On Nov. 21, 2014, the United States launched what Micah Zenko, writing in the Atlantic, termed “its 500th non-battlefield targeted killing.” Exactly two weeks after that strike, which, according to an unnamed source, used two missiles to destroy a house in northwest Pakistan, near the Afghanistan border, killing six people and wounding three more, the American poet Claudia Emerson died from cancer that had traveled from her colon to her liver and brain.

The two events feel painfully unrelated, each seeming to mark the other as out of place and improperly scaled. But such resistance is also a relationship, based in the ways we imagine the different lives death claims. To consider Emerson’s new book of poems, The Opposite House (the first of several that Louisiana State University Press will publish posthumously), in concert with Philip Metres’ Sand Opera (which focuses primarily on victims of the so-called War on Terror, a war whose stated enemy is our feeling of vulnerability itself) is to feel something of the human entanglement we too often refuse to see. Our very sense that these stories have nothing to say to each other should be enough to remind us that the prospect of our own suffering can obscure our ability to see the suffering of others—even inviting us to inflict suffering on others in order to feel less afraid.

Emerson presumably wrote the poems in The Opposite House years before she died, but it’s impossible to keep the news from them. Her gaze narrows and intensifies to an extent that I can’t help assuming—as she tells story after story of old age, demise, time folding so that what is most distant in a life comes nearest to it—that she was working on the far side of a diagnosis of cancer, if not a prognosis of death.

The book’s first poem, “Ephemeris,” is about a woman whose children have brought her home to emptied rooms because, after the belongings sell at auction, “they cannot let the house itself go for / the near-nothing it brings …” Here and throughout, Emerson makes urgency out of patience—slowing the pace of each sentence as if there’s no time to waste on getting this wrong:

Almost emptied,

there is little evidence that she ever

lived in it: a rented hospital bed

in the kitchen where the breakfast table

stood, a borrowed coffee pot, chair,

a cot for the daughter she knows, and then does not.

But the world seems almost right, the near-

familiar curtainless windows, the room

neat, shadow-severed, her body’s thinness,

like her gown’s, a comfort now. Perhaps

she thinks it death and the place a lesser

heaven, the hereafter a bed, the night

to herself, rain percussive in the gutters—

enough.

There’s something bounteous, almost religious, in the graceful turning and opening of these lines, the way Emerson’s concentration grows spacious. “Ephemeris,” which ends with the woman’s diminished mind resurrecting a child who “never suckled / and was buried without a name,” restores both child and mother in the fullness of illusion:

This middle-born

is now the nearer, no, the only child.

The undertaker’s wife has not bathed

and dressed him; the first day’s night instead

has passed, quickening into another

day, and another, and he is again awake,

his fist gripping a spindle of turned light,

and he is ravenous in his cradle of air.

For all that these poems focus on the nearness of death and the persistence of erasure, they seem uninterested in the poet who may have been fearing her own effacement. They relish instead the opportunity to fill a mind with a world that death will one day wipe from that mind (a prospect the mind can also contain for a while). Each new “he” or “she,” even as it draws Emerson back to the ways that these people will eventually lose their sense of self, reiterates the mind that conjures it.

At times, Emerson leans too heavily on coincidence to tie everything together. Having convincingly recorded a speaker’s attempt to respond to the poem’s materials, she can conclude with those materials abruptly and decisively responding to the poet’s will: “the garden a seed / catalog, open on the kitchen table, that / one light she left on downstairs fixed on it.”

With that one light landing so perfectly, Emerson brushes up against the limitations of her intricate, concentrated style. The lines feel falsely parochial, too beguiled by neatness, too happy to see the illusion of self-sufficiency as the achievement of a life.

But the richness of The Opposite House writ large argues for something far more open and complex. The poem “Limb Factory” opens

Despite

the seeming

singularity of the fetal

sonogram—

and then descends through the first long sentence, whose vitality stands as a third image of creation, alongside the bodies crafted by genes and the body parts manufactured in machines:

the industry of it

a study

in loss,

and the argument

against it,

the physics

and engineering

of what

moves, recovers,

resists, and follows

the body’s

original order,

the flux and give

of a gathering

of dust

reproduced piecemeal.

The poem succeeds without satisfying, a made thing that ends, disappointed, with something made:

perhaps such

survival has always been

part conjure,

part clinical,

the muscle twitch

of quickening

a fashioned thing,

interchangeable—

abject this remembrance

not begotten—

made.

We want something more than survival, the poem suggests, even as it admits that survival is an achievement too easily undone. The poem, proceeding jaggedly down the page, announces that it, too, is fashioned, and so the abjection of its ending is doubled but also tempered, brought into an awkward kinship with the lines’ beautiful, staggered range.

