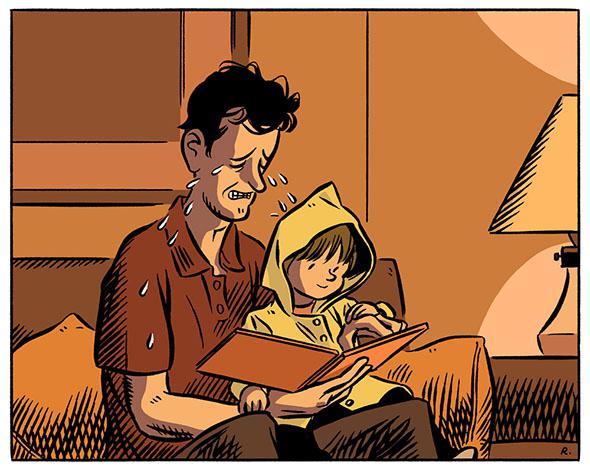

I can’t remember the last time I cried at a grown-up novel or film, but certain children’s books and movies make me cry every time. I know many parents who share my weakness: There you are, sitting on the couch with a kid, pleasantly killing half an hour with a stack of picture books, when a story strikes a particular chord of sentimentality and all of a sudden tears are streaming down your face and you’re fighting to keep your voice steady.

Pixar’s Inside Out appeared in theaters in June and immediately entered the canon of children’s stories known to induce parental weeping. There are touching moments for the softhearted throughout the movie but the money shot, lacrimationally speaking, comes at the end of the second act. (If you haven’t seen Inside Out, here comes a spoiler. If you have, you’re probably starting to tear up a bit and should feel free to skip the rest of this paragraph.) The film is set inside the mind of Riley, an unhappy 11-year-old girl. The moment when theaters across the country are wracked with adult sobs comes when Riley’s early-childhood imaginary friend, Bing Bong, consigns himself to the Memory Dump—a lightless abyss where experiences are left to fade into oblivion. It’s the familiar heroic-sacrifice trope from war movies and adventure stories, with the death scene played by a pink elephant-cat-dolphin hybrid. It left me gasping for air.

The demise of the imaginary friend is a tried-and-true way to turn a whimsical children’s story into a tearjerker. Look, for instance, at the end of The House at Pooh Corner, the sequel to A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh, in which Christopher Robin, leaving for boarding school, says goodbye to his ursine pal. Being English, he can’t quite say what he means, but to an adult reader the message is clear: He won’t have much time to play with his toy animals any more and, worse, soon he won’t want to play with them. And so the kind, flawed, funny characters with whom we’ve just spent two books are cast aside forever.

A children’s story can’t end on a note of complete tragedy—we don’t tell children quite how terrible the world is all at once. So Inside Out gets Bing Bong’s sacrifice out of the way, then lets the movie proceed to its (entirely earned and satisfying) happy ending. He does Riley one last service, and then he fades away—the role of an imaginary friend in a healthy childhood, snapping exactly into the structure of a Hollywood adventure screenplay. Whereas Milne has to sweeten his conclusion with a white lie about how, “in that enchanted place on the top of the Forest, a little boy and his Bear will always be playing.” In fact, the little boy and his bear are no longer playing. The bear is still there at the top of the forest, alone, waiting for the boy to come back. But the boy is gone.

For children, focused on what they’re becoming, growing up is not a tragedy. Which is why it’s us, the adults, who are crying, with a mixture of grief and guilt, for all the things we’ve abandoned.

* * *

I don’t mind crying, and I’m certainly not the kind of old-school dad who thinks displays of emotion are dishonorable, but I’m still not entirely comfortable crying in front of my children. One of the pleasant things about little kids is that it’s easy to look grown-up and powerful to them. I like to think that they perceive me as moving through the world with casual mastery, changing light bulbs and making sandwiches and explaining how television works. I don’t necessarily want them to see me being unmanned by The House at Pooh Corner.

But young children haven’t been socialized to respond to other people’s distress, and their responses to unusual stimuli such as their parents crying are unpredictable. Mine sometimes wait patiently for me to get back to the story; more often they just order me to keep going. So much of the world is a mystery to them anyway—what’s one inexplicable bout of paternal weeping?

Like the Pooh books, Mo Willems’ popular Knuffle Bunny trilogy is about a child’s intense love for a favorite toy, but here it’s presented from a wry distance. In each volume of the series Trixie loses her bunny and then finds him, but the books never extend subjectivity to Knuffle Bunny himself, as Trixie presumably does. Finally, in Knuffle Bunny Free, she’s old enough to give him away, a maturity she arrives at with minimal heartbreak. It’s all very sweet, enlivened by Willems’ usual deft jokes and skillful cartooning, and I can enjoy it without being especially moved—right up until the epilogue, in which Trixie grows up, gets married, starts a family, and is reunited with her old toy. The epilogue is three pages long, and it collapses the next 25 years of my life into an instant, and every time it makes me cry my eyes out.

Julia Donaldson’s beautiful The Paper Dolls has a similar ending: The loss of the beloved paper dolls is mitigated by the passage of time, which allows the child heroine to grow into a mother and make paper dolls for her own daughter. That one makes me cry too. And so, to my profound shame, does Love You Forever, an unpleasant Canadian blockbuster in which a mother sings a clumsy lullaby to her growing son every night until the grown son sings it to the dying mother and to his own infant child. I’m sure my personal vulnerabilities are in play here, but other parents report similar bouts of weeping at these moments, in which time is accelerated to depict a child character growing into adulthood and parenthood.

Parenting does strange things to your perception of time. The routine tasks that keep children alive and healthy make the hours drag on endlessly, but beneath that tedium is a constant awareness of time’s inexorable passage. You miss the infant or toddler you had a year ago; you anticipate missing the child who’s there with you now, urinating on the couch or asking, for the fifth time that morning, when she can have a dress like the one Elsa wears in Frozen but a long one, not like the short one she already has, and also a crown to go with it. So the experience of parenthood consists of a never-ending series of small annoyances layered on top of a briskly unfolding tragedy.

Whereas children exist in their own endless present; everything takes forever to them. Reading to a child, falling into the rhythm of the words and the pages, is as close as I can reliably get to joining my daughter in her slowed-down kid time. That’s what makes it so painful to turn the final pages of these books and watch a child grow up all at once. Adult time rushes back in to disrupt your slow-motion reverie. The little girl leaning her head against your chest will soon be able to read for herself. And then, before you know it, she’ll have no more need for you, and she’ll think about you sometimes, guiltily, but your purpose will have been served. She’ll be fine. But, like an imaginary friend, you’ll be gone.