This year marks the 20th anniversary of Philip Pullman’s The Golden Compass, the first novel in the His Dark Materials trilogy, which also includes The Subtle Knife and The Amber Spyglass. The Golden Compass is a “true classic,” not least because it is true in the classical sense—pure; well-made; its needle sweeping across the old, best themes: childhood, knowledge, belief, and love.

Well, Slate may not be wholly impartial when it comes to this author’s work. (At least one editor here has a first-born named Lyra.) But with Random House’s huge, beautiful anniversary copy in hand, we tried to keep our cool as we spoke to Pullman about the “young adult” literature label, his status as a “post-Romantic,” and the long-awaited companion piece to His Dark Materials: The Book of Dust.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

We talk a lot about “young adult fiction” and who reads it and why. Is The Golden Compass young adult fiction? What makes young adult fiction different from regular adult fiction?

It’s a very complicated question. I don’t know whether [The Golden Compass] is a young adult book or children’s book or adult book that somehow sneaked its way into a children’s bookstore. I don’t actually think about the audience. I don’t think about my readers at all. I think about the story I’m writing and whether I’m writing it clearly enough to please me. If you asked what sort of audience I would like, I would say a mixed one, please. Children keep your attention on the story because you want to tell it so clearly that nobody wishes to stop listening. And the adults remind you not to patronize or underestimate the intelligence of the children.

You’ve said you’re not a huge admirer of C.S. Lewis or J.R.R. Tolkien, both of whom have written fantasies that in some ways resemble The Golden Compass. Is it fair to say those books have a somewhat didactic relationship to readers?

They’re often bracketed together, Tolkien and Lewis, which I suppose is fair because they were great friends—both Oxford writers and scholars, both Christians. Tolkien’s work has very little of interest in it to a reader of literature, in my opinion. When I think of literature—Dickens, George Eliot, Joseph Conrad—the great novelists found their subject matter in human nature, emotion, in the ways we relate to each other. If that’s what Tolkien’s up to, he’s left out half of it. The books are wholly male-oriented. The entire question of sexual relationships is omitted.

Tolkien was Catholic, which meant that for him, there were no questions about religion. The church had all the answers. But Lewis was different. He was a Protestant, an Irish Protestant at that, from a tradition of arguing with God and wrestling with morality. His work is not frivolous in the way that Tolkien is frivolous, though it seems odd to call a novel of great intricacy and enormous popularity frivolous. I just don’t like the conclusions Lewis comes to, after all that analysis, the way he shuts children out from heaven, or whatever it is, on the grounds that the one girl is interested in boys. She’s a teenager! Ah, it’s terrible: Sex—can’t have that. And yet I respect Lewis more than I do Tolkien.

To move on to someone you seem to respect quite a bit—Milton—there are so many parallels between The Golden Compass and Paradise Lost. Lord Asriel must be Satan, right, with his starry name and ambition and dark magnetism. And then there are all the Miltonic similes in the bear fight, and the witches sometimes playing the role of the angels. What other Miltonic Easter eggs should we look out for? Do you have a favorite one?

Well, the Dark Materials is of course a retelling of the Miltonic temptation and fall, but most of that happens after The Golden Compass ends. And what I wanted to do was represent the fall as entirely good. It is good for people to know things, to grow up, to become sexual beings.

How conscious of Milton and that story were you when you were actually writing?

It wasn’t on a sentence-to-sentence basis. But you mentioned the Miltonic similes, and those were deliberate allusions. The epic context demanded that there be a certain epic quality to the language. I didn’t get too close to Milton, though, and there was never a moment in the writing process where I felt, “I’ve got that wrong. Oh dear, I’d better change it.” It is my story, and I will do what I want with it. I remember the words of William Blake: “I must create my own system or be enslaved by another man’s.”

But Blake, his Songs of Innocence and Experience, are all over His Dark Materials. And so is Wordsworth’s idea of “abundant recompense” for the lost innocence of childhood. And the Northern Sublime, when Lyra goes to rescue Roger—that’s out of Frankenstein. Would you call yourself a Romantic author, 150 years later?

Well, I suppose that would be a fair description. I reveled in and loved the Romantic poets—Keats, Shelley, Coleridge—and Romantic music, too. The music of Beethoven, Wagner. All of the cultural poets of that time are very close to me. So I suppose I could be a Romantic poet: post-Romantic or imitation-Romantic, if you like.

The descriptions of the North—those are out of Book 2 of Paradise Lost, and my imagination, and other books I’ve read. I’ve never been to the Arctic. Milton never went to hell either.

But I should say that my other connection to that story, the temptation and fall, is that I grew up as a Christian in the Christian tradition. It was in the ’60s—right before there were really big changes in the language of the liturgy: a new English Bible, new forms of Anglican worship. Well, I missed all of those. The language that surrounded me in the church was the language that had been used for 400 years. I found myself very much a part of that particular history, those hymns and those words and prayers, that specific phraseology. It was my inheritance. I don’t believe in it any more. But I love churches, going into churches, listening to the language. It will never leave me.

