When its publisher announced in early 2015 that The Festival of Insignificance, Milan Kundera’s first novel in 13 years, would be a “summation of his life’s work,” fans were giddy with anticipation. With uncanny prescience, Kundera’s previous books all but predicted our Instagram era—what would he have to say about the Panopticon we now live in? Kundera is also the most notorious Russophobe of modern European letters—would he enjoy an I-told-you-so moment, addressing Russia’s recent return to authoritarianism, its invasions of Georgia and Ukraine, and its Soviet-style effort to whitewash its history? And what about his stubborn hatred of pop music—as a citizen of France, would he at least admit that the guitar riff in that Daft Punk song is pretty sweet? Alas, none of the above—no musings on the Internet or rants about the ubiquitous cellphone camera, no mention of Vladimir Putin, and no discussion of music.

And yet this slight but wonderful novel offers its own distinct brand of pleasure. At 115 pages, with the large font for which Kundera has long agitated, Insignificance is his shortest novel and can be read in a single sitting. It focuses on the friendship among four Parisian men: Alain, who is dating a much younger woman we never meet; Ramon, a melancholy retired academic and the oldest of the bunch; Charles, a caterer; and Caliban, an unemployed actor who works as a waiter at Charles’ parties. Rounding out the cast of characters are a Parisian widow named Madame La Franck, a Gogolian nonentity named Quaquelique, and, umm, Joseph Stalin. The centerpiece of the action is a birthday party catered by Charles for their acquaintance D’Ardelo, who has just learned from his doctor that, despite some worrying symptoms, he does not have cancer, but who decides to tell his friends that he does.

Never in a Kundera novel has plot mattered less. Instead, the party merely serves as a platform on which Kundera can examine themes that will be familiar to his readers—for example, the absurdity of history. As citizens of a small nation frequently subjected to the whims of larger neighboring empires, Czech writers often excel at seeing the comedy in historical events, from Jaroslav Hasek’s The Good Soldier Svejk (the urtext of the subgenre) to Josef Skvorecky’s The Cowards to Bohumil Hrabal’s (and Jiri Menzel’s) Closely Watched Trains. In Insignificance, Kundera casts his eye on the fact that the city of Konigsberg, the home of the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant, is now Kaliningrad, named for a Soviet mediocrity with bladder problems.

As was the case in Life is Elsewhere, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and Ignorance, Mommy issues are front and center in Insignificance, as Charles is worried about his ailing mother and Alain is haunted by memories of the woman who abandoned him when he was a 10-year-old boy. Though the novel begins with Alain contemplating the sexualization of the navel, don’t be fooled—what really interests him about our belly buttons is that they’re the sole vestiges of the leashes that once tied us to our mothers. Later, he imagines the entire human race as a towering family tree rising to the sky, connected by umbilical cords.

Another theme that Kundera revisits in Insignificance is the futility of interpersonal communication. Kundera has long portrayed us humans as incompetent communicators; most of his characters are uninterested in others or incapable of truly connecting. In The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, for example, he described the practice of sharing details about oneself as “a brute revolt against brute force, an attempt to free one’s ear from bondage.” And in The Joke, Kundera quotes the Czech poet Frantisek Halas:

Fatuous words I don’t trust you I trust silence

More than beauty more than anything

A festival of understanding

With Insignificance, Kundera playfully takes his skepticism about conversation to an absurd extreme: To liven up his otherwise boring work waiting tables, Caliban pretends to be from Pakistan and only communicates in a Sid Caesar-style gibberish of his own invention. Fatuous words, indeed.

Kundera’s works of fiction can be divided neatly into three categories: the Czech period (The Joke, Laughable Loves, The Farewell Waltz, Life Is Elsewhere), when he lived in Czechoslovakia and wrote primarily for that domestic audience; the Czech-in-exile period (The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Immortality), when he had emigrated to France but continued to write in Czech; and finally, his French-language period (Slowness, Identity, Ignorance, and now, The Festival of Insignificance). The transition to each new period saw changes to his prose style. After he left Communist Czechoslovakia, Kundera found himself in an extraordinary predicament for a writer—except for a tiny minority, all of his readers would be reading him in translation. From that point forward, he constructed every sentence so as to minimize the risk that a translator could screw it up. As he explained in The Art of the Novel, “For me, because practically speaking I no longer have the Czech audience, translations are everything.” (The Festival of Insignificance, like all his French-language novels, was translated by Linda Asher.)

