Unable to sleep, a woman sits at the kitchen table or walks her neighborhood by night. She is 37, maybe 36. She is a wife and mother, roles that seem to have taken over her identity. Yet she looks down on women like that—most of whom, she can’t help noticing, are better at being wives and mothers than she is. She used to dream of art or writing or some other creative endeavor. Now, she takes pills. She’s bored. She’s anxious. She’s guilt-ridden. She’s exhausted and frustrated and probably depressed.

She is a housewife, which is to say that she is both the muse and the patron of the novel. However frantically male authors—and those of the 20th century in particular—have attempted to redefine the novel as a manly endeavor dealing with such important subjects as war and male ambition, the readership for fiction is and has always been predominantly female and middle-class. No wonder then that the greatest novels in several languages, from Middlemarch to Madame Bovary to Anna Karenina, concern themselves with heroines at odds with their own domestic fates.

As plenty of critics have observed, however, modern freedoms have sapped the potential for drama out of the housewife’s lot, especially if her discontent and transgressions are erotic. Anna Karenina sacrificed everything for love of her Vronsky. Emma Bovary’s illicit passions, while less elevated, exacted as harsh a penalty. An infidelity or a divorce today, while often grueling, is rarely so catastrophic. Yet housewives still feel miserable and trapped, and in their discontent, they still read an awful lot of books.

Not everyone is pleased with the persistent influence of the housewife. When the novelist Claire Vaye Watkins published an essay last year confessing that she had spent most of her career catering to the values and egos of literary men, the Jamaican author Marlon James retorted that writers of color were sick of pandering to white women, whose command of the literary community means that prizes and other accolades always go to books about a “bored suburban white woman in the middle of ennui”—in other words: housewives. That James had just won the Booker Prize for his novel A Brief History of Seven Killings took almost none of the sting out of that.

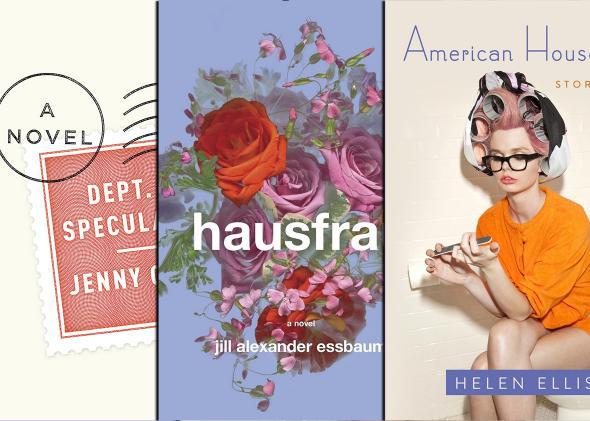

It’s a wonder that anyone has the nerve to write about housewives at all anymore: Not only are these women bored, but they have been universally declared boring. Yet last year saw the publication of Hausfrau, an acclaimed novel by the poet Jill Alexander Essbaum about a disconsolate American woman languishing in her husband’s stifling hometown in Switzerland, and this month brings American Housewife, a short story collection by Helen Ellis. Add to that Jenny Offill’s Department of Speculation, a 2014 novel that, while not technically about a housewife, wrestles with the same conflict between family life and self-determination, and it’s clear that the theme is enjoying a minirevival of sorts.

The last great heyday of the housewife novel was in the 1960s and 1970s, a boom ignited by Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and the rise of the women’s movement. Some of these books were tendentious, like Marilyn French’s The Women’s Room, others were literary, like Anne Roiphe’s Up the Sandbox, and still others were racy, like Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying and Judy Blume’s Wifey. Except for the racy ones, these books go largely unread today, and none more sadly so than what may be my favorite of the bunch, Sue Kaufman’s The Diary of a Mad Housewife. First published in 1967, Kaufman’s novel is out of print, and even the film based on it, starring an excellent Carrie Snodgrass in the title role, isn’t available on DVD. (Bless YouTube.)

