Invitingly small, little more than pocket-size—the pocket in some cargo pants, perhaps—Colm Tóibín’s On Elizabeth Bishop is, at different moments and to varying degrees, a primer and a personal reflection; an introduction to Bishop and a consideration of a poet, Thom Gunn, who neither influenced nor was influenced by her; thoroughly beautiful and slightly pedantic; careful to see the poems in all their complexity and too willing to boil their virtues down to a single effect; an easy read informed by voluminous reading; too little and too much. I enjoyed most of its 199 narrow pages and was awed by many, yet I would be wary of recommending it to someone because I can’t say with any consistency whom (or what) it’s for.

The book opens masterfully, in a kind of critical medias res:

She began with the idea that little is known and that much is puzzling. The effort, then, to make a true statement in poetry—to claim that something is something, or does something—required a hushed, solitary concentration. A true statement for her carried with it, buried in its rhythm, considerable degrees of irony because it was oddly futile; it was either too simple or too loaded to mean a great deal. It did not do anything much, other than distract or briefly please the reader. Nonetheless, it was essential for Elizabeth Bishop that the words in a statement be precise and exact. “Since we do float on an unknown sea,” she wrote to Robert Lowell, “I think we should examine the other floating things that come our way carefully; who knows what might depend on it?”

Amazingly, Tóibín persists in that mode for an entire chapter. It’s prose as a model of the particular way in which poems can matter—personal even in abstraction, lived-in, enlarged through a lifetime of intermittent attention and honed by the persistent challenge to say what this thing is and why it feels so important. The insights and observations are so thoroughly distilled, so precisely named, that they should feel viscous and thick, yet the prose has an unhurried grace in which the feeling of discovery persists. (In this, it sounds a lot like Bishop.) It’s an image of the way that certain poems seem to live with us—expanding and altering somewhere in the imperfect, recursive maps of memory.

The second chapter, like the first, begins with a sentence that seems to continue a thought that started offstage: “The sense that we are only ourselves and that other people feel the same way—that they too are only themselves—is a curious thought.”

But shortly after that, Tóibín becomes a different writer, one who assumes his reader hasn’t encountered Bishop’s most famous poems and who walks through them slowly, didactically, alternating between excerpts and capsule summaries. Following the first five lines of “In the Waiting Room,” he explains:

The child, as she reads the National Geographic magazine, is horrified by the photographs of naked black women until she is distracted by the sound of her aunt in the dentist’s chair crying out. For a second she begins to believe that the cry is coming not from the aunt but actually from her (“Without thinking at all / I was my foolish aunt”). Then slowly it occurs to her that she is not her aunt, but herself.

How disappointing to encounter so much of an extraordinary poem as nothing but plot points. The summary omits, for example, Bishop’s terrifyingly plain descriptions of those pictures:

black, naked women with necks

wound round and round with wire

like the necks of light bulbs.

Their breasts were horrifying.

Lost is the terrible ease with which the photograph turns bodies into curiosities—and the feeling of just how otherworldly a woman’s body could look in that room “full of grown-up people,/ arctics and overcoats.” Lost, too, is the tone of that last sentence (“Their breasts were horrifying”): sickeningly flat, small, and contained, a self-judgment-in-waiting. The line sounds eerily like the sentence that tries to contain queerness in another great poem from Bishop’s final book, “Crusoe in England”: “Pretty to watch; he had a pretty body.”

Tóibín’s gloss mutes the way the poem resurrects, in glimmers that go out fast, some aspect of the child-Bishop inside the still-careful voice of the adult. It mutes the quiet, confident rhythm that only just masters the memory of those feelings—and the feelings themselves, which were, along with the attempt to manage them, the beginnings of the poet who would one day write:

I wasn’t at all surprised;

even then I knew she was

a foolish, timid woman.

I might have been embarrassed,

but wasn’t. What took me

completely by surprise

was that it was me:

my voice, in my mouth.

I don’t mean to suggest that Tóibín needed to say these things or share these lines. He had other points to make, and he makes most of them beautifully. I just wish he’d skipped the thousands of lines those pedestrian summaries skim across. In his recaps, Tóibín can make poems into strangely impersonal objects, a series of paraphrasable events and meanings to be understood and carried off, rather than a complex of physical, intellectual, and even interpersonal experiences one might have and re-have in ways that shift as richly as memory.

