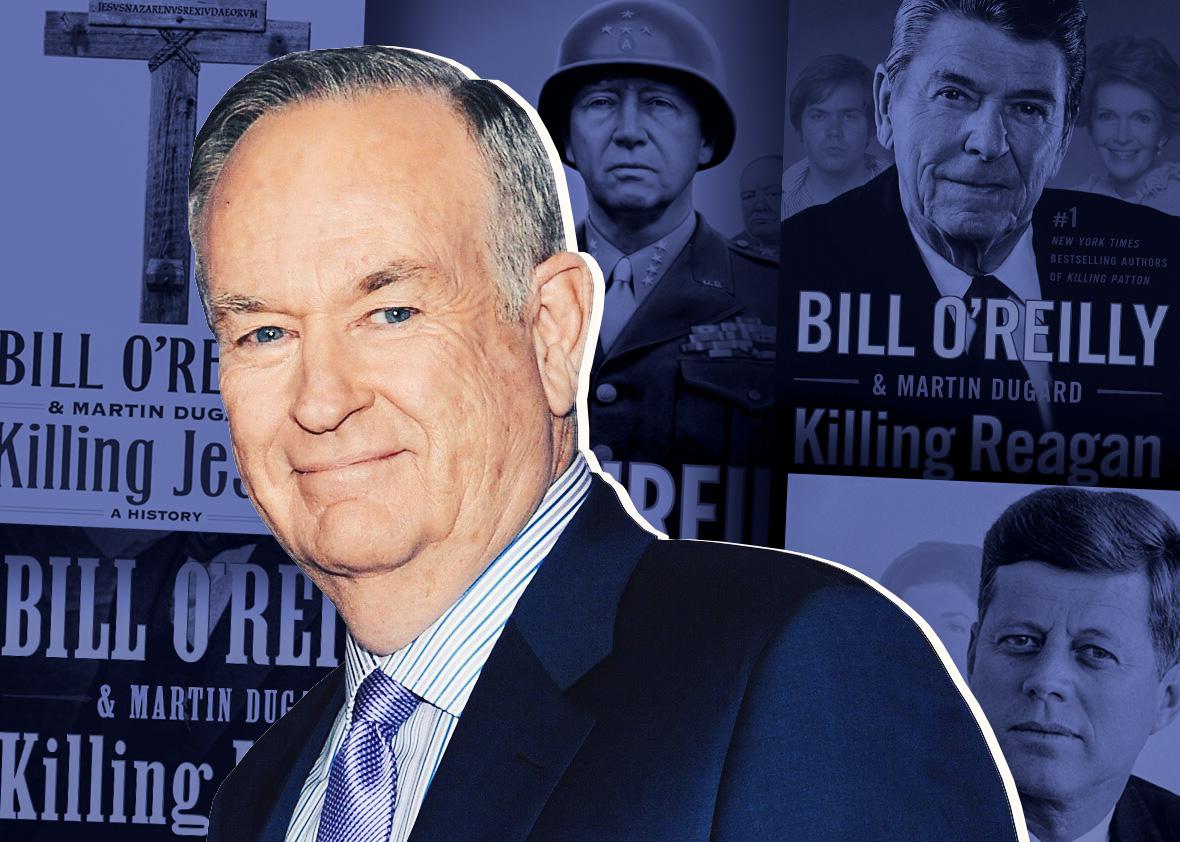

Say what you will about Bill O’Reilly, but he knows what the public wants. This is a guy who hosts a highly rated cable news program and wrote a first novel in which a fiendish stalker murders a man with an iced-tea spoon on Page 6. Nowhere is O’Reilly’s canniness more evident than in the runaway success of his Killing series of popular histories. Beginning with Killing Lincoln, published in 2011, each book—Killing Kennedy, Killing Jesus, and Killing Patton—has sold well over 1 million copies in hardcover alone. The newest, Killing Reagan, published only three months ago, will likely hit the seven-figure mark by the end of the holiday season, as desperate shoppers scramble to find gifts for their cranky, Fox News–addicted dads and uncles.

