“Beauty that does not disguise the wound,” Mark Doty writes in Deep Lane, his ninth book of poems, “but reads through to the lack it marks.” It’s the opening of “Ars Poetica: 14th Street Gym,” a short, graceful poem, just 10 four-beat lines, in which Doty describes a one-armed man doing chin-ups and the tattoo covering (but not obscuring) the joint where there is no arm.

The poem is, in many ways, characteristic, a clear argument carried forward by fluid narrative momentum, and that momentum paced by interruptions that let different tones intrude, as in the concluding lines: “so I’ll notice / (what you can’t restore, inscribe) // the blue wing needled on the socket.” Doty, who has won the National Book Award and the T.S. Eliot Prize for his poetry, as well as being a best-selling memoirist, is an unusually generous poet, and he writes with a rare mix of abundance and clarity. If his poems are accessible (and they are, even if that term matters too much to too many), they are also bountiful, arched toward beauty in a desire for solace.

As in “Ars Poetica,” Doty doesn’t hide from suffering—of which he’s known more than his share. He came to national and international prominence in 1993 with My Alexandria, a gorgeous and shattering book threaded with the devastation of the AIDS epidemic, in particular the encroaching death of his partner, Wally Roberts. According to an interview with the Guardian, he wrote this new book in the aftermath of a failed marriage, at a time when “I began to understand that I was in no way done with the grief I had been carrying around from the early 90s when an awful lot of people I knew died.” He’d also begun abusing drugs, and Deep Lane recalls the ghost (almost literally: there are several ghosts in the book, including hers) of his mother’s alcoholism.

But if Doty doesn’t disguise the wound, he does, increasingly, seek to transfigure it. I have always been wary of poems that seem to wish me well, and there are moments in Deep Lane where I find myself on alert, feeling his rich inventiveness relent for a moment as he leans toward a kind of ready-made comfort: “Endless gratitude / for the thing I would without be no one I know,” “entering into the never- / to-be-repeated,” “a measure of pain makes joy real.” Lines like these mark the far side of a seeming kindness in Doty’s work—an elsewhere-appealing wish to reward his audience, one that I also hear in poems that feel ideal for public readings, such as “Ithaca,” a sharp and witty piece so clear and continuous in its swervings that I can easily imagine a large room responding with delight when he finishes. The poem begins with a bright contrast, between himself and his ex, laid out playfully:

My ex adores the age of mechanical reproduction;

nearly every day he copies something he likes,

simply to add more beauty to the world.

Fifteen lines later, the poem concludes, having shifted its allusions from Walter Benjamin back into Homer and then forward through Robert Lowell. (The book is scattered with allusions to, echoes of, and meditations on poets and painters past; Doty seems to stand confidently in a legacy of enduring artists.) Its final lines are both playful and poignant:

Ithaca so over the long winter it can’t hold

its shaggy head up anymore. Ruinous old century,

spilling into this one: liquor and lopped trees, sharp odors

of ice and gasoline. What are these Ithacas for? Century of my birth,

go to sleep now. Can’t we be done with you.

Though I admire “Ithaca,” there are poems here that matter more to me, poems in which Doty’s considerable talent and remarkable grace struggle to redeem the situations they describe. That drama is evident in the first poem, one of nine that shares the book’s title. Doty is a master of naming: He frequently delivers that surprising immediacy that comes from precisely articulating something familiar in unfamiliar terms. “What descriptions—or good ones, anyway—actually describe … is consciousness,” he claims in his wonderful and welcoming book of criticism, The Art of Description. The mind that comes through here seems restless in the face of beauty that roots down in the dark earth and blooms in despair. He opens, echoing Gerard Manley Hopkins (as he often does in Deep Lane):

When I’m down on my knees pulling up wild mustard

by the roots before it sets seed, hauling the old ferns

further into the shade, I’m talking to the anvil of darkness:

break-table, slab no blow could dent

rung with the making, and out of that chop and rot

comes the fresh surf of the lupines.

You can hear the heavy restlessness in these lines, which are just one sentence, which keep adding, renaming, stretching syntax so that “slab no blow could dent / rung with the making” sounds almost like a Homeric epithet. You can hear it, too, in the counterweight of those dense rhythms and the alliteration that tangles phrases like vines. The poem is, according to the Guardian interview, “about a friend who had killed herself,” though it mostly keeps that knowledge to itself, continuing instead to dig: “Spade-plunge / and trowel, sweet turned-down gas flame / slow-charring carbon.” “Beauty’s the least of it,” he writes, before finally mentioning the friend, out in a garden of her own: “you get ready, // like Deborah, who used to garden in the dark.”

