In the late fall of 1974, the director Werner Herzog got a telephone call with the news that his friend and mentor, the German film critic Lotte Eisner, was dying. Herzog’s reaction was characteristically extreme: “Our Eisner mustn’t die, she will not die, I won’t permit it,” he wrote at the time. “She is not dying now because she isn’t dying.” Typical Herzogian anti-logic dictated that an event of such symbolic power must be answered by actions of equally symbolic strength: Ergo, like Christ entering the wilderness, trusting that through his suffering salvation would be gained, the young filmmaker determined to walk from his home in Munich to Eisner’s deathbed in Paris. Taking a duffel bag, compass, and a pair of brand new boots, he undertook a 600-mile pilgrimage in the depth of the German winter, between Nov. 23 and Dec. 14. In full faith, Herzog explained, he believed that this coming on foot would keep Eisner alive. “Besides,” he added, “I wanted to be alone with myself.”

Herzog undertook this shamanic journey, maybe, less to stave off the death of a friend than to confront himself in the liminal space between life and death, reporting back to us, as he so often does—on the rim of the spurting volcano Soufrière or in the Venusian landscape of a Kuwaiti oil field—from the edge of disaster and doom. As long as he walks, he remains in between, testing the boundaries of where one is supposed to be. He records a world fraught with the kind of portents and dismal signs that elevate his quest, situating it as muscular legend.

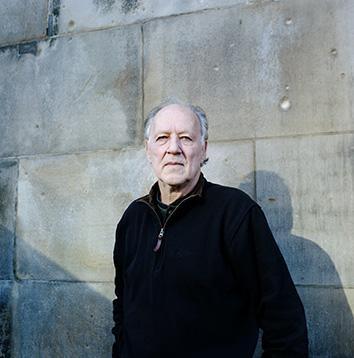

Herzog’s private diary of his journey (or at least what he claims as one; we have only his word to go on) was first published four years later on. Titled Of Walking in Ice, it’s now being reissued by the University of Minnesota Press. It is a weird and wonderful document—a vital record of Herzog’s creation of his famous, baffling self. Reams of commentary on Herzog have been published since 1974, by himself not least, and here, as elsewhere, it is hard to separate the man from the myth. In the book, one can watch as he collapses, in his very person, the boundaries between the biographical and the aesthetic, as he’d go on to do again and again in his films and public persona. The voice too is the one we know so well from the films and summons the familiar face: lugubrious, disheveled, and beetle-browed, perennially squinting as though against the blinding light of the universe’s final catastrophe. No detail is too small to depress him: “The teenagers on their mopeds are moving toward death in synchronized motion,” he glumly writes. “I think of unharvested turnips but, by God, there are no unharvested turnips around.”

Part of the physical trial of walking is what Herzog calls “dreaming on foot”—travel in this way becoming less a means of locomotion than a way of being in which fact and fiction can merge. Of Walking in Ice veers without notification from geographic document to apocalyptic dream, from hallucinations of war to the plots of films not yet—or possibly never—made. The final scene of Stroszek is dreamed here too, as is the chair-bound father who appears in Heart of Glass. Herzog’s characters emerge—Bruno S., Kaspar, Woyzeck, the ski-flyer Steiner. Passing buses and buildings inspire elaborate back stories, tales of death or loss that the solitary traveler would have no way to know. In walking, eidetic fictions merge with the facts of the landscape, and this mingled vision becomes the walker’s truth.

Living through dream is hardly a task for the weak, and seems undertaken for precisely that reason. Consider the title of Les Blank’s film about the making of Fitzcarraldo—Burden of Dreams—and Herzog’s declared readiness to make that film, or perish. Here and seemingly in every project he undertakes, Herzog is willing to extinguish himself in the making real of his vision. Each film of his comes with a story about the danger and suffering undergone by the director, cast, and crew. Where this did not exist naturally, Herzog would create it: Jumping into a bed of cacti after finishing Even Dwarfs Started Small, threatening Klaus Kinski, eating his shoe. In Of Walking in Ice, he attempts to match his actions to the spectacular winter landscape through which he travels, the limitations of which he presses against, the magnificence of which he seeks to equal. In doing so, he is alone: “Everywhere the forest was staring, vast and black and deathly, rigidly still,” he writes. “A loneliness like this has never come over me before.” He avoids contact with others and seems presented with an endless succession of empty homes in which to spend the night. “The villages feign death as I approach.” Here he’s an outsider in a hostile environment: He’s a thief, a criminal, creeping through broken windows in the dark. Breaking and entering, he sleeps in empty beds and dries his face on unwashed rags. He is set apart from human beings, just as he is from nature—both are symbols to him. This, it seems, is the cost of genius.

Herzog has often said that the goal of his films is what he calls “ecstatic truth.” He uses the German word erhabenheit—a descriptor that refers, literally, to something raised above something else, like the embossed letters on a credit card—to describe his ideal of a state of sublimity through which one gains access to deeper truth. This state, in Herzog’s telling, is antithetical to pure fact—a claim that can’t help but make me suspicious of his diary’s legitimacy as such. “My steps are firm,” Herzog writes. “And now the earth trembles. When I move, a buffalo moves. When I rest, a mountain reposes.” Of Eisner’s death he thinks: “She wouldn’t dare!” What seems like magical thinking (the idea that walking will save Lotte Eisner) is Herzog’s way of forcefully realigning the world with the way it’s experienced by him. His actions are symbolic, of course—in this way, they are elevated above the world of nature and man, the reality of which is subsumed into his doomy, eidetic consciousness as he goes.

