The writer Amanda Filipacchi has said that her past novels have haunted her. The fiction she wrote began to seep into her real life. For her previous novel, Love Creeps, she thought she invented a psychological disorder to plague her main character—an agonizing want of nothing—only to develop that very real problem herself as a symptom of her depression.

For this reason, she says she resolved to load The Unfortunate Importance of Beauty, her fourth novel, with nothing but “good things.” But the book, partly a meditation on the power of beauty, partly a roiling mystery, works its haunting in reverse. The real-life, personal details that Filipacchi injects into her story take on surreal forms, exploded to their most absurd and lurid representations. The daughter of the iconic 1960s model Sondra Peterson (who is given a special, bittersweet cameo in the book), Filipacchi grew up with beautiful people, whose looks she says she did not inherit. As a child, she underwent a series of almost-successful surgeries to correct her slightly crossed eyes. Family, friends, and strangers informed her that her jaw line was growing at a less-than-ideal angle. If she wanted, she could get that fixed too with an invasive surgery that has a long and painful recovery period. She declined. As she grew older, she wondered why beauty seemed to matter so much, even to people who ought to know better, all the while unable to resist its allure herself.

In her new novel, Filipacchi considers the temptation of superficiality through the romantic experiences of her two young heroines. Barb, a successful Manhattan-based costume designer, is heartbreakingly gorgeous. She’s so distractingly beautiful that she worries she’ll never be sure if a man loves her unconditionally. Whatever the depth of their ensuing relationship, his love will be forever tainted by the disingenuous origins of his initial interest. So she devises a screening process: She dons a fat suit, a frizzy gray wig, muddy contact lenses, and a pair of crooked false teeth. Predictably, when Barb approaches men at bars under her new cover, they treat her with indifference. Once she’s satisfied that a candidate is shallow, she sheds the disguise to unveil her svelte frame, her stunning face. Many of the men adopt sweeter tones after her big reveal, but one admits that he feels robbed by her dishonesty. When Barb asks what she stole from him he hesitates, casting around for a delicate way to describe the thing: “You stole … my opportunity to make a good first impression.” In fact, she handed him the best one imaginable.

Barb is also part of an unusually close-knit group of friends who have recently lost one of their number. Gabriel, Barb’s best friend in the group, flung himself from the 28th floor of his apartment building, citing Barb’s maddening beauty as his No. 1 motivation. The playful menace that gurgles beneath Filipacchi’s imaginative hijinks begins here, with Gabriel’s suicide note. He bids goodbye to this fair world in every traditional sense except one, ending impossibly: “More later, Gabriel.”

In his absence, the five remaining friends continue to hold their “Nights of Creation”—weekly sessions at Barb’s apartment during which they each commit time to their individual passions with one another’s company and support. Barb designs costumes; Lily plays piano; Georgia types her best-selling novels. Penelope tries to save her flailing pottery business and Jack lifts weights. Among them, Lily is the most naturally talented, but we’re told by Barb’s narration that she is also “inoperably” ugly. Among other misfortunes, Lily’s eyes are too close together—lovely on their own, but only when examined one at a time, as separate entities.

Lily’s spirit is not crippled by her appearance. She is a gifted musician. She is deeply loved by her friends. Then, as luck would have it, she falls in love with someone for whom looks are a deciding factor. Her friends are concerned. They see the beauty in Lily that others can’t, and they don’t want the jerk to dampen her inner life with cruel rejection. But when Barb begins receiving postdated letters from Gabriel in the mail, the group’s devotion to Lily’s happiness starts to look like the garish stuff of nightmares. According to Gabriel’s notes from the crypt, one of the five friends is a murderer whose next target is the object of Lily’s affection.