In these poems, I, as a reader, feel less present, less anticipated—more of a bystander as Doty chases, through language, that which resists our terms. The poems still move forward with incredible ease; Doty is the rare extraordinary poet whose books I can read in just a few sittings. But they are, in some sense, more convincing, because they are more apparently consumed by their own private purpose. In another of the book’s poems titled “Deep Lane”, Doty writes about a fish that had come to seem “individual,” mostly through the seeming will that drove its endurance:

Seems to want,

seems to feel. But as we knew him,

semblance fell away: We felt the presence

of the soul of him, if soul could be

understood as specificity,

so that when he himself was swallowed

—white appetite perched on the roof,

bill raised to the air, throat unrelenting—

the absence in the pond grew resonant,

a sort of empty ringing.

Though he doesn’t say so, Doty seems to be recollecting a “we” made up of himself and his ex-husband, and the echo of that double-consciousness, since foreclosed, causes its own “empty ringing,” even as the poem continues to move. I’m especially taken with the sudden shifts of style and focus—from the abrupt braking of “seems” to the more fluid “semblance” that fades, from specific fishy soul to the unnamed bird rendered as “white appetite,” the shifting grammar that composes the separate sentence fragments here—that feel like the mind at work, looking for new angles of vision and thought.

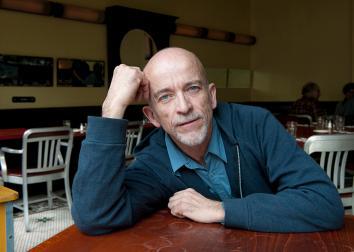

Photo by Dimitris Yeros

In The Art of Description, Doty spends a relatively long time on the English language’s most famous fish poem—Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Fish.” Late in that chapter, he observes of writing about animals, “Consciousness can’t be taken for granted when there are, plainly, varieties of awareness.” Reading a poem like the one above, I feel, in its banking attention, that consciousness has not been taken for granted. The encounter with presence, including the layered presence of absences (of the fish, of the former husband), seems to call the mind out toward its own farthest reaches. There’s a quickening there, a counterlife—and though the poem ends in despair (“How can I take any pleasure in this garden?”), the grief doesn’t overwrite that fullness any more than the consolations of other poems negate their grief.

The book’s final title poem refers to “Dark kindness / woven in the fabric of the afternoon.” Doty goes on from there, addressing himself at arm’s length:

And because you’ve held within your own veins

another passage of fire—obliterating mercy—

not these lit-up leaf clouds

but a hot wire stealing into

the deepest chambers of the night—

you love the way the asphalt lifts

then hurries down toward Deep Lane.

A bit of the prefabricated understanding creeps back in after that: reminders of the singularity of experience and the way that encourages us to cherish experience. Nothing untrue, but it feels a little thin. Soon enough, though, the poem enlarges and turns narrative, a pleasant confusion of past and present that moves decisively into the past in the poem’s last two stanzas:

Every night a little like the one he came home late,

happy, from the leather bar, and you in your welling up

out of sleep said, I have a lake in me,

and he looked at you closely, with a generous,

unflinching scrutiny, undeceived, loving, as clear a gaze

as anyone had ever brought to you, and he said, You do.

It’s an extraordinary moment: The second-person address that Doty has been using to speak of himself is taken over in the poem’s final words, becoming a gift from without. It’s also a striking companion to the goal, from “Ars Poetica,” of “Beauty that does not disguise the wound.” That “generous / unflinching scrutiny” that he then renames as both “undeceived” and “loving”—the two seem inseparable here—ends in a statement that, barring some equivocation, is wildly untrue. The statement’s not meant to deceive, but it is meant to be habitable, in the way that the past, though gone, remains habitable.

The world of these poems does not always seem kind, but it does seem habitable. There’s a wonderful longish poem here about a deer that Doty used to see on Fire Island, one that was missing one hoof. It’s a masterpiece of description, including these lines, in which a “generous / unflinching scrutiny” is audible, along with the awareness that such scrutiny cannot fill the absence it regards:

And ticks; he wore a small crown

of swollen passengers

between his two brave ears,

where he could not bite them,

and no other deer provided

the seemingly secret grooming

they perform. He exhaled a small puff

of carrot-scented wind….

A little later, he remembers feeding it:

Then he’d take his tongue to my hands.

They startled me at first, those sucking lips

around my fingertips, careful,

as if he were grooming another

of his kind.

The different kinds of being (and the “as if” that stands between them) drawing us out, toward kindness, in both senses of the word: kinship, charity—so often, reading these poems, I’ve felt myself in the presence of just that.

—

Deep Lane by Mark Doty. Norton.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.