It seemed like sensational news to me. I’m not sure why it hasn’t become more of a high-profile issue in literary circles. I found it to be—in the words of Mary McCarthy’s awestruck review of Nabokov’s Pale Fire—“A bolt from the blue.”

After all, this is a revelation about the mind of Lev Nikolaevitch Tolstoy. That Tolstoy, you know, the Russian novelist? Conventionally credited with being the greatest illuminator of the human experience in literature? The same one who—and fewer readers are aware of this—late in his life turned into a sex-hating crank who (seriously) argued that the extinction of the human species would be a small price to pay for the immediate cessation of all sexual intercourse. Everyone, everywhere. You there, hiding in the shadows: Stop fucking now!

And fewer still are aware of Tolstoy’s devastating “consolatory” response when it was pointed out to him that cessation of all sex would mean the rapid extinction of the human species.

He replied with what might be the single worst attempt at “consolation” in all of literature, perhaps all of life. What’s the problem with human extinction? Tolstoy asked. After all, science tells us the sun will eventually cool and all life on Earth will die off anyway. Sure, billions of years in the future, probably. But there’s actually a bright side to near-term extinction, he said: It will mean the human race will be spared billions of years of shame, billions of years of further degradation in what he charmingly called the “pigsty” of sex.

Glass half-full!

Seriously. Yes, it’s shocking, especially from a novelist whose works are known for their superb vitality, bursting with the love of life. And yet, far less well-known are his late anti-sexual novellas: The Devil, Father Sergius, and, most vicious, venomous, and sex-hating of all, the 100-page The Kreutzer Sonata. It’s a deceptively innocent title for the heartwarming story of a madman wife-murderer who delivers an interminable monologue on an interminable night-train journey across the Russian steppes. Who horrifies his captive audience—the passengers in his compartment—with a denunciation of men, women, and sex. Who thereby—in his mind—justifies the bloody murder.

Oh it must be ironic, said the Moscow-to-Petersburg Acela corridor chattering class of the time. He was portraying a character. True, his protagonist was a wife-murderer who’d been freed on judgment that he’d been driven to kill by justified defense of his “honor.” But Tolstoy himself was not justifying the murderer’s rationale for his act. Impossible!

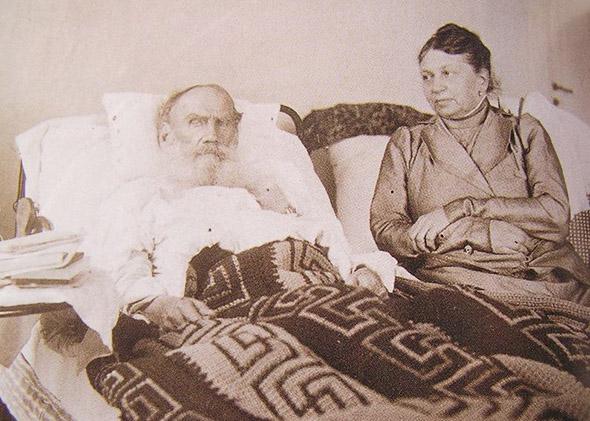

No, NO! thundered Lev Nikolaevitch in a “Postface” he insisted be added to Kreutzer to clear things up: He stood behind every word of the madman’s rationale, if not his final bloody act. Lev converted to a radical form of “primitive Christianity” in the 1880s and found an affinity with an anti-sexual sect that advocated voluntary castration. (He did not volunteer.) He hadn’t gotten around to killing his own wife, but clearly he could understand, he could empathize with the logic of the deed. Human love and sexuality were irredeemably evil; women were sinister provocateurs of male murderousness. (I am generally opposed to biographical criticism, but it’s worth reading The Last Station, Jay Parini’s historically based novel about the last days of Tolstoy’s bitter marriage—just to see how emotionally murderous that marriage was in the decade before he died in 1910.)

None too surprisingly, Tolstoy’s wife, Sofiya, took his tale of a wife-murderer personally, especially since it seemed to her it was inspired by the “issues” in her own marriage. The Kreutzer narrator—a Tolstoy-like landowner—fantasized an adulterous tryst between his wife and the violinist she played duets with. Mad sexual jealousy. And then when he comes home one night and unexpectedly finds the two dining together, he imagines the worst and stabs her to death.

