“Behold us nearly here, coming down the long path,” Clarice Lispector writes in the story “The Burned Sinner and the Harmonious Angels.” “An angel’s fall is a direction.” For almost all of New Directions’ remarkable new Complete Stories, brilliantly translated by Katrina Dodson, I felt wrapped in flame. I might as well have been burning up on re-entry trying to follow strange angels, receiving ecstatic signals, sometimes from afar and sometimes very near.

Lispector is an iconic figure in Brazil, where her work is taught in schools and her persona has become larger than life. A Ukrainian Jew transplanted to Brazil who also spent many years in the United States and England, Lispector was influenced by mystical elements of Judaism but also by living within a certain strata of society. Perhaps because of the patriarchies we live within, Lispector is known for writing spectacularly well about the lives of women at various stages of their lives.

But, like most enduring writers, Lispector, who died in 1977, was more than one thing, capable of inhabiting more than one role. Her fiction contains multitudes. For example, she’s often described as “middle class,” but I’ll be damned if I don’t see in some of these stories as much of an affinity for Charles Bukowski as Anton Chekhov. In some of the later mystical stories, she also can conjure up an outright religious experimentalism that suggests a whole other set of writers entirely, and when she injects surrealism it’s in a way that reminds me of the artist and writer Leonora Carrington.

And then there are the total outliers among her works, stories that suggest no one but herself. Take Lispector’s almost-folktale “A Chicken,” in which dinner takes flight and must be caught and brought home … after which the chased chicken can no longer be viewed as just food. No influence can explain a writer who can go from the register on display in “A Chicken” to the mind-blowing phantasmagoric stream of consciousness of “Brasília,” a complex, ambivalent reverie about an entire city that is by turns raucous, silly, profane, hilarious, mournful, satirical, and sometimes journalistic. “In Brasília are the craters of the moon,” she writes. “The beauty of Brasília is its invisible statues.” Later, Brasília is “a splattered star”; in the next beat, Lispector writes, “then I’ll say the worst word in the Portuguese language: armpit. And [the authorities will] drop dead.”

I’m hoping “Brasília” was controversial when published in Brazil, but I’m afraid to find out because for me there’s value in experiencing the piece without any warning or context. The story’s breathtaking rhetorical flourishes, its heights and depths, left me gasping in delight and surprise. Especially when, four pages in, Lispector—or her doppelganger—confesses that what you’ve been reading are impressions from Brasília in 1962; everything you read from then on will be more recent impressions. “[Here] is everything I vomited up. Warning: I am about to begin. This piece is accompanied by Strauss’s ‘Vienna Blood’ waltz.”

Sometimes when you don’t care about how many writing rules you break, you wind up somewhere sublime and subversive and original. Reading Lispector, you see this happen with startling regularity. Also with startling regularity, mundane situations in her fiction have incisive or other-dimensional qualities, wedded to a seeming contradiction: She’s awfully good at plunging in and getting to the point, but equally good at digression and adding seeming tangents. These stories change texture and direction at will, but not capriciously.

One story, “The Fifth Story,” is composed entirely of digressions, detailing events that Lispector playfully informs us could be called instead “The Statues,” “The Murder,” or “How to Kill Cockroaches.” In the story, the narrator is “complaining about cockroaches” when “a lady overheard me. The recipe follows. And then comes murder.” This cockroach murder is achieved by mixing flour, sugar, and plaster to create a substance they’ll eat, then die from as the plaster dries inside them. Lispector stacks different versions of cockroach death like a musician performing a dizzying solo. In a scant three pages, she creates an effect similar to what Italo Calvino accomplished in If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, except with a narrative reset button every few paragraphs instead of every chapter. It’s a wondrous trick, if a trick it is—because by story’s end, as in much of this collection, the story has assumed a much greater weight than you imagined encountering its first lines. Lispector slowly pulls back from a small thing—a cockroach in an apartment—to a view of civilization and its “cold, human height.” By the third iteration, the dead cockroaches in dried plaster find their parallel in Pompeii; by the fourth, the cockroaches are entirely sympathetic in their “plaster monuments” as the narrator thinks of them as a vast army under her thrall, deciding between life and death.

