The power of imprecision has long fascinated China Miéville. In his sprawling 2002 novel The Scar, one character wields a mysterious and “puissant” artifact, a “possible sword” that strikes everywhere its blows might have landed rather than the single spot at which they were aimed. As the blade’s master explains, to maximize its effects he had to learn to fight more carelessly, sometimes swinging wide so as to maximize the potentiality, and hence the power, of his attacks.

This same trope makes a new appearance in Miéville’s latest novel, This Census-Taker, though by now it’s clear that he’s applied the same techniques to his own work—with sometimes mixed results. When he’s at his most imaginative, his stories are storms of ideas, flurries of concepts that pelt the reader like hailstones. Within the weird worlds of his novels, anything that might be is, the strange tangoing with the stranger. Nevertheless, more than a decade after The Scar, he’s still weaponizing the very idea of inexactitude: Late in the new book, the titular civil servant shows off his own armament, a double-barreled rifle that fires buckshot from one of its ports and solid slugs from the other. “It spreads possibilities,” he tells the story’s young narrator. “Like an average. A range and its mean. This is an averaging gun.”

It’s unlike Miéville—who is prodigiously creative—to recycle ideas in this fashion, but the resurgence of this one speaks to his larger concern with the rejection of easy genre boundaries. The possible has long been the domain of science fiction, a genre that thrives on could bes and not yets. Fantasy, by contrast, typically treads more unknowable ground, its narratives both woven of and emerging from the fog. There are rules in fantasy worlds, but we don’t always have access to them, and even when we do the greatest delight often comes from watching them crumble. What else is a wizard’s spell but an ignorance machine?

