More than a century and a half ago, newlyweds Nathaniel and Sophia Hawthorne scratched a love message to each other into the window of their cottage with Sophia’s diamond ring. “Man’s accidents are God’s purposes,” they etched into the pane. “April 3, 1843. In the Gold light.” Those were the days, writes Matthew Battles in his new book, Palimpsest: A History of the Written World, when “writing leapt beyond the page”—when letters were “carved in wood or punched and chased in silver, embroidered in tapestry and needlepoint, wrought in iron and worked into paintings, a world in which words [were] things.”

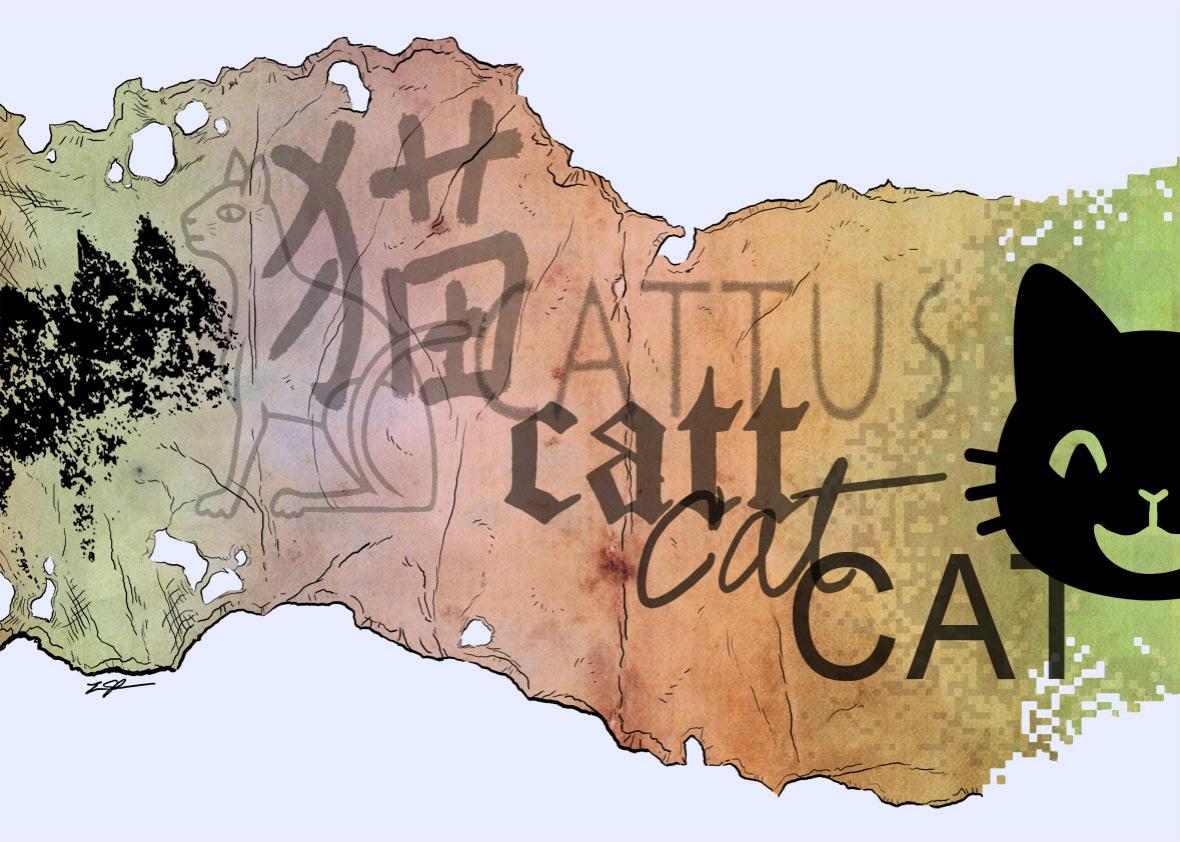

Based on Palimpsest’s subtitle, you might reasonably expect the book to recount how Egyptian hieroglyphics were decoded, or who created the first alphabet and why, or the history of punctuation marks. But Battles, who researches the relationship between technology and the humanities at Harvard University, is not concerned with highlighting the traditional bullet points in the history of writing systems. Instead, this book is a history of something more abstract—of our relationship to writing.

Palimpsest’s chronology is linear but consists of a series of mostly lesser-known stories about writing. We learn about the invention of Chinese writing, Ezra Pound’s fascination with the intricacies of the written word, and Jesus’ ambivalent relationship to it. There’s an analysis of computer code as “writing that writes,” in that it is a kind of writing that often serves to generate more writing. We are in the company of a man of letters sharing an artistic, rather than historical, take on what it means to capture language on the page in symbols.

Battles’ artistic perspective in fact yields a rather eccentric historical interpretation, which hinges on a certain confusion as to what writing actually is. His vision of 19th-century Western societies is one in which the place of writing was “collective, aphoristic, and descriptive rather than individualistic, lyric, and voice-centered.” Couples like the Hawthornes were scratching their sentiments onto windowpanes; graffiti on every second wall proclaimed the common person’s feelings; one commemorated occasions with embroidered messages; public buildings were decorated with sonorous inscriptions. He argues that, after this period, writing was sadly corralled into “the private page and the commercial space”—the idea being that today, we write primarily in contained spaces such as the page, be it physical or digital, and that while we may feel surrounded in public spaces by writing such as billboards and signs, most of this is in the form of advertisement.