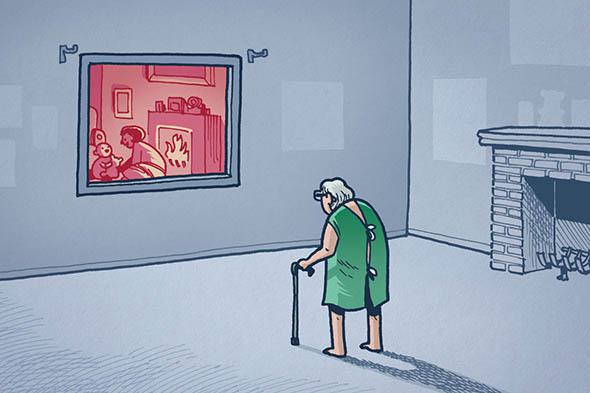

Photo by Robert Muller

Metres’ Sand Opera seems, at first glance, to have nothing in common with The Opposite House. Where Emerson’s best poems concentrate, Metres’ disperse. Where Emerson mostly sees America in the enclosures of its small towns, Metres sees it in its terrifying claim and reach. Where death approaches Emerson’s characters quietly, through slow erosions of consciousness, Metres’ torture victims are forced into constant and excruciating awareness of their vulnerability. And where Emerson tends to look at one life at a time, Metres often works to overlap multiple voices.

But much as fear, post-9/11, sifted into even the most isolated corners of America, and much as we created a mirror image of our fears in our devastating response, the two books concur. In their reverent attention, Metres and Emerson turn care into a structural element, dignifying subjects they can’t protect from harm.

Metres does this best when he’s farthest from the traditional modes in which Emerson excels. In his domestic poem of distant destruction, “Woman Mourning Son,” he writes:

I flip open the news and she flutters out,

trailing the blot of her shadow. I yawn,

her mouth yawns and yawns. Like wings, her chador

unfurls over a bare, bleached street. She looks

almost like she’s flying, one leg cut off

by the photo.

Though plenty of gestures here point toward the impossibility of connecting the two scenes, including the way “one leg cut off” summons an image of dismemberment before “by the photo” arrives on the other side of the break, those moves feel too easily managed to embody the distances Metres means to cross. It’s in the poems where he is least visible that the asking turns profound.

The book’s title, Sand Opera, is an erasure of the phrase “Standard Operating Procedure,” an attempt to scratch poetry from the routinizing of gruesome acts (and to use the tools of government cover-up in the service of exposure). According to an interview with the Vatican’s official radio station, “the book began as a Lenten practice, in which Metres read and meditated on torture testimonies from Abu Ghraib prison.” Metres told the interviewer that “the torture itself echoes for me … the great pains that Jesus endured and His death.”

There’s a worrying irony in approaching the torment of (mostly) Muslims in Christian terms. But as Metres suggests, his religion is here as practice more than doctrine, a form of devotion that calls him beyond himself. In the book’s first section, “abu ghraib arias,” redaction cuts two ways: It applies a tool the government has used to hide the suffering of prisoners and registers the power and reality of the prisoners’ voices, which strike against their abrupt termination with stunning force. Surrounding that, somehow, a profound and terrible calm presides, a slowly coalescing image of Metres’ devotion in arranging these words. The prisoners’ testimony gets harder to ignore because it is so audibly obscured and so patiently arranged, as are the other sources, including the Book of Genesis, which waver between embracing these voices and repeating the authority that wipes them away:

There are plenty of other voices, too, including those of the people responsible for the torture. Metres subjects many of them to erasure as well:

they removed their hands

……………………………………

………….I watched as the night

……the rest of them

These omissions imply a missing accountability, the unvoiceable black rectangles reenacting violence. More voices keep coming—as do a variety of visual forms: transparent pages laid over other pages, maps of torture cells. At times the book sprawls, and often such sprawling feels essential, as does the strangeness of it, the book’s partial speakers estranged from our usual ways of making sense. Sometimes they stretch toward a terrifying dignity (“until I was / laid upon the altar”) before collapsing back into horrifying pain (“the stick that he always carries inside / me”). Sometimes they are shredded, like the martyred body of St. Bartholomew, of which Metres writes in Sand Opera’s first poem,

scissored out hymn / & if

the body’s flayed & displayed

in human palms / & human skin

scrolled open / the body still dances

Photo courtesy Kent Ippolito

Reading these poems alongside Emerson’s, I often wondered what would happen if you swapped the two poets’ styles. Could an approach like Emerson’s record the rendings our apparently seamless American lives involve? Could Metres’ disruptions and distortions do justice to the hard-won continuity of Emerson’s beautiful mind?

One of Emerson’s poems, a dramatic monologue spoken by the widow of a once-famous Sicilian embalmer, Alfredo Salafia, ends with a recollection of pressed wildflowers:

not the stuff of memory unless

I write the hour we sat on a bench of stone,

parrots making green screaming ribbons of the air

above us; I wanted something to remember it by,

some small memento I recall hesitating

to take from its one afternoon of pollen

and bees—color its one remaining trueness,

shape collapsed, thinned as paper—this preserve

a worse kind of withering, perhaps, and yet

you see how I again have turned to it

for its very failure to compare.

That “failure to compare”—coupled with a passionate, persistent, clear-eyed refusal to be satisfied with it—may be art’s best answer to our own and others’ vulnerability. It feels inadequate in the face of the death of one poet, much less the torture of thousands. But perhaps that’s the point.

—

The Opposite House by Claudia Emerson. Louisiana State University Press.

Sand Opera by Philip Metres. Alice James Books.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.