What’s your favorite parable?

I think the Good Samaritan is probably the best. It is so clearly told, so simply conceived, that having heard it once you’ll never forget it. Jesus, like so many of the preachers wandering Galilee, was a tremendous storyteller. He wielded words and images with enormous genius. “When you see a speck in your brother’s eye and pay no attention to the plank in your eye”—that is just a wonderful image, and so true. I wonder what would’ve happened if he hadn’t been arrested and executed. Would he have gone on and written a book? We know he can write because we have a description of him writing in the dust …

Perhaps he would have written a Book of Dust.

It’s possible!

One thing I noticed rereading The Golden Compass was how often Lyra reflects on whether she’s alone. She’s so grateful she’s got Pan; she pities Iorek for not having a daemon. And it seems that, in a theological allegory, the question of loneliness—the soul as your companion, God as your companion—is pretty important. Can you talk about loneliness?

You’ve touched on something that is very crucial to my conception of the book, because when I was beginning to write it, Lyra did not have a daemon. She was alone. It was hard to write because what I really needed was someone for her to talk to. It was a technical problem. And when I realized that she had a daemon, that she wasn’t alone, it suddenly became much easier.

But the question of how she felt—when Lyra first meets Iorek, she feels profound pity for him, on account of what she assumes to be his loneliness. But then she comes to realize that he’s not human, he can do all these things, he’s a bear, he’s different. Perhaps his armor is his daemon. Perhaps he has no need of a daemon. The relationship between the person and the daemon is a very interesting, intricate, and profound one.

It’s like that party game that everyone plays: If you were an animal, what animal would you be? If you were a pop song, which pop song …

Yes, except you can’t choose your daemon. You have to see who it turns out to be.

Why is the daemon idea so seductive?

I think we all really like animals! We would all like to have spirit companions. It may be as simple as that. I can’t remember how the notion came to me except that it just sort of appeared, but it wasn’t just having daemons that was important; the important thing—the key to the whole story—was realizing that children’s daemons changed. They take their final form when the children come into adulthood, into some sort of adolescence. That was the big key to the whole story because I realized, then, that the book was about innocence and experience. The transition in the human form from one to the other.

When you’re a teenager, there are different ways of being, different personalities you try on. You want to be like all the other boys and girls in the group. And you also want to be distinctive in some way—to be yourself, to express your own personal form. So the daemon reflects those contradictions for a time. Then, it takes its shape. That’s the “abundant recompense”—that’s when you settle into yourself.

Lyra is so extraordinary—she’s fierce and determined and willful. And you wrote her before books like The Hunger Games or Divergent brought girls like her into vogue.

I didn’t do it for any sort of political reason. I didn’t look around and think, “Oh, we really need a story about a strong-willed young girl.” Lyra was the personality that came to me. She was simply the way she was. And she was the one who dictated things.

What drew you to her?

Her personality. The fact that she was so strong, so individual. But she’s not—I like to stress this to people—an unusual child. She’s very ordinary. I was a teacher, I used to teach girls her age, and there were many Lyras. Many Wills too.

You say she’s a wonderful liar with a poor imagination.

Yes.

Her epithet is Lyra Silvertongue. In a retelling of the Garden of Eden story ,..

The story is about a particular person. She is a person who I hope is alive, who can grow and develop. There’s only so much to say about the theology; I think the story is more about children at that age and how they grow up and change. It’s a great thing, growing up. It’s a great thing to become interested in big questions like why we’re here, what’s the purpose of everything. But along with that comes a sense of lostness and doubt, and at significant times there is more or less doubt, more or less knowledge. To me the process is an extraordinary thing.

Is that fascination why so much of your fiction takes place in Oxford College?

There are a number of writers of books for children who’ve written books in Oxford, or have put Oxford in their books. I think that’s a tribute to Oxford. The setting does have a certain hold on me. Maybe it’s the veils of mist that come off the river and dissolve reality …

I am going to try to pierce one veil right now. What can you tell us about The Book of Dust?

I will tell you … that I am writing it. OK, I’ll tell you it’s about Lyra—Lyra at a different stage in her life. It’s not a prequel or sequel. It will be a companion novel, if you will, to His Dark Materials, though that story is finished. As I go, I’m discovering things all the time about Lyra, about daemons, about dust, about the whole universe. It’s exciting for me.

With 20 years of hindsight, is there anything you would’ve done differently if you were rewriting His Dark Materials?

No. Those works are complete. Actually, I wouldn’t change the first two; with The Amber Spyglass, I would perhaps have liked to take another sixth months. But so many people were writing me and begging me: “Hurry up! Hurry up!” I don’t feel that it is a bad book, though. I’m happy with it.

