Has B. Catling built a novel? As well as being a poet and novelist, Brian Catling is an English sculptor and performance artist, and this shows: He has not constructed a book so much as a happening, established the framework for a literary situation in which anything may occur. His novel The Vorrh is bold, shaggy, and surprising; often beautiful, arresting, or both. It has its problems, but they have nothing to do with timidity.

Trying to capture the essence of this book’s plot is like trying to snatch eels from a river with chopsticks. There’s so much going on, and most of it is slippery and changes direction even as you grab at it. Dozens of characters appear, and their stories writhe over and under one another, knotting into vivid clumps of imagery and event.

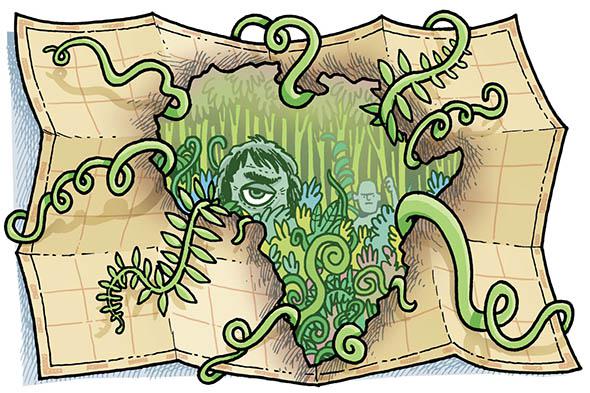

The book mostly takes place in and around the Vorrh, an uncharted and unknowable forest in Africa filled with John of Mandeville’s anthropophagi and other unknown monsters. It is said to hide the original Garden of Eden at its heart and be haunted by decayed angels; God may walk in its innermost places:

“The Vorrh was here before man,” he said. “The hand of God swept over this land without hesitation. Trees grew in its great shadow of knowing, of abundance. The old silence of stones was replaced by the silence of wood, which is not quiet. A place for man was made, to breathe and be thankful. A garden was opened at the centre of the shadow, and the Vorrh was given an occupant. He is still there.”

Ordinary people can only enter the Vorrh in the most limited of ways without losing their souls and becoming mindless Limboia. Europeans have nevertheless found a way to log the forest, and to expedite this, a city, Essenwald, has been brought stone by stone from Europe to be reconstructed within sight of the Vorrh. There is a sort of atmospheric tension between these two places, the forest and the city, like thunder in the air. Most of the characters vibrate in place or shimmy back and forth between them.

Here’s the start of one story: Ishmael is a perfectly formed one-eyed boy, raised in a sealed house in Essenwald by entities he calls the Kin, small brown (also one-eyed) carapaces filled with thinking cream. A young woman breaks into the house and meets him after killing one of the Kin.

Another story: Peter Williams is a young Englishman who came to a colonizing outpost in Africa after World War I. He saves a local shaman, Irrinepeste, who seems mad and is desecrating the new church by menstruating. Years later, she gives him the tools to become Oneofthewilliams, a mythic figure whose actions kick off the (undetailed) Possession Wars, during which the True People rise up against their colonialist oppressors. (Who are the other Williamses? Are there any? Unknown.) Years later and dying, Irrinepeste orders him to convert her corpse into a black bow and two shadowless white arrows:

I shaved long, flat strips from the bones of her legs. Plaiting sinew and tendon, I stretched muscle into interwoven pages and bound them with flax. I made the bow of these, setting the fibres and grains of her tissue in opposition, the raw arc congealing, twisting, and shrinking into its proportion of purpose.

The bow and arrows, semisentient, are instrumental to Williams’ quest, such as it is: He has crossed the Vorrh once and must cross it again. Williams is hunted by Tsungali, one of the True People, a former friend, and a tireless tracker—who is himself tracked by another mysterious figure, a Boundary Holder of the great forest.