Elsewhere, though, and often, Tóibín nails it. He demonstrates the possibility of coming to life in someone else’s poem, in the long labor of sorting through and returning to it like any important event in one’s life. (Here, too, he reminds me of Bishop.) He writes about his first favorite among Bishop’s poems, “Cirque d’Hiver,” a choice he finds peculiar now:

The poem seems so determined to be jolly and inconsequential, almost jokey, that it is hard to find the undertow in it, which arises oddly from the sheer amount of time and energy spent observing this scene in such great and good-humored detail to the exclusion of all else. Somehow, I felt a sense that, in concentrating on this and this only for a long time, the poem hinted that the rest of the world could be kept away and made to seem not to matter.

That explanation, with its welcome, implicit admission that poems, like people, can be useful, and that using a poem can be both awkward and profound, comes in the midst of a brief autobiography of Tóibín’s early years with Bishop’s poems. Tóibín overlaps his life with Bishop’s—both of them gay, both from places where “language was also a way to restrain experience,” both having lost parents at a young age and in the midst of heavy and enduring silence. It’s a risky move, but it works out beautifully, presenting a rare image of the similarities between reading and writing, how both happen not just in the midst of a given life but as a part of it.

It works out, too, as does so much else in this book, because Tóibín has a seemingly effortless ability to find illuminating patterns or summon the right quotation at the right moment. He pulls with similar ease and aptness from Bishop, her friends, and critics, even from the separate but similar landscapes he (a native of Ireland) and Bishop (whose first and last true home was in Nova Scotia) share. Take his reflection on “At the Fishhouses,” which comes near the end of a long, unlikely, gorgeous parallel tracing of Bishop and Joyce:

Ireland and Nova Scotia have their inhospitable seasons and their barren hinterlands; they are places where the light is often scarce and the memory of poverty is close; they are places in which the spirit and the past comes haunting and much is unresolved.

At a few points, wandering down one of those paths, Tóibín lets idiosyncrasy carry him too far, and he loses track of Bishop. He devotes at least 10 percent of On Elizabeth Bishop to Thom Gunn. Gunn was an extraordinary poet in his own right, and he occasionally proves useful in highlighting some aspect of Bishop’s poetry, but the two had neither a personal nor a literary connection of any note, and the overlaps in their poems seem largely incidental.

But I’ve already spent too much time on the book’s shortcomings (especially since I still have one bone left to pick). I’ve done so, I think, because while the book’s occasional flaws vary so greatly, its chief virtues remain unwaveringly the same: it’s smart, it’s accurate, it’s warm, and it’s exquisite. Sentence after sentence, Tóibín is simply wonderful to read. Here he is back in that breathtaking first chapter:

This enacting of a search for further precision and further care with terms was, in one way, a trick, a way of making the reader believe and trust a voice, or a way of quietly asking the reader to follow the poem’s casual and then deliberate efforts to be faithful to what it saw, or what it knew. The trick established limits, exalted precision, made the bringing of things down to themselves into a sort of conspiracy with the reader.

But somewhere in there, too, is the seed of my one real disagreement with On Elizabeth Bishop. The clumsy summaries and the strange digressions are easily outweighed by the pleasures of so much writing on Bishop that reads so well and runs so deep. But as the book goes on, Tóibín begins pointing all his varied insights into the poems toward a single virtue. “Not having that confidence gave Bishop her power.” “The scream was all the more powerful because it was almost, not quite, shrugged off as nothing.” “The music or the power was in what was often left out. The smallest word, or holding of breath, could have a fierce, stony power.” “[T]he language of transcendence can have a special power.” “[T]he devious power of these late poems.” “[T]ake some of their power.” And so it goes.

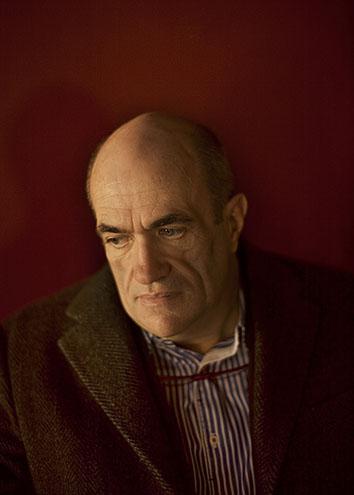

Photo by Phoebe Ling

Tóibín’s not wrong. Bishop’s poems are powerful. It’s just that power, as a catchall term for poetic success, tends to focus our attention in the wrong places. In the case of Bishop, this focus risks trivializing (“a trick”) her willingness to abdicate some kinds of literary power—power she held in abundance—in service of honesty.