It was fair to say Sofiya was humiliated and incensed when the novella was published and her marriage to The Great Man became suspect, subject to nationwide speculation. (And yet such was her devotion she made a special plea to the Czar to allow its publication after Orthodox Church objections banned it. In an unusual moment in the annals of censorship, the church objected not so much to a surplus of sex in Kreutzer, but rather to its denunciation of even church-sanctified marital sex as legitimized depravity.)

For a long time, it had been thought Sofiya kept her dismay to her private diary. But now—and this is the revelation I first saw reported in the New York Times last summer—it turns out she wrote an entire novella of her own that has languished unpublished and untranslated in the depths of the archives of the Tolstoy Museum in Moscow for more than a century.

And what a novel it is! Just published for the first time in English in a translation by the scholar Michael R. Katz, it appears in a Yale University Press edition that includes not only Tolstoy’s original Kreutzer, not only Sofiya’s “answer novel,” not only a response document from Tolstoy’s son and from his daughter, but much more. The volume is called The Kreutzer Sonata Variations.

It has not been established whether Sofiya ever wanted the 90-page novella published, or was content to let it remain a silent reproof in her possessions. In any case, evidence of how she felt about her husband’s depiction of their marriage in Kreutzer can be found in her list of possible titles for her novella:

Is She Guilty?

Murdered

Long Since Murdered

Gradual Murder

How She Was Murdered

How Husbands Murder Their Wives

One More Murdered Woman [or Wife]

Ultimately she chose a somewhat graceless alternate: Whose Fault?

So now, 125 years after Kreutzer’s 1889 publication, Tolstoy’s wife gets to have her say. It will take years to assimilate all the variations in Katz’s volume, but I want to focus on the single most impressive thing I found on my first reading: Sofiya Tolstoy can write! I’m still puzzled by the Times story’s somewhat cavalier unwillingness to consider her novella’s literary merit and even more by the subhead’s sexist characterization of her work as nothing but “a scorned wife’s rebuttal.” In fact, I think she’s good. At times one could almost say she’s … Tolstoyan. And when it comes to love and sex, she shows her husband up for the demented fool he became.

Specifically, Sofiya pulls off a remarkable structural feat in mirroring Kreutzer’s wife-murder plot from the point of view of the murdered wife. And she does it with prose that (in English at least) comes across as graceful, emotionally intuitive, and heartbreaking.

Thematically, she counters her husband’s rage against sex and love with what is, cumulatively, a deeply affecting defense of love. A portrait of love from a woman’s point of view unlike any you can find (or I have found) in Tolstoy.

Wait, you say. What about Anna Karenina? I’m glad you asked. I hope you’re not referring to the thin-blooded, gluten-free-wheat-field love raptures of Levin and Kitty.

Well, what about Anna Karenina and Count Vronsky? Tell me this. Was Anna in love with Vronsky, or in some kind of erotic thrall? It isn’t easy to decide, perhaps, because Tolstoy didn’t know the difference, didn’t understand the spectrum of feelings “love” can mean for a woman. As for Vronsky, he quickly fell out of any love he might have had for Anna once he had his conquest under his belt.

Indeed I was prompted to look again at the question of love and sex in Anna K by a conversation with the writer and Russian studies scholar Elif Batuman, whose brilliant and delightful book The Possessed recounts her travels with Tolstoyans and investigates the mystery of his marriage and death. She had a rather sardonic view of the single sex scene in the novel: that there really isn’t one. Anna and Vronsky enter a room for their first assignation. And, and, that’s all we get to know. Next scene has Vronsky getting dressed again while staring down at the prone and shivering body of Anna “as if he were a hunter gazing at a slain deer,” as Batuman puts it. “It’s not a sex scene, it’s a murder scene.” Love? Forget about it.

In Anna K, Vronsky’s only real love—almost sexual in nature—is for his horse. Seriously, reread the scene where he rides her to death in a steeplechase, for its almost scandalous description of the way the horse and rider, man and mare, merge into each other’s rhythmic movements. When he pushes her to jump too far, she dies from the leap, just like Anna does in her leap, in which she flings herself in front of the train.

Sofiya accomplishes something different in her novel, which, despite its defensive title, offers more than a he-said, she-said document. Instead, Countess Tolstoy counterpoises her husband’s mad denunciation of sex with a skillfully evoked account of the evolution of love. Love in all its facets, from the sexual to the familial to the fantasized adulterous. Love, in all its contradictory complexities and unresolvable mysteries, from a woman’s point of view. From inside a woman’s mind and heart, with a subtlety that makes her husband, Lev Nikolaevitch, look like a blockhead.