The dreamlike tale that ensues traces the intersection of beauty as it exists in the harsh light of public expectation and as it lives in the secret enclaves between individuals. In a scene in which Lily’s crush defends his preference for beautiful women (“If [a man] can’t get it up for her, what is he supposed to do, shove it up with a stick?”), Barb protests that attractiveness can present itself in singular ways—the way a person moves, the things she says, the stirrings of a soul. Both Barb and Lily test the limits of society’s fixation with aesthetic loveliness, determined to live apart from the reductive construct of conventional beauty worship. Barb cloaks herself in dullness and Lily plays truly exquisite music—her songs change the world around those who hear them, making ordinary things appear extraordinary, softening her own ugliness until she looks like an angel. Magic spills from the pores of Filipacchi’s story, and yet her characters warn against metaphors. The resulting romp is a witty and honest rendering of the unknowable distance between perception and reality, exploring the possibility that beauty is literally in the eyes of the beholder.

There is a harrowing moment late in the book when Barb is exposed, against her will, as a girl beneath a costume. After her ruse is caught on video and revealed to the public, she is swarmed by the media. They want to know why she tried to conceal her beauty, why she never pursued acting or modeling. In 2015, it’s hard to imagine that a viral video featuring Barb’s brand of performative gender politics would produce anything less than a maelstrom of social media polemics, her intellectual worth ground through the mill of attacks and counterattacks. She’d be lauded as a genius, feminist martyr, then swiftly dismissed as a counterproductive bimbo. No one would be all that interested in why she never became a model.

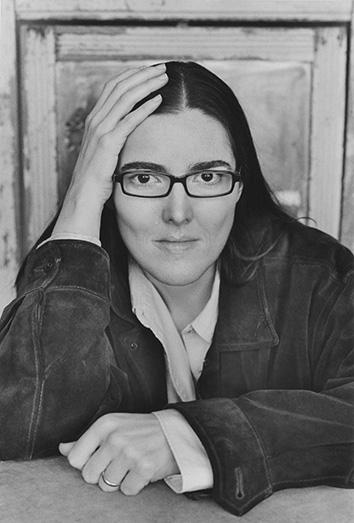

Photo by Marion Ettlinger

But Filipacchi’s viciously diametrical universe serves to underscore her characters’ central concern that encroaching, universal notions of beauty stifle its true quality. Indeed, the novel feels less like a straight satirical dismantling of the beauty-industrial complex than it does a joyous exploration of the limitless creative and intimate space that exists between Barb and Lily—between the obviously beautiful and the apparently hideous. It is the space in which Barb and her friends meet for their nights of artistic spontaneity and unfailing mutual support. Where Lily writes music with the power to transform everything, even her own most unfortunate features. Like lovers, isolated and unbound by convention in their own private world, the friends are blind to each other’s ugliest traits and moral failings. When Penelope’s pottery business suffers, she veers into fraud, breaking the clay pots in such a delicate way so as to create the illusion that they are intact. When customers visit the store and the pots shatter at their lightest touch, Penelope convinces them to pay for the broken items. Instantly, Barb finds a way to recast her friend’s poor ethics: “I wouldn’t be surprised if the art of deception becomes the true art of the piece.” Amid the group may lurk a murderer who, despite this pitfall, is encouraged by the rest to continue attending weekly sessions.

Filipacchi has said that she can see great beauty in physical ugliness. She and I are alike in this regard. I find it difficult to disentangle lines and shapes from the invisible forces that animate them. I’ve had the experience of staring at a person I love and wondering—seriously—whether I was seeing his face or the thoughts that fill it. Still, I’ll admit I found myself turning pages in time to the book’s thriller pace, desperate for the answers, at last, to old questions: Do looks matter? How much? Will I be loved for the formless person who swims inside of me as much as for the shell she brings to life? Filipacchi’s novel is an ode to both the tragedy and wonder of that uncertainty.

*Correction, Feb. 7, 2015, 2:57 p.m.: This review originally misidentified the title of Amanda Filipacchi’s previous novel. It is Love Creeps, not Nude Men.

—

The Unfortunate Importance of Beauty by Amanda Filipacchi. W.W. Norton.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.