But is the place of writing in our world really different from its place in Charles Dickens’ in the exact way Battles thinks it was? Today, many modern people walk around “writing” all day via tweets, clearly not confined to private pages and ads. Battles even at one point praises Facebook as a modern equivalent of the walls upon which Pompeii residents scrawled their japes and doggerel. But surely we wouldn’t classify Facebook as a “commercial” space on a technicality, compared with those walls in Italy. Much of the “collective, aphoristic” writing Battles describes would today be termed tweets and posts.

Also eccentric is Battles’ idea—related to his belief that writing played a more vivid role in human lives in the past than now—that writing is often more “alive” than speech. Battles discusses the well-known irony that Plato distrusted writing for threatening to weaken memory and that Rousseau believed that writing tamed the warm, empathetic nature of speech into chilly regimentation.

But Battles argues that the difference between humanity pre- and post-writing has been exaggerated. For him, to the extent that Plato and Rousseau had a point, they were identifying that writing can be but one of many manifestations of power—i.e. depriving people of active engagement with ideas by storing information on the page (Plato) or tamping down basic human passions (Rousseau). Yet writing is just one of many possible manifestations of power, and preliterate humans were obviously quite familiar with others. So the past wasn’t really that unlike the present, he believes. And the present isn’t that unlike the past, either—“What is essentially wild about the human species,” Battles writes, “may be expressed as well in writing as in hunting or sleeping or migration. There is no noble savagery for which to atavistically pine, any more than there is some ignoble savagery from which we escaped.”

Thus, for Battles, writing is less a taming of speech than a reshuffling of the deck chairs—writing does everything that speech used to. If writing can be used to rule and regiment, then we must remember that the Neolithic Revolution happened without writing. And in the same way, writing can be the same jolly, communal heart to heart that speech can be: “So the great chain of alphabetical evolution collapses in a welter of characters, glyphs, and symbols mingling in friendly, familial, and even erotic enthusiasms of conversant meaning.”

Neat idea, but it ends up being tricky to apply. On the narrative vagaries and contradictions of the Bible, Battles proposes that these constitute “a community of signs interacting in ceaseless combinatorial flux, presaging possible futures, shuffling useful pasts, rhyming hope with history.” That is nicely put, but philologically approximate, if the Bible is meant here as a true example of writing. The Bible is an orally based text, composed of what began as narratives that varied in their telling according to narrator, region, and era, as all oral narrative does. The reason Genesis contains two different creation stories and Moses’ father-in-law is presented with three different names is not “combinatorial flux” in a sense that qualifies as artistic—even in the communal sense—or “literary.” The Bible simply consists of oral storytelling that happened to be set into writing at a certain point by people unfamiliar with the linear, rigidly empirical mindset that was later created by the stringencies of formal writing.

Courtesy of Matthew Battles

Here, and in his idea that people before our time were immersed in the written word more than we are, Battles loses sight of this difference between written speech and formal writing. John Milton did not intend his elaborately phrased Areopagitica, an argument about free speech that Battles quotes, as a salutational “interactive” yelp into the public forum, but as a magisterial statement. In other words, both the graffiti in Pompeii and today’s Facebook posts are less writing than written speech: Understanding the difference shows that now is less unlike then than we might suppose.

One thing that stands out about Palimpsest is that it is a book about writing that is written beautifully. Rather willfully so, at times—the book is less pedagogic than consciously literary—but the vivid prose was what kept me reading as much as the content. As Battles says of Chinese characters: “They seem like visual insularities of expression, pictures of things, at once closer to meaning’s bone and more alien to the flickering, warm life world of language itself.” This is lovely, if slightly overdone, prose, at times recalling F. Scott Fitzgerald. One imagines Battles composing it in longhand in roughly 1923, later typing it up on an Underwood manual.

Fortunately, Battles explores the elusiveness of meaning without embracing meaninglessness as the essence of the human condition. “One person’s picture, one person’s truth, is never wholly that of another; each of us stands beside our own word in witness or advocacy,” he notes—and many will know where this kind of observation often leads. However, the two Jacques, Derrida and Lacan, and their poststructuralist creed only come up in passing—Battles delights in the actual human experience, not recreational abstraction.

But his almost anthropomorphic conception of writing will be difficult for most to square with the reality most of us live in, I suspect. “It’s as if letters have the need to be read, to find their way into the minds their forebears prepared for them—and to prepare those minds for future letters as well,” he writes. I’m not sure I quite understand that: Compared with chatting, writing—the formal kind, at least—is so very authoritative and static. Its air of permanence is what makes us so uncomfortable when we hear our language changing, and is why we tend to think of “language” itself as writing rather than speech.

Battles sees the written word as more of an organism than a thing: “Into the forests and dark waters of myth and memory intrude the letters, those subtle conductors, cobbling together colleges and choruses of thought.” That will resonate for most, though, as a description better suited to status updates and Gchat windows than to that other, mustier form of writing: carefully composed prose.

—

Palimpsest: A History of the Written Word by Matthew Battles. W.W. Norton and Company.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.