Consider the letter, quoted by Tóibín, that Bishop wrote to Robert Lowell after he sent her a draft of The Dolphin. Bishop was appalled that Lowell had included and altered numerous letters from Elizabeth Hardwick, the wife he had abandoned and left to raise their daughter alone. She first complimented the poems, noting, “they affect me immediately and profoundly.” But such power, for Bishop, wasn’t the point—or, at least, it wasn’t point enough. She continued, scolding him, “art just isn’t worth that much.”

How many other poets of real and lasting merit could have written that?

Far more than a response to the anti-gay bigotry of her time (though it was that, too), Bishop’s modesty was an intellectual and moral position. It took root in the values of the world in which she felt briefly at home as a child, before never feeling at home again. This was the fading world of the taciturn fisherman, the blade of his knife “almost worn away”—a world in which one person shouldn’t pretend to matter more than anyone else. Tóibín quotes another letter to Lowell. In it, Bishop jokes, self-effacingly, about her “George-Washington-handicap”: “I can’t tell a lie even for art, apparently; it takes an awful lot of effort or a sudden jolt to make me alter the facts.”

Many of Bishop’s best poems are self-portraits of the artist trying to see beyond herself. They seem driven by a need to take an object or event of intense and sometimes baffling personal significance to the speaker (“as when emotion too far exceeds its cause”) and justify its importance. They are full of repetitions and subtle corrections, the speaker resisting the temptation to reach for universal terms. (“Our visions coincided—‘visions’ is/ too serious a word—our looks, two looks.”) The entire drama of “The Fish” involves Bishop pulling “a tremendous fish” close enough, metaphorically, to see it clearly, then once again pushing it away to avoid turning it into a metaphor. Art mattered immensely to Bishop, but only because it was beholden to something else.

Power is best understood as the power to: to comfort, instruct, silence, exalt, etc. Toward the end of “The Moose,” which Bishop famously worked on for 20 years, she is describing some older passengers talking in the back of the bus as others fall asleep, “Talking the way they talked/ in the old featherbed,/ peacefully, on and on.” She imagines it as a heaven of talk, “Grandparents’ voices/ uninterruptedly/ talking, in Eternity,” though the news (most of it no longer news) they share is all bad. She picks up the word “Yes,” which had popped up in another passenger’s almost meaningless statement earlier:

He took to drink. Yes.

She went to the bad.

When Amos began to pray

even in the store and

finally the family had

to put him away.

“Yes…” that peculiar

affirmative. “Yes…”

A sharp, indrawn breath,

half groan, half acceptance,

that means “Life’s like that.

We know it (also death).”

“That peculiar/ affirmative.” For all of Bishop’s reluctance to generalize, she is often, within her poems, an acute interpreter of her own work. (She is also, like most of us, frequently paradoxical, which is part of what makes her portrait of modesty so accurate: It knows the appeal of grandeur, too. When, after circling, then speeding up, then refusing to lift off multiple times in “At the Fishhouses,” she finally unleashes the impulse, the result is some of the most rapturous writing imaginable—though it would be unimaginable if she hadn’t written it.) So often, for me, “that peculiar affirmative” is what Bishop presents more richly and consolingly than anyone else.

The long, careful work of these words, the carefully rendered hesitations, the statements written in order to be written out, the amount of time it took for Bishop to craft the impression of producing a single, continuous strand of consciousness: These poems are the result of exactly what they enact—an attempt to get it right. They are, that is to say, Bishop herself. And they are, peculiarly, affirmative—the self-present, the self-absolved, the disappointments of life scaled down into something that feels vast, but also manageable. The world is often too large, too lonely, too often “only connected by ‘and’ and ‘and,’ ” but also, up to a point, comprehensible, observable, something that, if we are careful enough, we can share.

“Why,” asks Bishop near the end of “The Moose,” “why do we feel/ (we all feel) this sweet/ sensation of joy?” And then, “ ‘Curious creatures,’/ says our quiet driver,/ rolling his r’s.” His response is deliciously insufficient—and therefore exactly right, as is the way the word curious expands in the mind. It means us, too, equally foreign and strange, and the way the “we” that “all feel” also want to feel, to see those other floating things. On Elizabeth Bishop is a curious book. And if I’m not sure what to make of it at times, I’m grateful to have met Tóibín over these poems, to have felt, in the presence of such beauty—both Bishop’s and his—some of what he has felt.

—

On Elizabeth Bishop by Colm Tóibín. Princeton.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.