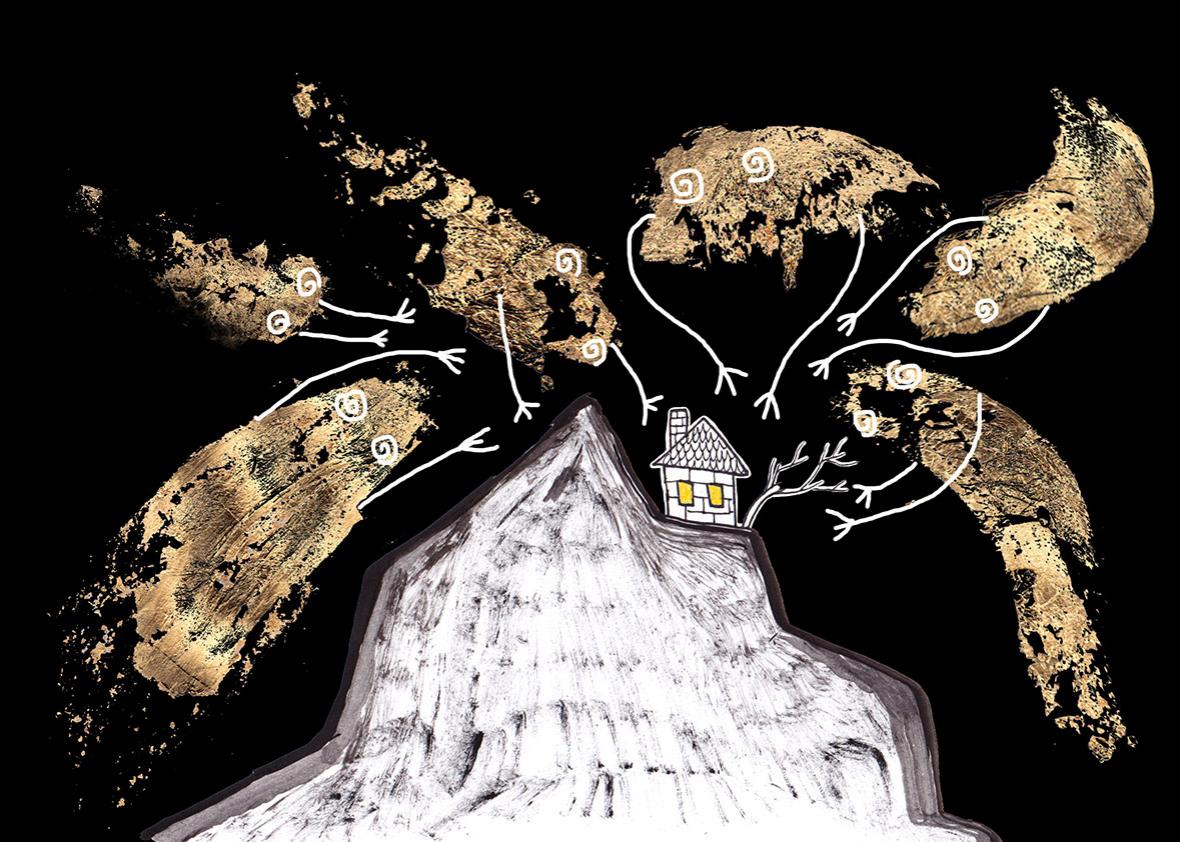

In the steampunkish worlds of Miéville’s fictions—and perhaps in This Census-Taker most of all—the possible and the unknowable meet in the uncertain. For most of his new book’s length, its narrator lives in his ramshackle family home on a rough and uncivilized hill. There are, he sometimes suggests, creatures on that hill at night, dangerous creatures, possibly even monstrous ones. And yet we never quite glimpse them. By day, things larger than birds sweep their shadows over the ground, but they fly so high that we never learn whether they’re dragons or airplanes. Indeed, though there’s talk of weather-watchers and hermits and witches elsewhere on the tangled slope, it’s hard to say whether this is a truly magical world or merely one of pervasive superstition.

That indeterminate quality bleeds out into the narrative as a whole. When we first meet the narrator, he’s just witnessed an unthinkable act, one of his parents killing the other. At first he thinks his mother was the perpetrator, but as he lays his tale out to the residents of the town below, he realizes that she was the victim. By the time officials arrive at his home to investigate, however, all traces of the act—if it occurred at all—have been erased. Told that his mother simply left, the boy must remain with his bloodthirsty father, each new violent act further eroding his confidence in his family, in what he saw, and in himself.

Photo by Chris Close

Always an ambitious prose stylist, Miéville finds an analogue to this climate of uncertainty in his novel’s narrative voice. It’s there from his first sentences: “A boy ran down a hill path screaming. The boy was I.” Such shifts from the third person to the first (and back again) recur regularly throughout, as if to capture the effects of his traumatic uncertainty—or, perhaps, the uncertainty that accompanies trauma itself.

As these hairpin point-of-view shifts suggest, Miéville is a bold writer, though in this case his boldness sometimes impedes empathic identification with his narrator. He’s also a broad writer—sometimes too broad. Here, for example, is the narrator describing his first glimpse of an exotic sea creature:

There I, who’d known only the fierce spine-backed fish of the mountain streams and their animalcule prey, came to a sudden stop, slack with awe before a glass tank big enough to contain me, transported at some immense cost for I don’t know what market, full not with me or with any person but of brine and clots of black weed and clenching polyps and huge starfish, sluggishly crawling, feeling their way over tank-bottom stones like mottled hands.

Though it can shade to purple, Miéville’s baroque language—his archaic vocabulary and obtuse phrasings—serves a purpose. In its excess it sketches a kind of engaged bewilderment, underscoring the essential otherness of the worlds he imagines into being. In This Census-Taker, that’s of a piece with the book’s general commitment to uncertainty, its elaborate phrases amplifying the interrogative demands it makes on the reader.

At its most obtuse moments, This Census-Taker feels as if it had been crafted out of the cast-off fragments of an unfinished Samuel Beckett novel. And yet occasional images of unusual beauty await the attentive and patient: On the underside of a bridge, a gang of children casts rods out into the air, trawling not for fish but for bats. In his workshop, the narrator’s father dips his fingers into colored powders to shape keys that may unlock strange powers. If these sequences sometimes befuddle they’re no less elegant for it. The very density of Miéville’s ideas both contributes to and compensates for our alienation.

Inevitably, enjoying this book means accepting that many of the questions it invites will go unanswered. Though the census-taker himself—whom we don’t even meet until almost three-quarters of the way through—deals in definite numbers and data, the book as a whole is uncertain to a fault, stranding us in the befuddled perspective of its narrator. Even the census-taker’s most heroic act—a successful resolution of the book’s central mystery—goes unexplained, except by implication.

For all my frustration with this opaque novel, I came to its end understanding that Miéville’s obscurantism serves one of his career-spanning themes—one that is, in fact, more evident here than in many of his more crowd-pleasing books. A political scientist by training, Miéville imbues his stories with a deep distaste for state-sponsored power. Census-taking is, of course, one mechanism of that power, a power that affirms and stabilizes itself through the elaboration of standards and norms. This census-taker, like the novel in which he appears, doesn’t quite fit the mold. He has, we gradually learn, gone rogue, suggesting that to reject statistical certainty may be to resist power itself. What does This Census-Taker propose that we put in its place? It’s possible that we’ll never know.

—

This Census-Taker by China Miéville. Del Rey.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.