The book is steeped deep in the German Romantic tradition, where experience itself merges with the aesthetic, the arduous, Beethoven-ish process of creation imbuing an artwork, or action, with a value that reaches into the sublime. Ravens croak in the fog. His new boots cause blisters. He rubs brandy on his frozen thighs, eats bags and bags of tangerines, and drinks milk until he vomits. He buys himself a hat, an item of clothing he finds “utterly repulsive.” The cruelty of nature, while it ruins him physically, rouses him as well—he is elevated. Of one of the many snowstorms he encounters along the way, he writes:

I am a ski jumper, I support myself on the storm, bent forward, far, far, the spectators surrounding me a forest turned into a pillar of salt, a forest with its mouth open wide. I fly and fly and don’t stop. Yes, they scream. Why doesn’t he stop? I think, better keep on flying before they see that my legs are so brittle and stiff that they’ll crumble like chalk when I land. Don’t quit, don’t look, fly on.

Like ski jumping, the walk is, as Herzog sees it, a way to fling off the usual protections—an expunging of consciousness so complete that all that remains behind is a kind of ecstatic joy.

Ski jumping was the subject of The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner, Herzog’s first documentary and the first time the director put himself in a film. It is, according to its director, among his most important. Released at the start of the year, 1974, in which his journey to Paris began, it provides an enlightening companion to Of Walking in Ice. The film, Herzog’s version of sports reporting, deals with Walter Steiner, a woodcarver by trade, who was at the time among the foremost “ski flyers” in the world. It opens with the image of the red-capped Swiss launching himself into the snowy void in slow motion past a dark curtain of trees. Slowly, he comes nearer, until his body fills the frame. Jumping, Steiner goes beyond the point to which one is supposed to go; he pushes against the laws of nature in order to achieve the impossible dream of flight. In this, Steiner, as Herzog says in the book-length interview Herzog on Herzog, is the brother of Fitzcarraldo, that opera-obsessed rubber baron (played by Kinski) whose mad genius led him to haul a steamship over a mountain. He is also, by that logic, the brother of Herzog himself, who, famously, did pull a steamship over a mountain, merging, in that way, with his character. But even more than this, Steiner is, in his leap into the abyss of solitude and madness, the double of the walker in Of Walking in Ice. Both offer examples of what Freud might call a “death drive”—a willing effacement of the world and risking of self through a sort of narcissistic faith in one’s own vision. Absolute solitude is death. It is also absolute control and absolute freedom and, for Herzog, a kind of sanity: Alone, he is the sublimely rational one, his faith realized and rewarded. “No one will know what this journey means,” Herzog writes, and this seems at least a part of why he undertakes it, as though physicalizing the existential solitude with which he’d already, even so early on, aligned himself, with characters like Aguirre and Kaspar Hauser. Around him, a monumental landscape unfurls itself, disastrous, divine, and wreathed in spirit.

Courtesy of Werner Herzog Film

This is what’s easiest and most impossible to mock about Herzog: the seeming honesty of his hyperbolic awe, the straight-faced mystic sensibility that gives his early narrative films and his documentaries—in their long silences, juxtapositions of image, the intoned dialog aimed at no one—their counter-intuitive power. Like his countryman and contemporary W.G. Sebald, Herzog seems to be witnessing from some lonely realm, one filled with untold horror and beauty. He’s feeling about in the places where the universe ends and coming back, weary, if slightly amused, to tell us about them. Stylized melodrama and a familiar lack of ironic distance make frequent appearances in Of Walking In Ice: “The universe is filled with Nothing, it is the Yawing Black Void. Systems of Milky Ways have condensed into Un-stars. Utter blissfulness is spreading, and out of this utter blissfulness now springs the Absurdity. This is the situation.” The effect is amplified by the fact that the translators have seen fit to preserve that Germanic grammatical tic of capitalizing important nouns.

Herzog’s prose—his very self—has to be considered performative. But where these kinds of excessively earnest pronouncements are, in his films, verified in some way by the gorgeous imagery behind them, here they sit stark and remorseless on the page. Much of Herzog’s appeal, and his power, revolves around his personal physical drama, his stubborn placement of himself on the edges until the edge becomes the center by force of his personal magnetism, or stubbornness, or endangerment of himself, and this physicality is harder to achieve without image.

Herzog ended Woodcarver Steiner with a quote, attributed to Steiner but borrowed from a story by the Swiss writer Robert Walser, another great walker, and one who, like a Kaspar Hauser or a Klaus Kinski, danced on the lines between solitude, genius, and insanity:

I should be all alone in this world. Me, Steiner and no other living being. No sun, no culture: I naked on a high cliff, no storm, no snow, no streets, no banks, no money. No time and no breath. Then I would no longer have to be afraid.

Afraid of what? One might wonder. Of the impossible, maybe. In the last shot of the film, Steiner flies on his skis against an unblemished backdrop of white, and it looks like he might keep going forever. “Is the loneliness good?” Herzog asks himself in the diary. “Yes it is. There are only dramatic vistas ahead.”

By the time Herzog arrives in Paris, it is Eisner who is at his bedside, the exhausted traveler slightly embarrassed, but, maybe, no longer afraid. “Open the window,” he tells Eisner from his chair. “From these last days onward I can fly.” It’s a proclamation of an achievement of faith, this, the impossible reunion, in his tired, weather-beaten person, of vision and the real. As it turned out, Herzog’s magic, as it so consistently, so irrationally, and so unexpectedly does, worked this time too. Eisner recovered, and lived for another nine years.

—

Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog. University of Minnesota Press.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.