Bettina Balser, the unhinged housewife in question, started out with the bohemian dream of becoming a painter, married an idealistic young district attorney, and then watched dumbfounded as he became a social-climbing corporate lawyer who treats her like a servant and whose contempt spreads to their two daughters. Behind her willingness to endure this situation lurks a therapist, Dr. Popkin, who has persuaded Bettina that a painter “is precisely what you cannot be. You must be what you are, not so?” Under his care, she “finally learned to accept the fact that I was a bright but quite ordinary young woman, somewhat passive and shy, who was equipped with powerful Feminine Drives—which simply means I badly wanted a husband and children and a Happy Home.”

The mad-housewife or anti-domestic novels of the counterculture era had the benefit of many such mustache-twirling villains—often selfish and domineering husbands, but plenty of other authority figures as well—all of whom insist that the heroine ought to be docile and fulfilled by her pre-assigned role. The bad guys cite “science” and an established conventional order to back up their claims, but unlike Anna Karenina and Emma Bovary, the discontented housewives of the 1960s and ’70s can glimpse another way of life beyond respectable middle-class wifehood. Other female characters, some of them armed with burgeoning feminist analyses, egg them on and stand waiting to catch them when they jump ship. Their fight wasn’t easy, but in contrast with their predecessors, they had a shot at escape.

The housewife who brings her woes to a therapist’s office today is far more likely to be greeted as Anna Benz is in Hausfrau, by a doctor who asks, “If you are miserable, then why not leave?” Even Anna can’t really answer that question. “I have no knack for volition,” she thinks. She passive-aggressively rebels against her joyless, lonely existence in an unwelcoming foreign land by falling into a series of affairs, which is “wrong in nearly every way but justifiable as it makes me feel better, and for so very long I have felt so very, very bad.” Whatever’s off with her is manifestly pathological and not Society’s Fault. The mad housewife of the 1970s was driven crazy by her inability to stay in the kitchen and let other people run her life; Anna’s dysfunction makes her unable to leave and take charge of herself, much to the exasperation of everyone around her, including the reader. The roots of her paralysis are mysterious—trauma, genetics, fate?—but the tone is glum, and the results are implacably tragic. (Squelching, sadly, any temptation to title the novel Swiss Mrs.)

The Diary of a Mad Housewife, by contrast, was a winning tragicomedy. Part of the pleasure of Kaufman’s novel comes from her sardonic wit, noirishly redolent of Raymond Chandler: Bettina describes an aging socialite as having “skin like a gardenia that’s been in the icebox one day too long.” Nowadays, between Hausfrau and American Housewife, it’s as if someone took an axe to the classic mad housewife novel and severed the humor from the pathos completely. Helen Ellis’ stories are 90 percent shtick of the sort you find in middling TV comedies: Imperious rich women in designer clothes saying bitchy things to each other and the occasional trailer-park trash flourishes for those who prefer to snicker down. “Myrtle Babcock can get her flabby pancake tits out of his face,” one jealous character hisses, as if any actual person would bear such a commedia dell’arte name.

The cover of Ellis’ collection sports an equally artificial image: a young woman wearing black-rimmed hipster-nerd glasses and bright orange panties sitting on a toilet seat, gigantic curlers wrapped in a scarf, as she files her nails. This, like the stories inside, is in the desperate housewife camp along the lines of the ABC prime-time series, where transgression and self-medication are played over the top and strictly for laughs. “I shred cheese. I berate a pickle jar. I pump the salad spinner like a CPR dummy,” rants the narrator of “What I Do All Day.” A large number of Ellis’ protagonists are blocked or otherwise thwarted writers who somehow end up on broadly satirized reality TV shows. (When a writer can’t do as sharp a job of parodying reality TV as TV itself does—cf. the Lifetime channel series UnReal—it’s time to pick another target.)