In the novella Sofiya gives us a touching portrait of a tender, hopeful young girl at first finding herself falling under the spell of an older man, an elegant-looking local landowner, a count like Sofiya’s husband. He’s not a successful writer, but he does seem to pen boring polemics she can’t really respect. He holds strong convictions, especially about sex and marriage. He’s very similar to the crank Sofiya’s husband became in his dotage—and almost identical in his opinions to the wife-murderer in Kreutzer. They are the opinions of an ignorant male presuming to be sophisticated about sex. (Fortunately we no longer have these types around these days.)

Behold sexual ignoramus Tolstoy, sermonizing to us in Kreutzer about his hydraulic, pneumatic, steam-engine gasket theory of male sexuality. “Pressure,” he writes, builds up and must seek “relief.” (“Relief”—his charming word for his attentions to his wife, with no regard to her needs. Her relief only comes when he falls asleep.) Unsurprisingly, as its wife-murderer-to-be Pozdnyshev looks on women as nothing but an instrument for man’s pressure-gasket release of steam, Kreutzer offers no sense of the interiority of women. And it sees sexual passion—the sexual pressure cooker—as a terrible evil against which men must struggle to avoid shame and degradation, even when the passion concerns one’s lawfully wedded wife.

Anna’s narrative in Sofiya’s novel offers us something else entirely. The woman in Whose Fault? reveals complexity, conflictedness, perplexity. During courtship, when the murderer-to-be first kisses her, “she feels a wave of passion such as she had never experienced run through her body.”

And yet for a considerable time after marriage, she refuses to have sex with her husband. She is fearful of the unknown. It doesn’t seem logical, but there is an awareness in the character Sofiya draws of the complex entwinement of love and sex. She ultimately succumbs, with a briefly mentioned docility, to “relations” with him. But she finds herself almost horrified, in a detached way, by her body’s response, and even more repulsed by the brutal, utilitarian nature of her husband’s attention. Even after his momentary pressure gasket relief, he is never peacefully sated, but actually becomes angry and hostile at the way he has degraded himself. What fun for Anna!

And yet, and yet. She finds love in the family situation, primarily love for her children and, dutifully, some kind of love for her husband. It is enough at first.

Enter Bekhmetev. He’s an old friend of the husband, has been out of the country because of illness. Frail, gentle, he likes drawing and conversation. His “chivalrous politeness, propriety, respectful admiration” of Anna allows him to “completely yet imperceptibly enter” her “familial and personal life,” without—at first—arousing “the Prince’s vicious feelings of jealousy.”

A sly dog? Not from Anna’s point of view.

It is here, with extraordinary delicacy, that Sofiya begins to evoke the intangible boundary between platonic and romantic love. The love her heroine starts to experience is nothing like the hectic headlong Eros of that other Anna, Karenina. (It seems likely Sofiya has not chosen the name Anna accidentally. It’s almost a challenge to his Anna.)

What Sofiya succeeds in doing in her novel is to counterpoise, to her husband’s inability to conjure love, her own utterly different vision. Is it one unique to women? I like Flannery O’Connor’s line in this context: “Everything that rises must converge.” The beauty of Sofiya’s novel is in its moments of convergence or near-convergence, when unity between Anna and Bekhmetev seems imminent, so close. There are recurrent suspenseful moments of near-adulterous physical passion—love as a suspense story.

The high point, the moment of near-to-total convergence between Anna and Bekhmetev, is one of those rare instances in literature in which conversation can transcend words and merge spirits. It is the scene in which Anna and Bekhmetev exchange thoughts on the nature of infinity, not as mathematicians but as souls possessed by the same transcendent dream of limitlessness. He discovers she’s been reading “a classic author, Lamartine.” She says she’s taking great pleasure in the work and he asks if he can read aloud to her. (Smooth move.)

He picks a passage, and it’s not clear how he knows it, but she says, “That’s just where I stopped.”

The passage from Lamartine’s French is about night: how “night is the mysterious book of meditations for lovers and poets. Only they know how to read it, only they possess the key to it. This key is the infinite” (l’infini).

At this moment they both realize the implications. They both “possess the key” to the infinite. They both know how to read and translate the Book of Night.