Another story: the Frenchman (a real man, proto-Surrealist Raymond Roussel [1877–1933]), who has written a book, Impressions of Africa, without having been there: a fantastical mélange of exotic images and adventures. Now an aging sensualist, he comes to Essenwald and accepts a challenge intended to crack open his jaded soul: He will enter the Vorrh.

The book also follows historical figure Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904), the photographer whose zoopraxiscope presaged the moving picture—and whose long life, detailed through the book, ended decades before the novel’s main action. And there’s the Erstwhile, subsentient entities that may be decayed angels; a gray creature who may be Adam; ghosts; a hive mind of soul-dead slave laborers; a rare World War I pistol capable of stopping a running horse; a contagious miracle/curse—

The Vorrh is the first volume of an intended trilogy by Catling, and that makes this book even more slippery. By the end of this volume, many characters are dead or dead-ended—but in a novel with ghosts, what does that mean? The formal and informal quests driving some of the characters have changed and changed again, been lost or forgotten or inadequately completed. If an individual’s story feels underdeveloped or random, will the second volume fix that or just extend it? Is the plot going to advance in more conventional ways? Or can Catling sustain this level of weirdness over 1,500 pages and still trust his readers to stick with his vision? Will the story become more strange, or less?

None of this touches the heart of this book.

* * *

What this book is not, is about Africa. The Vorrh is a direct reference to and response to Roussel’s Impressions of Africa, a fantasia written in the 1920s that had nothing to do with the continent and everything to do with the same impulse to generate wonders that would subsequently drive Ernst, Carrington, and other Surrealists. Roussel’s Africa was a forest in which he could grow his fancies, a marvel-filled playground unrooted in reality. I am not convinced that a 21st-century writer can remake Africa this way. It cannot be treated as a blank place on the map; we as writers are confronted with a reality that is far beyond anything that can be imagined, a reality that already inhabits this geography. The True People, the tracker Tsungali, and the others do not convince me they are African so much as a set of (intentionally?) dated assumptions about colonial Africa; Peter Williams, the Englishman whose shaman spouse becomes a bow to his hand after her death, treads perilously close to becoming a white savior character, a Surrealist Kevin Costner in Dances With Wolves.

It’s also, weirdly, not about a forest. The Vorrh doesn’t feel real on the page: There are trees, but we mostly don’t know what they are (the only specific mention was of an oak, which I noticed because by this time I was pining for any concrete details at all). There is underbrush, but we don’t feel it. The only animals we hear about are the monsters that play directly into the plot and some birds. The Vorrh is meant to be impassable and mystical, but it almost never feels that way; instead it is a European-styled woodland with all the naturalism and danger of Brocéliande. This vagueness might be intentional, but it is annoying when I contrast it with Essenwald, which Catling so generously embodies.

Photo by Gautier Deblonde

The book is deeply preoccupied with vision, and monstrousness threads through this. The cyclops Ishmael is a monster who sees clearly and would be reviled if people knew of him. He leaves his smothering situation in the city for the Vorrh, expecting to find kinship with the one-eyed man-eating monsters that live there. In Essenwald, blind beggars are healed and become a different kind of monster. Creatures that can only be seen on a two-hour delay; objects that accept no shadow or swallow all light; eyes that endlessly flicker after death, even when removed from the skull—the very act and organs of seeing are problematic in a thousand ways across this story.

One of the myriad characters is Cyrena Lohr, a rich blind woman who gains use of her eyes after an encounter with Ishmael—and finds herself hating the ways that sight violates the calm of her eyeless life. In a stunning three-page sequence, she examines a vase full of peonies given to her by friends congratulating her on her newfound vision:

The petals curled and ruffled to catch any saccade and pull it in, so that a maximum density of viewing was folded in on itself. All human sight was sucked towards a central concentration, a habitual, swollen funnel, like the mouth at the centre of an octopus’s beak, demanding to be fed by all its arms. The blooms seemed designed for the eye, matching their craving to humanity’s visual gluttony; they even mimicked its anatomy, once the external ball was peeled away. A dozen or so of the bright, rumpled orbs moved at a speed concealed from her hectic eyes. Others stirred more positively, picking up the passing breeze, nodding in what seemed like a smug, taciturn agreement among themselves. Their vanity appalled; she could see the strain of opening as they demanded to be seen, the hinge at the base of each petal bending under a pressure, stressing until they fatigued and fell loose, leaving a swollen, pregnant overy. That was the extent of their purpose: to gush colour and expose the wrinkles of their complexities; to attract admiration and excited insents and perpetuate the fertility of their kind.