To churn out five best-sellers in four years, you need a fail-safe formula, like those employed by the kind of thriller impresario who hires other writers to do the heavy lifting on the books published under his brand name. In fact, O’Reilly’s co-author on the Killing series is Martin Dugard, a sometime James Patterson collaborator, most notably on a 2009 title, The Murder of King Tut. The similarity of Tut to the Killing franchise—famous name from history, flimsy insinuations of homicidal conspiracy, florid storytelling—can be no coincidence.

Just how much of the Killing series is actually written by O’Reilly is difficult to discern. The party line is that Dugard gathers the research and O’Reilly does the writing, a dubious assertion given that O’Reilly also hosts a cable news program every weeknight. Yet the books often sound just like O’Reilly—that supercilious defensiveness masquerading as wised-up straight talk—and also occasionally sound like Dugard, the more artful writer of the two. (Dugard has produced several books on his own.) Perhaps Dugard is a literary ventriloquist or perhaps O’Reilly, who boasts of having once taught high school history, really does like to keep his oar in. As a Killing book would no doubt summarize the question, there are secrets here that may never be told.

Until now, the press attention to the Killing books has focused on their lack of historical rigor and their inaccuracy, which is considerable. You can collect errors as you wander through these pages as easily as a child picks up seashells on a beach. This flaw seems to bother the books’ vast readership not a whit. The whole point of the Killing books is that they aren’t like works of real history—that is, dry, slow-moving, and lacking in moral certainty. Books by historians are “boring,” O’Reilly told a radio interviewer, so he figured “if you can write exciting books you would sell a lot of copies and have movies made of them.” This proved to be true: Killing Lincoln, Killing Kennedy, and Killing Jesus have been made into TV movies by the National Geographic Channel, and adaptations of Killing Reagan and Killing Patton are set to air next year.

The Killing books are often said to read like thrillers: short on context and complexity and long on action, crosscutting between multiple storylines, cliff-hangers, and one-sentence paragraphs. Yet the Killing books don’t really resemble any fictional thriller I’ve ever read. They’re Frankenstein productions, with odd and seemingly extraneous bits awkwardly grafted onto the main narrative like a third arm or leg. For example, notably absent from the first 15 chapters of Killing Lincoln, beyond the occasional cameo, is Abraham Lincoln. Part 1 of that book is largely taken up with detailed accounts of the final throes of the Civil War, including battle maps of sites like Petersburg and Sayler’s Creek, complete with curved lines and arrows illustrating troop configurations and movements. For pages and pages, we read about attack formations and left flanks or in one instance a bridge, “made of stone and felled trees” which “stretches a half mile, from the bluff outside Farmville marking the southern shore of the Appomattox River floodplain to the Prince Edward Court House bluff at the opposite end. Twenty 125-foot-tall brick columns support the wooden superstructure.” All of this for an event at which Lincoln was not even present!

This might appear to be a whopping digression in a book that presents itself as a true-crime tick-tock on the Lincoln assassination, but in truth, lavish helpings of military history have become an essential component to the Killing formula. So have maps. By the time you’ve read the first three of the books, a significant chunk of the entertainment value comes from anticipating how the authors will contrive to work all of the obligatory elements into the next installment. General George S. Patton, for example, offers ample opportunities to contemplate the deployment of battalions and the holding of lines. Ronald Reagan, not so much. And so Killing Reagan is reduced to presenting a map of Pacific Palisades, California, with a forlorn dot indicating the location of Reagan’s ranch.

The other key ingredients in a Killing book include, naturally, a persecuted protagonist, who is self-evidently a great man and a great American, or failing that, our Lord and Savior. Preferably, the hero will be surrounded by a couple of other great men, even if they are also his (worthy) opponents. Lincoln has Ulysses S. Grant but also Robert E. Lee; Patton has Erwin Rommel, who like Patton is praised for being “a soldier to the end.”* At least one contemptible naysayer is also a must—the assassin, or would-be assassin, of course, as well as figures like Richard Nixon, who underestimates Reagan, or the snooty Pharisees, who fear that Jesus will endanger their cushy gigs as “arrogant, self-righteous men who love their exalted class status far more than any religious belief system.”