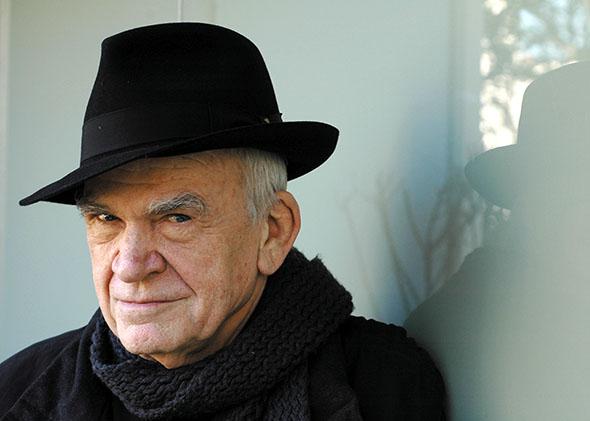

So while Kundera never aspired to Dickensian baroqueness, his prose in the middle period became leaner, almost spare. These novels sometimes resemble Supreme Court opinions, with numbered chapters and plain language carefully guiding the reader toward the author’s position. And with the switch to French, Kundera’s style grew sparser still. He largely eliminated the essayistic sections that characterized his earlier work. I have two theories about why. One is that he had seen the artistic benefits that minimalism brings and wanted to carry them even further. The other is simply that, as an elderly man (born in 1929, Kundera was almost certainly in his 80s when he wrote Insignificance), he knew that time was limited and that he therefore didn’t have the luxury of embarking on projects as ambitious as those of his middle period.

Insignificance benefits from such narrative restraint. In his earlier fiction, Kundera, like a bird that chews food for her babies, had a habit of over-explaining the text, as if compelled by his pessimism about human communication. True, this clarity lent his middle-period novels a force that most writers would envy. But his worldview often felt binary and reductive; with his overpowering certitude Kundera could come across like the Justice Scalia of European literature. In Insignificance, though, he loosens his narrative grip and lets the text speak for itself.

And what a delightful text it is. For a writer so interested in laughter (his early titles include The Joke, Laughable Loves, and The Book of Laughter and Forgetting), Kundera has seldom provided much of it; he often comes across as the misanthrope scowling in the corner at the party, criticizing the idiocy of the other guests. His characters have at times felt like caricatures created solely to illustrate a personality trait that the author finds noxious. And in his recent work he’s shown symptoms of Grumpy Old Man Syndrome, railing against the ugliness of modern life, with its crowds and its traffic and its loud music.

But here Kundera’s affection for the four main characters (“heroes,” he calls them) lends the novel a sanguine mood. Instead of rants about modernity, we get sincere, witty conversations among friends who are earnestly trying to help each other find happiness in this “Festival of Insignificance” called life. At one point during D’Ardelo’s party, Ramon captures the spirit of the novel: “We’ve known for a long time that it was no longer possible to overturn this world, nor reshape it, nor head off its dangerous headlong rush. There’s been only one possible resistance: to not take it seriously.”

Kundera has always celebrated the liberation that comes with old age. He once speculated that Goethe felt “a sense of inexpressible joy and a sudden surge of vitality” during his last days, released from considerations about his legacy. In his criticism, he has singled out for praise the work that Beethoven, Janacek, and Fellini created toward the end of their lives.

With this magic trick of a novel, it’s clear that Kundera, now 86, is living the geriatric dream. Insignificance is the work not of a grumpy old man but of a grinning old man. Kundera still believes that life is a trap—as Alain’s mother puts it, “Of all the people you see, no one is here by his own wish”—but, as if intoxicated by the nearness of his release from that trap, his reaction to that core existential truth has bloomed from despair into laughter. With its mix of reality and fantasy, comedy and melancholy, Insignificance calls to mind the Fellini films Kundera so reveres. In the novel’s surreal, pitch-perfect final scene, you can practically hear the Nino Rota music playing in the background.

In a chapter of Testaments Betrayed called “Delight and Ecstasy,” Kundera writes:

I remember the Picasso exhibition in Prague in the mid-sixties. One painting has stayed with me. A woman and a man are eating watermelon: the woman is seated, the man is lying on the ground, his legs lifted up to the sky in a gesture of unspeakable joy. And the whole thing painted with a delectable offhandedness that made me think the painter, as he painted the picture, must have been feeling the same joy as the man with his legs lifted up.

One can’t help but think that this description of Picasso, filled with joy as he painted, perfectly describes Kundera’s state of mind as he wrote Insignificance. If this is the last novel he ever publishes, it will make for a fitting capstone on an extraordinary career.

—

The Festival of Insignificance by Milan Kundera. Harper Collins.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.