The most important thing to understand for a listener new to “modern” art music—the thing I’m always trying to impress upon those patient souls who let me drag them to such concerts—is the need to shift their paradigm of judgment from beautiful/ugly to interesting/boring. To approach much of art music after, say, WWI with beauty as one’s primary criteria for liking something is to misunderstand the motivations of many of the most prominent composers working over the past century. For many 20th- and 21st-century composers, the working out of compositional processes—dodecaphonic series, mathematical formulae, grand minimalist arcs, etc.—is an end in itself, and composition is a quest for ingenuity and freshness of construction, rather than attractiveness to the ear. This is why listening to the music of our era requires a certain amount of work. To appraise it fairly, you’ve got to try to understand what formal element or problem the composer was trying to address—only then can you reasonably decide whether or not she succeeded, whether or not the work is compelling.

Philip Glass is a master of the sort of music (sometimes thrown together under the imperfect label “minimalism”) in which subtle formal processes play out over the course of the piece; that his harmonic language usually hews to a familiar tonality has meant that many casual listeners miss the scaffolding for the bewitching facade. But to really appreciate what Glass is up to in his works—some of which are viscerally captivating and others of which feel like the repetitive ramblings of a drunk or cokehead, tempo depending—you’ve got to make the effort I describe above to attempt to understand his artistic intentions. As it turns out, it’s not just the music that benefits from this approach—so too does Glass’ new memoir Words Without Music.

Glass’ intentions in this book are difficult to discern at first. While reading I often wondered if the composer was really interested in writing the book at all, given his seeming detachment from much of the material. In certain passages, there’s a feeling that an editor’s prompting—But didn’t you feel anything about that event, Phil?—has only just been excised from the text. But there is a deeper process at work. By my reading, Glass is using Words not to unburden himself or cement his place in musical history but as an exercise in self-mythologizing. Stick with the digressions and associative time-jumps long enough, and you’ll start to feel that Glass wants to convince us—and perhaps himself—that he is a certain kind of person possessing certain laudable qualities. But, as is the case with most attempts at autobiographical PR, contradictions quickly emerge—and it’s these that provide welcome notes of dissonance to an often bland score.

The most consistent of these friction points is the question of origins, a sort of Phil-from-the-block anxiety. Glass composes serious art music; since entering the University of Chicago at age 15, he has moved (taxi-driving and plumbing day jobs notwithstanding) in relatively rarefied circles. But Glass, the child of a librarian and record-store owner, was the kind of kid who was tasked with helping Dad watch out for shoplifters in the store’s “low-rent” Baltimore neighborhood, and he strives throughout Words to coax some kind of folk authenticity from that background. Of a childhood fight precipitated by the fact that Glass’ flute lessons made him seem gay, he writes: “The kid could have been six feet tall and I still would have beaten him, it didn’t matter. After that, no one bothered me about the flute.” Despite these earthy reminiscences, Glass’ connection to his home and family (and indeed most personal relationships) feels strained—he notes on a number of occasions, for example, how his mother was “mystified” by his work and writes strangely cool sentences about her. (“Ida was a very interesting woman.”) While other successful artists might try to forget their humble origins as quickly as possible, Glass seems fixated on finding some value in his—even as he shrinks from their roughness on the next page, as he does from his Dad’s readiness to “pulverize” thieves.

There’s similar ambivalence in Glass’ relationship to judgment among his fellow music professionals. Take this statement of independence, given in response to early vitriol directed at his operatic masterpieces Einstein on the Beach and Satyagraha: “They were going to be mad at me no matter what I did. But luckily I have a wonderful gene—the I-don’t-care-what-you-think gene. I have that big-time. I actually didn’t care then, and to this day I still don’t care.”

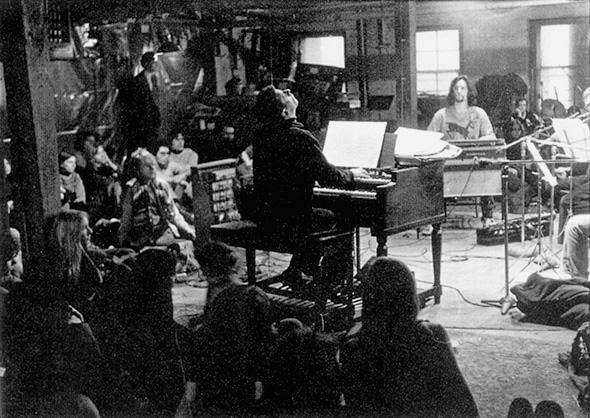

Photo by Steve Pyke

But, in fact, Glass cares a great deal about what people—at least certain people—think; indeed, he feels most human when reflecting on his teachers and collaborators, individuals like Ravi Shankar (whose instruction in Indian musical traditions was pivotal in the development of Glass’ approach to rhythm) and Richard Serra for whom he holds an unexpected reverence. Words is in many ways a recounting of influences, and the best parts are explicitly about the relationship between student and teacher. If Glass decides to write more words, he might expand upon his time with the famous French technician and pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. The section devoted to their time together in Paris is by far the warmest and funniest of the memoir, as if the pull of her charisma drew a little color into the pallor of Glass’ prose. Of a particularly daunting exercise demanded of a randomly selected student each week, Glass, in a sort of bemused respect, writes: “God help you if you weren’t prepared or, even worse, not present. If she was expecting you to be there and you didn’t show up, you probably would just have to leave town.”

These sorts of tensions manifest in other arenas: Glass returns often, for example, to the space between the art and the business of music since he, as the founder of a record label and publishing company, is firmly engaged in both pursuits. His comfort with identifying as something of a workman rather than a solitary genius is genuinely refreshing: On the subject of taking commercial jobs, he writes, “I thought this selling out idea was a bizarre notion. It seemed to me that people who didn’t have to sell out … must have had rich parents. ”

But the conflict I found myself tracking more than any other was Glass’ sense of himself as a serious musical thinker against the notion within certain regions of the art music world that, because some of his music sounds “easy” or derivative, he might be, as he puts it, a “musical dunce.” A rare flash of anger in that regard:

I think they thought I was teasing them, trying to make fun of them, which was a ludicrous idea. Why would I go all the way to Europe to make fun of a bunch of yokels there who didn’t know anything about world music or even new music? They hadn’t spent time with Ravi Shankar. They hadn’t gone to India. They hadn’t made the journey I had, opening myself to all different sounds of music. They didn’t know anything.

These ignorant Europeans didn’t understand Glass’ music, but, more important, they didn’t appreciate his credentials, his pedigree. And for a man who is so deeply invested in a notion of cultural transmission and reinvention over time, lineage—and the respect that lineage should confer—is everything.

This, in the end, is Glass’ argument, the story of himself he wants to tell: that his music, though generally simple in effect, is thoughtful in conception and a natural and worthy product of a unique and enviable lineage. Does he make it well? As someone who generally admires Glass’ musical approach, if not every work, I think it’s correct to say that his oeuvre is more complex, historically situated, and widely influential on the whole than he is always credited for.

Does that argument, presented in the guise of autobiography, make for a good memoir? Of that, I’m less sure. But maybe that’s not the best question. For Glass, the point is always process, the doing of the thing, more so than the result. And keeping that in mind, I’m inclined to let him define success here in his own terms: “If you don’t know what to do, there’s actually a chance of doing something new. As long as you know what you’re doing, nothing much of interest is going to happen. That doesn’t mean I always succeeded at being interesting. Sometimes I did and sometimes I didn’t.”

—

Words Without Music by Philip Glass. Liveright.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.