What does it take to be one of Bill O’Reilly’s great men? Well it requires a surprising amount of gazing. In a quintessential passage from Killing Jesus, the authors give us Julius Caesar, lesser men hanging upon his command, poised at the moment before he asserted his imperial ambitions:

The time has come. Caesar stands alone, gazing over to the other side of the Rubicon. His officers huddle a few feet away, awaiting his orders. Torches light their faces and those of Legio XIII. “Alea iacta est,” Caesar says to no one in particular, quoting a line from the Greek playwright Menander: “The die is cast.” Caesar and his legion cross into Italy.*

When not gazing—from windows, over battleship railings, across throngs of worshipful followers—the men of the Killing series are striding. “Lincoln strides forth so the crowd can see him”; “Kennedy strides through the Oval Office doors.” Language that initially seems merely hokey only becomes more savory as one’s connoisseurship of the Killing series grows.

Every Killing book is written in the present tense, that lazy writer’s bid for breathless immediacy. Each indulges frequently in the series’ signature rhetorical flourish: “The man who has X hours/days/years to live” … “is anxious/is pacing/admires Greta Garbo as she takes off her shoes and lies down atop the mattress in the Lincoln Bedroom.” This device has lost a lot of its oracular oomph by the time you get to Killing Reagan, which begins, “The man with 24 years to live steps onstage.” (Reagan’s life seems to have given the authors the most trouble in fitting it to the Killing formula, not least because nobody killed him.)

A general miasma of superstition and portentousness swathes the Killing books. This ranges from the prophetic dreams of victims (Lincoln) or their wives (Calpurnia) to that hoary list of parallels between the Lincoln and Kennedy assassinations to more blunt foreshadowing along the lines of “little did he realize that the battleship he rode past that morning would soon be transporting his corpse.” The authors’ position on such mumbo jumbo is curiously inconsistent. Both Dugard and O’Reilly profess to be Roman Catholics, and by doctrine they ought to eschew secular signs and omens. They do disparage Ronald and (especially) Nancy Reagan for relying on “fortune tellers” like the astrologer Joan Quigley. Yet their admiration for Patton is undiminished by his paganish conviction that he was the reincarnation of Hannibal of Carthage.

Consistency, however, is the hobgoblin of less grandiose minds than Bill O’Reilly’s. As Nicholas Lemann once pointed out in the New Yorker, O’Reilly is less a conservative than a populist. The beliefs he professes form a loose conglomeration of conventional and sometimes contradictory pieties driven by emotion and held together by the force of his aggressive personality. Class resentment is his bedrock, but while the Killing series presents its heroes as men of the people—the wealthy Kennedy gets a pass on account of being Irish and distantly related to O’Reilly—they are certainly not humble (except for Jesus). “Old Blood and Guts” Patton, by all appearances O’Reilly’s ideal man, is, we’re told, “fond of the finer things in life.” The eyebrow raised at Caesar’s Spartan consumption of food and drink eases down again as the authors contemplate his robust appetite for sex. Men have needs, is one overarching philosophy of the Killing series, and real men need women to slake those needs.

When it comes to sex, the Killing series engages in a certain amount of fogeyish titillation. Mistresses are trophies, either “voluptuous” and “bosomy” or ballerinas and former fashion models. Cleopatra presents herself to Caesar in a transparent white linen shift. All of this is told with the meaty zest of the kind of early ’60s men’s magazine you might find stashed away in a Wichita insurance salesman’s rumpus room.

The authors reserve their greatest fervor, however, for voyeuristic depictions of the perverted shenanigans of the books’ villains. Of particular interest in Killing Jesus is the Roman emperor Tiberius, described as a pockmarked, Jabba the Hutt figure who stocks his villa with underage captives who are forced to cavort lewdly before being thrown off a cliff. O’Reilly’s longstanding horrified fascination with pedophiles and other sex criminals—a frequent theme on his TV show—finds luscious nourishment here, as he lingers, with a mixture of moral outrage and real-estate envy, over Tiberius’ “sprawling palace with its marble floors, erotic statues, works of art, and stunning views of the Mediterranean Sea far below.”