The more she looked, the more she saw the extravagant blooms as an insolent, mimicking raid on her eyes and a mocking sham of her womanhood.

Cyrena has grown to miss the cozy, unseen world she used to live in. In that world, the sounds of flying birds and bats were perceived as a wonderland of unexpected pops of noise scattered around her; with sight, this wonderland deteriorates into animals following predictable paths as they go about the quotidian business of finding food. As for these peonies, their invasive visual demand to be prioritized over anything else disgusts her so greatly that she closes her eyes tightly, returning to her old unsighted world, and carries their vase across the room to drop over an unseen balcony.

Also part of this is the devices of indirect vision: things seen in the corners of the eyes, things seen at a distance in time or space. There is a camera obscura in the cyclops Ishmael’s house that can see all of Essenwald as miniaturized reflections on a table. Muybridge’s photography is of course a way to visually preserve a thing for a later time, and his zoopraxiscope and other experiments with moving pictures were focused on breaking movements through time into static images that could be interpreted. Halfway through The Vorrh, Muybridge and the real Victorian Dr. William Gull experiment with devices that use flickering lights and peripheral vision to elicit automatic physiological and emotional responses like anger and orgasms. In this book, what is seen cannot be trusted, but not in an Is it Photoshopped? kind of way. Vision can trick you into doing things that have nothing to do with sight; pictures and images are by their very nature fakery. Time can be gamed; so can space.

* * *

So what is the heart of The Vorrh? I speculate that it lies not in the contents of this novel but in its nature.

The book begins and ends with the Frenchman’s story. In a posthumous work Roussel revealed that his books, including Impressions of Africa, were produced according to elaborate formal constraints. His work was widely admired by the Surrealists and Oulipo, movements that challenged conventional narrative techniques and expectations. The Vorrh is Surrealist literature in the best old-school sense of the word. Much of its energy comes from Catling’s unwillingness to commit to any of the classic narrative strategies he toys with throughout—the quest, the hunt, the love story, the Bildungsroman. And the rest of it—the arbitrary character changes, the out-of-the-blue insertions, and the apparent dead ends—creates a sort of Brownian motion, a vibratory narrative energy that does not advance so much as shimmer. Is The Vorrh also constrained literature? I write a lot of constrained literature, and I suspect that it is, though I could not guess the rules.

I was reading The Vorrh during a visit from a friend who is an artist, so I read most of it aloud to her. This was a good thing. A book read aloud exists inside time, rather than outside it. You cannot simply skip past or ignore the hard parts; if it is Surrealist, you have to stick with the moments of dissonance, process them at exactly the same speed you work through the more conventional pages. We stopped often to talk through the book’s confusions—and to note the many, many instances of breathtaking language, the often-playful chimes and rhythms and rhymes. (Beauty also becomes more obvious at the speed of sound.) There was an entire chapter so clean and lovely that I wanted to turn back and read it again—Chapter 25, if you are playing along at home. My third-floor apartment has huge windows that open into the upper branches of an urban forest (mulberry and oak); I read until the days faded into darkness, and my voice grew hoarse.

It is possible that this is the reason for this book: the immediate jolts and delights of each scene, to be experienced in the order they appear, without worrying about the total panorama. This makes reading The Vorrh rather like walking in a dense forest with short lines of sight—always another turn, always another tree—many small delights and terrors, and then those occasional sweeping moments when the trees fall away for a view that suddenly reminds us of the immensity of the landscape.

—

The Vorrh by B. Catling. Vintage.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.