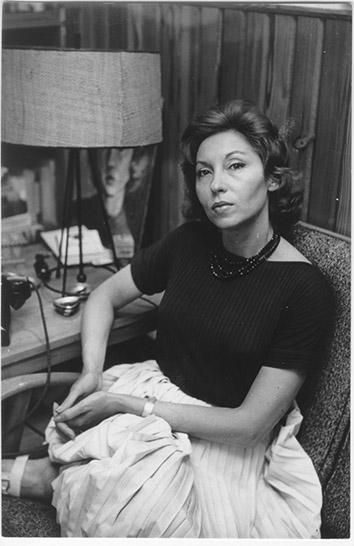

Image courtesy of Benjamin Moser and New Directions

What will “The Fifth Story” be? Lispector, in typical mischievous fashion, leaves that version up to the reader. But this much is true: You will begin by complaining about cockroaches. You will end up somewhere else entirely—somewhere dangerous, unexpected, and infinite.

* * *

The Complete Stories also reveals Lispector’s questing, ever-roving engagement with language, her lifelong task of making words do things other than originally intended. “The cruelty of the world was tranquil. The murder was deep. And death was not what we thought,” Lispector writes in “Love.” These are not common juxtapositions, but sentences that require the reader to splice in what’s left out or to make uncomfortable leaps. They are also the hallmarks of an unusual, creative mind.

Throughout the early stories, this approach to language coexists with a simplicity that only hints at a greater complexity to come. But this quality allows the reader to more easily trace the outlines of themes, to see, for example, that both “Jimmy and I” and “Interrupted Story” are feminist laboratories. In these two stories and others, Lispector confronts the terrible complexity women often face in patriarchies: To truly live, they must think through roles and positions and philosophies of life that are given to men by society involuntarily and unconsciously; they must also withstand being bombarded with the imperative to react to what men say and do.

In “Jimmy and I,” the narrator writes: “I still remember Jimmy, his hair and his ideas. Jimmy thought that nothing is as good as nature.” But the truth conveyed here is that Jimmy doesn’t think “nothing is good as nature”—this is the woman’s analysis of something Jimmy has expressed without ever thinking about it. The narrator has had to intuit it or translate it from the way Jimmy lives his life. When confronted with her analysis, Jimmy recoils; if he can’t be natural then he must perhaps acknowledge that other key parts of his world, the parts he benefits from, are constructs, too.

Image courtesy of Benjamin Moser and New Directions

“He never spoke to me without making it understood that his gravest flaw lay in his tendency toward destruction,” the narrator of “Interrupted” tells us, and here Lispector creates tension from the observation that the myths a man creates about himself are imposed on the world and his relationships—the weight of his “tendency toward destruction” pushed onto others. “Either I destroy him or he’ll destroy me,” she says later in the story, after understanding that the man’s affectations, his self-image, are meant to obliterate her. In both stories, the women narrators behave almost like social scientists, studying men through trial-and-error responses, within the context of their romantic relationships. This inquiry might on a surface level seem to support wanting to understand the other person in a relationship, but underneath the truth is clear: Doing so is an act of survival for both women.

In these stories and in her later, more mature work, the effortless way in which Lispector enters the private lives of her characters creates a sense of intimacy with the reader. But the other key element is the sober focus brought by the acute intelligence of her characters. Even the drunkest or least fortunate of her protagonists are sharp, questing people who have interesting views of the world.

This quality manifests itself, at times, in a sense that the author herself feels trapped by words, frustrated by them. Take, for example, the woman getting drunk by herself in “Daydreams and Drunkenness of a Young Lady.” “Her snow-white flesh was sweet as a lobster’s,” Lispector writes, followed by a destabilizing clang: “the legs of a live lobster wriggling slowly in the air.” And then, Lispector twists once again, refusing to sit still: “And that urge to feel wicked so as to deepen the sweetness into awfulness.”