Have you seen the comic book version of The Golden Compass?

Yes! I love it because the illustrator, Clément Oubrerie, is an artist whom I greatly admire. I’ve liked him long before I knew that he would be working on my books.

It’s interesting—the style is kind of sketchy, and you get a sense of Lyra’s scrappiness.

Exactly. It looks like he did it in a hurry. I like that. He has such command of his pen—he can do all manner of different expressions on people’s faces. And it’s not quite like I imagined it, but that doesn’t matter.

His Dark Materials will become a TV series! How do you feel about that?

Very pleased indeed. I believe the greater length and time is necessary for the story to stretch its wings.

Do you anticipate doing a lot of consulting on the project?

I’m an executive producer! And I have no idea what that means. But I will be consulting—of course I will. I’m very excited.

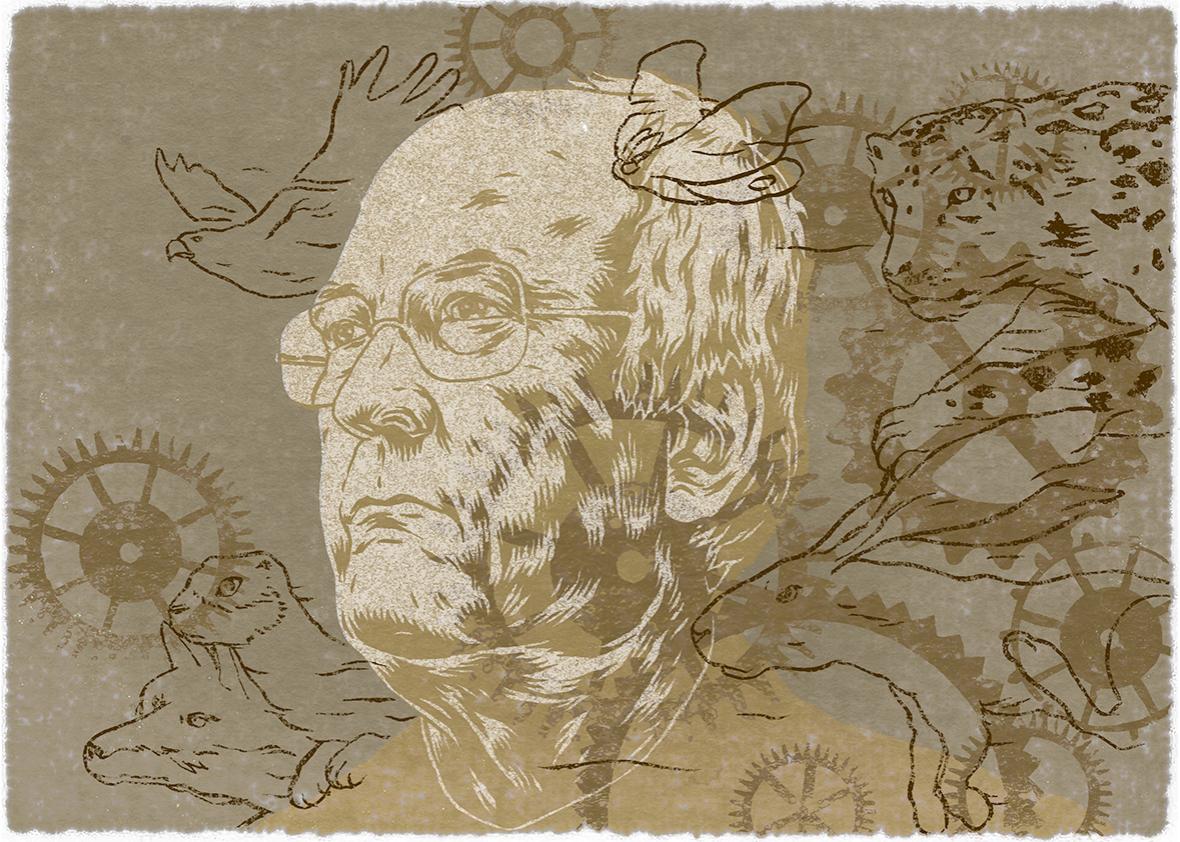

I have to ask: What form does your daemon take?

I can only imagine that she is a bird of the crow or raven family. Maybe a magpie. She digs around for shiny, bright things and steals them.

Like lines or images from other books?

Oh, perhaps! Every writer I’ve ever enjoyed, I’ve stolen something from—I’ve stolen things from writers I didn’t enjoy if they had a good turn of phrase or an interesting idea. But let me see: I love the old English ballads, their swiftness and power. They are so simple and so immediate. And of course, Milton’s way with language is very forceful and striking.

But the thing about ravens is that it doesn’t matter whether it’s a piece of aluminum foil or a piece of diamond. That’s how it is with storytellers. If it shines, if it sparkles, we want it.

—

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.