Armada is a story about how gamers are the most important people in the world. This is not a new story; it’s served as the inspiration for countless video games over the past 40 years, not to mention the recent harassment campaigns that spawned out of gaming culture and the wounded, entitled pride at their heart. While the aims of the novel are onanistic rather than malicious, Armada nonetheless demands to be bronzed as the perfect embodiment of the impulses that so often make games—and gaming culture—boring, self-indulgent, and regressive.

Armada is the highly anticipated second novel from Ernest Cline, who hit the best-seller list in 2011 with his debut, Ready Player One. Set in 2044, that first sci-fi adventure took place in a dystopian future in which people escape their lives by jacking into a virtual reality universe. This VR world was created by a programmer who was obsessed with ’80s geek culture and built an elaborate treasure hunt into the game based on his very specific predilections. The resulting journey was a confectionary pastiche where the player who essentially “got” the most ’80s references was promised vast, godlike abilities, and the worship of nostalgia was framed as the path to happiness, salvation, and power.

Although this sounds like fertile ground for a critique of the inward-facing tendencies that so often pervade modern gaming, Ready Player One was far too joyously self-absorbed in its referential excesses to step back and examine what they might mean. It was still a page-turner, though. Armada is neither as immersive nor as fun, though it remains just as committed to sucking the sweet, nostalgic marrow from superior works of science fiction and pop culture.

This time around, our hero is Zack Lightman, a high school student who is one of the best players in the world at the fictional space shooting game Armada. After nearly 100 pages of overly specific descriptions of Zack’s online battles with his friends, everything changes when a spaceship ripped from the game itself lands on the front lawn of school, and a man emerges to announce that Zack is so good at video games that he has been enlisted to fight aliens.

If that sounds familiar to you, that’s probably because you’ve seen the movie The Last Starfighter, which is about a young boy who is so good at video games that he is enlisted to fight aliens. Or perhaps Ender’s Game, a story about a young boy who is so good at video games that he is enlisted to fight aliens. In an interview with the Verge, Cline explained the secret sauce that makes his story different from the other sci-fi tales that have told similar stories: Yup, it’s pop culture references. “In a zombie apocalypse movie,” he said, “nobody’s ever seen a zombie movie. Or in an alien invasion movie, nobody has ever seen an alien invasion movie like Independence Day. That’s what Armada is — if an alien invasion happened today, we’d be aware of all of that and reference all of this pop culture.”

Indeed, after Zack blasts off to join the Earth Defense Alliance, he explains how he feels again and again not by telling us, but by referencing the experiences of main characters from better versions of this story: “I felt like Luke Skywalker surveying a hangar full of A-, Y- and X-Wing Fighters just before the Battle of Yavin. Or Captain Apollo, climbing into the cockpit of his Viper on the Galactica’s flight deck. Ender Wiggin arriving at Battle School. Or Alex Rogan, clutching his Star League uniform, staring wide-eyed at a hangar full of Gunstars.”

Barely a page goes by without a reference to Star Wars, Dungeons & Dragons, Flight of the Navigator, Transformers, Starfox, Space Invaders, Zero Wing, Iron Eagle, Star Trek, and on and on and on. Geek culture has long been preoccupied with trivia; the ability to recognize and make references to games, movies, and TV shows beloved within various “geeky” subcultures is often considered an in-group badge of honor, a signifier of credibility and even power. Armada is a book designed entirely around getting the reference—high-fiving the readers who recognize its shoutouts while leaving everyone else trapped behind a nerd-culture velvet rope of catchphrases and codes.

Armada often feels like it’s being narrated by that one guy in your group of friends who never stops quoting the Simpsons, a tic that feels increasingly tiresome and off-putting in the face of the novel’s supposedly apocalyptic stakes. On more than one occasion, soldiers salute each other en route to world-ending battles by solemnly swearing that “the Force” will be with them, and one character flies to his supposedly tragic and moving death while screaming quotes from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. This is a book that ends with someone unironically quoting Yoda.

The shameless, jejune wish-fulfillment of the book burns hot and bright, from the moment our young gamer hero gets summoned to space from the lawn of his school, while the girl who dumped him and the jerk who bullied him look on with disbelief. When players like Zack are recruited into the Earth Defense Alliance, their in-game prestige also immediately translates into military rank and real-life power. “Elite” recruits like Zack are immediately promoted to flight officer, meaning they immediately outrank many of the enlisted men, even if the flight officer is a smart-ass teenager who goes by the handle Kushmaster5000.