He then says something dramatic that invokes the infinite, something about its wonder and terror: “And the relationship of night to the infinite, to l’infini—is astonishingly poetic. If one doesn’t believe in this l’infini, it’s terrifying to die.”

The stakes are now higher. The “key” they share is the key to life, to courage in the face of death. To love.

(It’s fascinating when you think of all the—let’s face it—windy, half-baked philosophy of life, death, and history Lev Tolstoy inflicts on us, to the point, in War and Peace, of obscuring the intensity of human feeling he can achieve, and does achieve when he stops his incessant lecturing. And fascinating that his wife is able to offer a glimpse of the transcendence his grand formulations rarely deliver.)

To return to Sofiya’s novel, it is no accident that, almost immediately after this infini moment, Anna’s husband senses something and begins his death spiral into murderous jealousy. He senses something but he has no idea what it could be and can only think that his possession is in jeopardy. He becomes tormented with jealousy, with hatred of the woman he wished to possess alone.

She notes with revulsion now his lust for her: “Along with this hatred grew his passion, his unrestrained, animal passion, whose strength he felt, and as a result of which his anger grew even stronger.”

It is here on this very page that Sofiya gives away the game, not explicitly, but leaving no doubt of the dynamic going on in her own matrimonial prison: “He didn’t know her, he had never made the effort to understand the sort of woman she really was. He knew her shoulders, her lovely eyes, her passionate temperament (he was so happy when he had finally managed to awaken it).”

“He knew her shoulders.” In Tolstoy’s world of glittering soirees, when he speaks of bare shoulders, it is metonymy for a woman’s naked availability. Her shoulders inflame Anna’s husband because he knows they will inflame other men. Filtering that through the realization that she is subject to carnal desires too (her “passionate temperament”) makes for an explosive mix in the man’s increasingly deranged mind.

So things progress. Anna is spending glorious summer days painting with Bekhmetev by the riverside, and at last Bekhmetev hesitantly discloses that he has more than reading to her in mind. His acknowledgement of her desirability is cloaked: “You know that if anyone falls in love with a woman like you, it’s dangerous; it’s impossible to stop halfway on the road to love; it consumes you entirely.”

This is, they both recognize, a transgression. Not merely an observation about “other men,” but a dramatic declaration that his own feelings have leaped from platonic spiritual bonds to passionate love.

And we’re told “he turns pale and gasps for breath.” His health, never good, seems to teeter on the brink of a breakdown.

She tries to be cautious and, in a highly charged moment of implicit Eros, this exchange ensues:

“But such demand of love kills it … ”

“How then, Princess, can love survive, that is, live for a long time?”

Forgive me. I couldn’t help making an anachronistic connection when I read “How then, Princess, can love survive.” Philip Larkin’s great poem on love, “An Arundel Tomb,” ends with the line “What will survive of us is love.” I’ve written here on Slate about the mystery implicit in that line—what is the “love” that will survive of us? It’s a question implicit in what Bekhmetev asks: What sort of substance is this surviving love, mortal or infinite?

Some spirit, Anna hastily tries to say, shying away from their physical closeness. “Oh, of course, only by a spiritual connection” can love endure.

Hesitantly, awkwardly, he ventures, “You think, a spiritual connection exclusively?” You have to feel a bit sorry for the poor guy.

“I don’t know whether exclusively or not,” she says, which admits the possibility their physical closeness could become closer.

Sofiya is incredibly adroit, suggesting in the subtext the undertow of the words and silences between them. There is an erotic charge to what they leave unsaid. Here, as throughout, Countess Tolstoy’s description of love rings true to the array, the changeableness, the spectrum of embodiments from physical to metaphysical human love can take.

And then, she tells us, “his glance … glowed inside her.” Another euphemism, but what a beautiful one, luminous and sexual.

I won’t pursue the details to their horrifying conclusion. Ultimately nothing physical is consummated; she’s too honorable. Her husband refuses to believe it. He murders her by hurling a heavy paperweight that strikes her forehead.

But if her surrogate must die, Sofiya lives on in this astonishingly skillful novella. The final exclamation point to Lev Tolstoy’s career.

—

The Kreutzer Sonata Variations: Lev Tolstoy’s Novella and Counterstories by Sofiya Tolstaya and Lev Lvovich Toystoy by Michael R. Katz (editor, translator). Yale University Press.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.