With few exceptions—a story titled “How to Be a Patron of the Arts,” about a woman with literary aspirations who gets derailed after marrying a rich man, is one—these pieces are oversized gags populated by cartoons, mere slivers of fiction. It’s as if such women can no long support a full-fledged novel, as if it’s impossible to imagine that these women could be happy, but equally impossible to take their unhappiness seriously. “Madam, you are a lady of the house,” a gay editor tells the main character of “How to Be a Patron of the Arts” when she longs for a MacArthur genius grant. “You are a woman of leisure. That is all anyone in their right mind wants to be.” To be so materially lucky that you’re not allowed to experience any discontent at all turns out to be just another way of being swallowed up by your social role.

But the housewife does have one last thing to offer novelists: An opportunity to flaunt their literary technique. The housewife is to the novelist what the still life is to the painter: a subject whose banality will take a back seat to her creator’s display of virtuosity. Flaubert chose to exhibit the apex of his celebrated style, that perfection of French prose, on little Emma Bovary, with her mundane fantasies borrowed from a lower class of novel. At least he had the humility to confess that “Emma Bovary, c’est moi.” For Jenny Offill, a novelist whose brooding, wronged wife and mother in Dept. of Speculation represents some unspecified degree of autobiography (like the novel’s unnamed narrator, Offill took 15 years to publish her second book, years filled with marriage and child-rearing), that’s taken for granted.

Reduced to its premise, Dept. of Speculation sounds like just the sort of book Marlon James deplores—except for the suburban part. A Brooklyn couple (she a writer, he an avant-garde composer), fall in love, get married, have a daughter. The wife works as a creative writing instructor and ghostwriter, but she seems to blame her lack of productivity not on these demanding side jobs but on her family life. In her youth, she posted a sign reading “WORK NOT LOVE!” over her desk and dreamed of being an “art monster … Women almost never become art monsters,” she explains, “because art monsters only concern themselves with art, never mundane things. Nabokov didn’t even fold his own umbrella.” (My postgraduate friends and I used the term art nun, but it’s the same idea at heart.)

Even before the narrator’s husband betrays her, she’s a darkly ruminative sort. Dept. of Speculation comes parceled out a few paragraphs at a time, separated by double spaces, as if the task of making a coherent throughline is just too much for her. It’s a form that typically comes with the assertion that contemporary life is somehow more fractured and miscellaneous than that of the past and calls for innovative narrative strategies. But we can’t really know if that’s true because we don’t know the past as well as we think. We have no idea what living felt like in 1877, when Tolstoy wrote Anna Karenina; we only have the stories people told about it, and it is always a mistake to assume that stories seamlessly reproduce lived experience.

Offill’s style does permit her to juxtapose paragraphs about cosmology or quotations by the likes of Wittgenstein, Rilke, and Simone Weil with passages on domestic life, while stopping short of drawing overt connections between them. Depending on how you look at it, this is either a thrilling way to lend the patina of “seriousness” to the valid but underrated stuff of women’s daily lives or a way of being portentous about trifles without having to cop to it. When Offill’s narrator contemplates her inability to get her daughter to school on time, she “observes the competent mothers who arrive early in a way that suggests both shame and the suggestion that they have nothing more important to occupy their time.” At least she’s being honest about her own contempt, but embedded in those lines is the same disrespect that Dept. of Speculation supposedly dismantles; it’s ruminating about Wittgenstein that lends importance to child-rearing, not vice versa.

Hausfrau—not incidentally, itself a display of exquisite prose—might be the more honest novel on the persistent literary problem of the housewife. Anna’s misery, unvarnished by philosophical or literary allusions, simply is without any particular rhyme or reason. It’s an enigma as eternal as the nature of God and time. Perhaps she’s refusing to acknowledge her own freedom, or perhaps she knows something the rest of us don’t. A lady of the house, a woman of leisure— with all that anyone in their right mind wants—she’s still dissatisfied. So have been many housewives before her, and so are many housewives today. But before we condemn them for their perversity and their tedious complaints, it’s worth remembering this: That’s always been one of the reasons they read so many novels.