But in truth pleasure concerns the authors of the Killing books far, far less than pain and gore. O’Reilly, the one-time rookie novelist who found such ingenious use for that iced-tea spoon, has not lost his macabre touch. There’s a lot of killing in the Killing books, whose pages are littered with broken and tormented bodies. If, say, you’re looking for a lovingly detailed account of how Hitler executed the Nazi officers implicated in the failed plot to assassinate him (and who isn’t?), then you’ve come to the right place. Killing Patton reports that the protracted hangings inflicted on the Operation Valkyrie conspirators, filmed and engineered for “maximum embarrassment,” assured that “the accused had plenty of time to memorize the interior of the room: the whitewashed walls, the cognac bottle on the simple wooden table, the door through which he entered alive and would exit quite dead.” (The cognac, and the “quite dead,” are nice Bond-villain touches.)

Then there’s Patton himself, paralyzed from the neck down after the automobile accident that would ultimately claim his life: “His face is gaunt from weight loss, and there are open holes in his cheekbones where doctors drilled into his face to insert steel fish hooks to hold his head in traction.” Or the doctor at Ford’s Theater who had to keep sticking his finger into the bullet hole in Lincoln’s skull to relieve the pressure of the blood on the dying man’s brain. Although Jesus, sadly, engaged in no military exploits—compelling the authors to devote all those Killing Jesus pages to the gazing and battling of Caesar, who died 44 years before Jesus was born—the Lamb of God, fortunately, lived in an age of spectacularly brutal executions, the most gruesome of which get explicitly recounted by O’Reilly and Dugard.

What you won’t find in the Killing series, however, is much in the way of conventional politics. Even Killing Reagan, about a man who did little else of note, focuses more on Reagan’s symbolic leadership—enabling Americans to feel national pride again, etc.—than his policies. Jesus does get portrayed as a first-century anti-tax activist, and Killing Patton takes pains to inform its readers that Stalin “did not believe in Christmas.” But such O’Reilly Factor moments are rare, and the authors even find it in their hearts to admire FDR’s “drastic experiments in government,” defending him from accusations of Communist leanings, despite his “foppish behavior.”

The most strikingly persistent theme throughout all of the Killing books is unexpected: the physical vulnerability of “important people,” who, despite being valiant and powerful white men (or Margaret Thatcher), are still tragically subject to their own failing flesh. No matter their greatness, or how resolutely they set out to fulfill their destinies, or the daunting challenges they have surmounted, their triumphs will tempt vile enemies to try to assassinate them, enemies who will sometimes succeed. But even more implacable are the bad backs, the crippled legs, the tremors, the weakening bladders and, in the case of both Reagan and Thatcher, the slow erosion of the brain itself. The very grandeur that makes us admire these titans causes them to suffer bodily limitations more keenly than the rest of us. Such is the special burden of greatness, a burden O’Reilly understands all too well.

The authors rarely fail to introduce a significant historical figure without going on to list his ailments. Public appearances elicit discussions of how easily a sniper might have picked off a president or a general—even when one didn’t. A car crash takes out Old Blood and Guts, and despite some feeble hinting around that Stalin might have been behind it, the more terrifying reality is that even the “general whom Nazi Germany feared more than any other, the former Olympic pentathlete, the cavalry officer who once hunted the infamous Pancho Villa across the desert plains of Mexico, and the warrior who publicly stated that he wanted one day to be killed ‘by the last bullet, in the last battle, of the last war,’ ” got erased by a couple of drunken, joyriding GIs from his own side.

Perhaps this preoccupation isn’t so surprising, given that the median age of Fox News viewers—the targets of so many of these freshly wrapped books this coming Christmas—is over 68. They’re at the age when hips give way and blood pressure inexplicably soars. But it’s more than that. Stick around on this planet long enough, and you come to recognize the arbitrary nature of fate. Letting your high-strung wife persuade you to take in a theatrical rom-com instead of the Arabian Nights extravaganza you’d prefer to see could just be the decision that puts you in reach of a preening, delusional matinee idol toting a single-shot, 5.87-inch derringer. Sooner or later your luck runs out. It’s enough to make anyone want to stay home with a good book.

Correction, Dec. 17, 2015: This article originally misidentified Erwin Rommel as Erich Rommel. (Return.)

Correction, Dec. 18, 2015: This article originally misspelled the name of the Greek playwright Menander. (Return.)

—

Killing Lincoln, Killing Kennedy, Killing Jesus, Killing Patton, and Killing Reagan by Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard. Henry Holt.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.