T.S. Eliot. Groucho had dropped out of elementary school, and for the rest of his life strove to prove himself a man of letters, as well as to discredit men of letters. In both his private and public humor he relied heavily on words, yet had a knack for exposing all words as ultimately contentless. Hence his desire to have Eliot read his autobiography—thereby legitimizing it—as well as his need to deflate the great poet into an impotent man with a “sexy mood,” but no recent sexual activity.

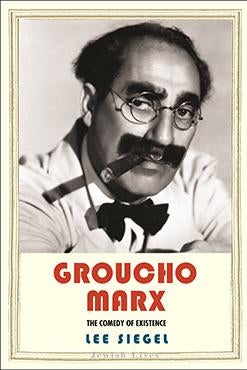

This account of Groucho’s correspondence with Eliot is among a number of revealing scenes in Lee Siegel’s Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence, and as the book is a critical biography, all such scenes are in service of a literary and philosophical analysis. This is what explicitly distinguishes this book from previous Marx biographies: In Siegel’s hands, the details of Groucho’s life are less interesting than the broader literary argument that they illustrate, which Groucho would have found both deeply validating and kind of annoying. To any literarily or philosophically inclined Groucho fan, however, the book is a luminous delight.

Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence is in itself a kind of funny title. Not only does it feature the scientifically funny hard-C sound, but it’s also deeply pretentious. And pretentiousness, being a form of ego-inflation, is among comedy’s most reliable targets. So it’s a self-defeating title: a reader who understands the comedy of existence would also make fun of the phrase “the comedy of existence.” Inspired paradox is at the heart of Siegel’s understanding of Groucho. He argues that the Marx Brothers’ comedy seeks to destroy everything, including the possibility of comedy itself. “Well, all the jokes can’t be good,” says Groucho in Animal Crackers. “You’ve got to expect that once in a while.”

Siegel observes that the Brothers routinely let loose streams of cascading puns, malapropisms, word associations, and seemingly pointless slapstick that are perplexingly bad and often aggressively anti-comedic, but taken collectively become overwhelming, and thereby hilarious. In the words of the 1930s film critic Otis Ferguson: “You realize while wiping your eyes well into the second handkerchief that it is nothing so much as a hodgepodge of skylarking.” But as Siegel explains, when the bad jokes relentlessly pile on, they reduce “language to sounds, intellectual life to disorder, and emotional life to physical gestures.” In the wake of this nihilistic force, our only physical response can be laughter. The Marx Brothers’ humor therefore exists “on the threshold of first and last things—that is to say, philosophy.”

When Groucho first encounters Harpo in Duck Soup, he asks him who he is, and Harpo answers by rolling up his sleeve and revealing a tattooed image of his own face. This answer transforms Groucho’s social request for an introduction into a fundamental philosophical question: Can we ever pinpoint a person’s true identity? It also asks an even more fundamental question about representation in language: How can we point to something in the world with complete accuracy, without also being meaninglessly redundant? Harpo’s answer to “who are you?” is a visual-gag version of the Buddha’s infuriatingly honest answer to the same question. When asked who he was, he would say, gesturing to himself: I am thathagatha (the one who is like this).

When people talk about comedians as philosophers, they often mention George Carlin, Sam Kinison, or Louis C.K. These are comics whose jokes contain broader wisdom about human nature, society, language, and sometimes the humor of existence itself. These comedians are people with Something to Say. But Groucho doesn’t have anything to say. (And Harpo, for that matter, has literally nothing to say.) For Groucho it is the aggressive lack of agenda that makes him more than just a philosopher—that makes him a living philosophical force, a human argument against any attempt to make meaning of anything or stand for something. The refrain of his introductory song in Horse Feathers: “Whatever it is, I’m against it.” At the same time, standing for nothing also lets him stand for anything: “Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them … well, I have others.”

If this essay feels more like a philosophical treatise than a book review, that’s because Siegel’s book reads more like a philosophical treatise than a biography. And yet Siegel somehow manages to make this treatise a true page-turner and a lot of fun. He applies his own philosophical acuity to the personal and socio-political aspects of Groucho’s life. He exposes the paradox behind Groucho’s misogyny, without excusing it—Siegel points out that there is a conscious impotence in Groucho’s repeated insults of women, on-screen and off: “He makes certain that it is an expression of male weakness, not male strength.” Siegel’s theory is that Groucho’s attitude toward women was a symptom of early 20th-century Jewish humor, and a result of being personally frustrated with a weak father who was prone to theatrical expressions of authority and bravado.

Image by Christina Gillham

Siegel’s understanding of Groucho’s Jewishness is layered with useful complexity. (This book is part of Yale University Press’ Jewish Lives series.) He provides a close reading of Groucho’s famous line: “I don’t want to belong to any club that would accept me as a member.” Groucho used this line in a telegram he sent to resign from an actual high-brow social club to which he felt superior. Siegel reads the line as equally self-annihilating and triumphant. So Groucho is an example of an early 20th-century Jew asserting dominance over American society by making his role as a permanent outsider part of mainstream American culture.

Siegel sees a philosophical paradox in every facet of Groucho’s life and art. Interestingly enough, the one issue on which the book is consistently ambivalent about is whether we can call the Marx Brothers “funny.” I don’t think this is so much a critical oversight on Siegel’s part as it is a testament to the Marx Brothers’ genius, as well as proof for Siegel’s argument that the Marx Brothers’ comedy destroys everything, including comedy. Siegel provides multiple arguments for how the Brothers are “something more or less than funny,” or “too nihilistic for laughter.” But at the same time he repeatedly refers to them as “funny,” too. There is a missing argumentative step that the book seems afraid to articulate, maybe because it’s self-contradictory: that this comedy, which goes too far past comedy into pure nihilism, still works as comedy, and that this in itself is funny.

Siegel offers extended analysis about how, in its essence, their work is not comedic. He quotes a bit of funny dialogue from A Night in Casablanca and then adds to the dialogue some lines from a real recorded domestic fight between Groucho and his wife, to demonstrate how easily the comedy can be transformed into drama—that it is not “essentially funny.” This misses a larger point that the Marx Brothers (and this book) seem to be making, which is that nothing is funny in essence, or not funny in essence, that comedy and drama aren’t opposed, that nothing has any essence at all. And that when we notice this, we laugh.

–

Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence by Lee Siegel, Yale University Press.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.