The way the mind receives sensation and projects thought creates contradiction, anomaly, paradox. This contradiction accounts in part for the juxtaposition of the odd and the “normal” in Lispector’s fiction. I love in particular in “Daydreams” a scene in which once the woman has returned home, “everything became flesh once more, the foot of the bed made of flesh, the window made of flesh, the suit made of flesh her husband had tossed on the chair, and everything nearly aching.”

Finding the absurdity or oddness in reality is, in isolation, a good enough magician’s trick, one that has sustained entire literary careers. But the joy in discovering Lispector is that she fuses the trick to a simultaneous sense of the universal, often in the same sentence or paragraph. Her characters could never be anyone else, yet they are also all of us.

“Oh, words, words,” Lispector writes in that same story—“bedroom objects lined up in word order, forming those murky, bothersome sentences.” I find that’s how I feel trying to explicate Lispector’s fiction—how can I make clear her amazing effects without reproducing an entire story? The first part of editor Benjamin Moser’s introduction, “Glamour and Grammar,” doesn’t help much in that regard. In fact, I suggest you consider it an afterword and treat it accordingly. Moser leads with a bizarre reverie about “glamour and sorcery,” citing Catholic Easter ritual, which clangs with the influence of Jewish mysticism on Lispector. References to shape-shifting and witchcraft and to her appearance position Lispector in an exoticized space and create an unwelcome chimera of her work and her life.

I’m not a big fan of this approach to discussing a novelist’s work. Just as I wouldn’t need to know (or read) that Ian McEwan the person has, say, a luscious but coy handsomeness, I don’t need to know that Lispector’s “glamour is dangerous” and that she inspired “magnetic love,” whatever that is. Certainly, I would have traded magnetic love and a dangerous glamour for an anchor of the usual biographical facts or literary analysis. A more unified and upfront explanation of the book’s contents would have been useful, too. It’s only from the bibliographical note in the book’s end matter that we know that sub-sections like “Family Ties” and “Where Were You at Night” refer to prior story collections published in Brazil. To me, this organizing principle was also unnecessarily confusing, given New Directions hasn’t included publication dates with the stories. The reader interested in charting the progression of Lispector’s talent and preoccupations cannot quite get a grip on the chronology except in the most general way.

Much more useful is the second part of Moser’s introduction, in which he points out how unusual and valuable it is to have a “complete works” from a woman writer that spans her entire life—not broken up due to marriage or raising children. Also useful is the observation that Lispector championed silenced women: “Had any writer ever described a seventy-seven-year-old lady dreaming of coitus with a pop star, or an eighty-one-year-old woman masturbating?” For that matter, I’d add, has anyone as skillfully chronicled the inconsistencies and unfairness of youth, as exemplified by such major stories as “The Disasters of Sofia” or “The Message”?

Reading these stories, I had the same feeling I had when I first read the collected stories of Angela Carter and of Vladimir Nabokov: that something lives beyond the skin and in the skin, and you welcome the invasion, you begin to long for it every time you’re away from the book. You read slow, you read fast, you hold stories back and then devour them, you dread that moment when you’ve finished the last of them. Because the strangeness is familiar and yet different than you’ve ever encountered before. Because life seems more vital, almost hyperreal, after reading Lispector, and it is harder to ignore the hidden life surging all around you, in all its many forms.

All three of those writers suffered from the same affliction of genius: They saw with absolute clarity, and they divined more connections between elements in the world than other writers. Having Carter and Nabokov in my reading life has always been a gift. In introducing me to a third writer of their caliber, The Complete Stories is a discovery every bit as joyous and revelatory.

—

The Complete Stories by Clarice Lispector, translated by Katrina Dodson. Edited by Benjamin Moser. New Directions.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.