We’re also told the government has been tracking the habits of its elite players, and when they arrive at their virtual battle stations, they find their favorite snacks waiting for them, their favorite songs queued up to accompany their virtual space fights, not to mention a “special strain of weed that helps people focus and enhances their ability to play videogames” that’s been cultivated just for them. In one revealing moment, Zack calls his mom in midst of the alien invasion and says the words that burn in the heart of every gamer who has ever felt demeaned for the hours they lavish on their favorite hobby: “All those years I spent playing videogames weren’t wasted after all, eh?”

Zack’s mom is one of the very few women in the book who get any airtime at all, as is his love interest, a fellow gamer recruit named Lex. You might wonder: What is Lex about? What motivates her? It doesn’t matter. What’s important about her is that she’s a hot girl from Austin who gets his jokes, has “alabaster skin,” sports a seminude Tank Girl tattoo, and wants to make out with our hero after hearing that he’s one of the best Armada players in the world:

“My Terra Firma ranking is too abysmal to say out loud,” I said, laying on the false modesty with a trowel. “But in the Armada rankings I’m currently sixth.”

Her eyes widened, and she swiveled her head around to stare at me.

“Sixth place?” she repeated. “In the world? No bullshit?”

I crossed my heart, but did not hope to die.

“That’s some serious bill-paying skillage,” she said. “Color me impressed, Zack-Zack Lightman.”

“Color me flattered, Miss Larkin,” I replied.

It’s a cringingly terrible and transparent bit of self-indulgence, one of many in the book that walks so close to the line of video game fan fiction that it becomes nearly indistinguishable.

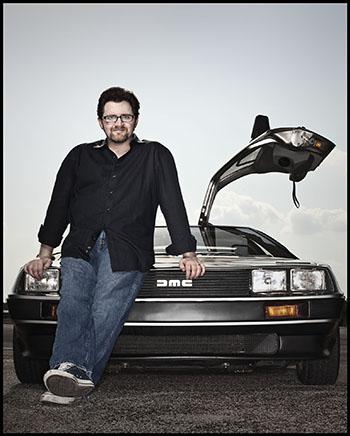

Photo by Dan Winters

Early in the book, Zack rifles through the belongings of his dead father, who died in a mysterious accident but left behind journals that detailed a strange, conspiratorial obsession with ’80s video games and movies. Zack has spent a lot of his life consuming those same games and movies in hopes of recapturing something that has been lost—the same impulse that drives so many people to obsess about the past. But in a brief and fleeting moment of insight, Zack finally decides to close up the boxes and move on with his life. It was “high time [he] grew up,” he decides, adding that “the time had come for me to stop living in the past.”

The novel spends the next 300 pages doing the opposite.

Armada reads like a coming-of-age fantasy for people who came of age long ago; despite the fact that Zack Lightman is only 18 years old, he drives a 1989 Dodge Omni, watches ’80s movies like Say Anything, and can’t stop listening to ZZ Top. We’re told that he’s just immersing himself in the beloved media of his dead father, but hearing a modern-day teenage character talk about ’80s culture with the intimacy and nostalgia of his 43-year-old creator feels more than a little contrived.

And familiar: Ready Player One, the novel that launched Cline’s career, was a sci-fi adventure about teenagers cavorting through a futuristic virtual reality world where the limitless creative possibilities of the digital universe were oddly laser-focused on 1980s pop culture references. The sins of Cline’s era-specific obsessions and wafer-thin characters were forgivable, given the effervescent pleasures of his geek-culture mashup. With Armada, Cline finally has the opportunity to address the question of whether his work has legs beyond the crutch of his referential obsessions. The answer is no.

Our fantasies can tell us a great deal about ourselves, and the fact that Cline’s work has often been trumpeted as the ultimate “nerdgasm” or some sort of apotheosis of nerd culture should be troubling to anyone who identifies with the label. There’s nothing wrong with nostalgia, on its own; our love for the media of our youth—and more importantly, for the qualities that made us love it in the first place—is not only worth remembering, but also capable of sparking new and wonderful creations, so long as we are able to distinguish inspiration from imitation.

It’s a valuable question for gaming culture—and “nerd culture” more generally—to ask itself: Do we want to tell stories that make sense of the things we used to love, that help us remember the reasons we were so drawn to them, and create new works that inspire that level of devotion? Or do we simply want to hear the litany of our childhood repeated back to us like an endless lullaby for the rest of our lives?

Armada is for everyone who wants the latter, a book-length love letter of cultural hyperlinks that refer you elsewhere but contain no meaningful content themselves. Take away the shoutouts and the plot points borrowed wholesale from far better works of science fiction, and the story in Armada doesn’t just fall apart—it doesn’t exist at all. It’s simply a long series of secret handshakes, designed to grant access to the most enduring and beloved fantasy world of so many aging gamers: the idea that nothing will ever be more important than the things they loved when they were young.

—

Armada by Ernest Cline. Crown.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.