Say you’re a grown-up who likes superhero comics but hasn’t kept up with them. Or else you want to like them or used to like them. Maybe you liked The Avengers or Batman Begins. Maybe you liked comics when you were 10, or 15, and now that you’re 29, or 69, or 15, you seek virtues you found in other art forms: reflective, slowly changing protagonists, meticulous world-building, or political thought. Maybe you’ve sought those virtues in current Marvel and DC titles; maybe, at times, you found them, only to give up after facing tangle of back stories, retcons, reboots, and crossover events. Or maybe you read the supposed apex of literary superhero stories, Watchmen, and threw up your hands: Its characters—delusional, cruel, or desperately ineffective— felt more like attempts to kill off a genre than like ways to give it new life.

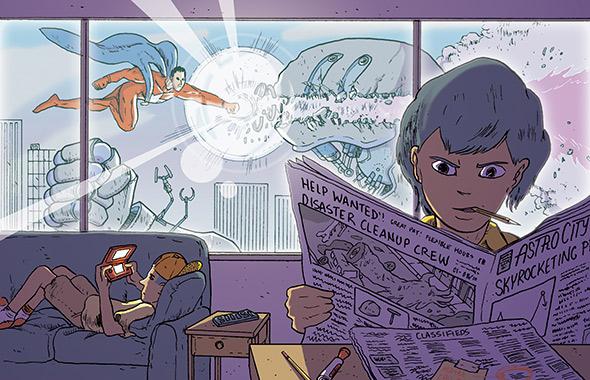

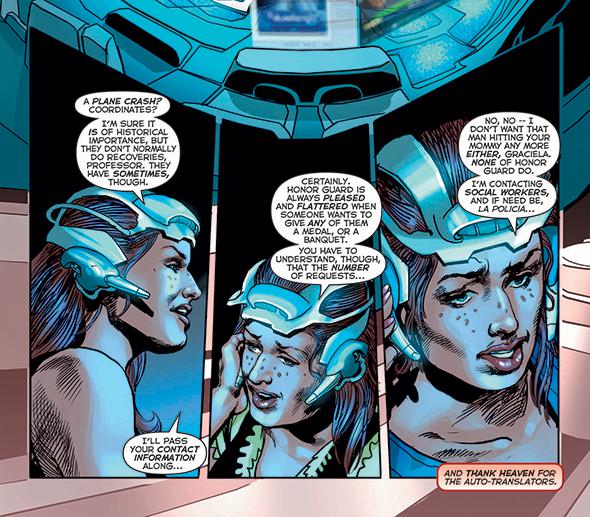

Fortunately for you, there is Astro City. Now in its 20th year and its 10th book collection (installments appear first as individual comics), Astro City is writer Kurt Busiek and artist Brent Anderson’s almost completely successful attempt to make stories that look like classic superhero comics but feel closer to literary fiction. The heroes of the Astro City universe punch monsters or collar superthieves, but the heroes of Astro City stories are just as often the non-superpeople who live among them. An elderly aunt operates a museum and rest home for discarded killer robots. A woman applies for “a call center job that’d maybe tide me over” and becomes a hotline operator for Honor Guard, the Astro City universe’s counterpart to the Avengers: “Spot a supervillain in your area? An alien incursion … You call us. We alert them.”

Image courtesy of DC Comics

Astro City is not our world, but it can feel close: Its trick is to pivot back and forth between situations we recognize from comics, and others that could come up in somebody’s life. A delightful arc (collected in the volume Shining Stars) follows Astra Furst, “the most famous girl in the world,” the day after she graduates from an Ohio college a lot like Oberlin. Astra owes her fame to her family, the First Family (think the Fantastic Four); potential employers shower her with offers, but, she complains, “They don’t want me—they want my name!” Real celebrity youth have her worries, but not her option—should she choose to exercise it—of a post-collegiate year in another dimension, with no paparazzi, meaningful work (repairing an inter-dimensional nexus), and butterfly-winged space-alien club-kid friends.

Astra’s journey sparkles and pops with planetary conjunctions, lightning whorls, airborne people in an aurora-strewn sky. Other settings in this series look almost mundane, or at least familiar: an Eastern European immigrant neighborhood, a glass-and-steel downtown. The United States of Astro City includes real cities like Boston and Las Vegas, and its history overlaps with ours: Sputnik went up, JFK became president, and the space shuttle Challenger (almost) exploded. But Astro City is also a city: If you want to live near lots of superheroes, you move there, and if you don’t, you move away. (Its landmarks bear comics-themed names: Mount Kirby, the Outcault Bridge.)

Comics history is American history: Astro City speaks to both. It is not, however, doomed to repeat that history. Samaritan—whose powers, costume, and visage recall Superman—isn’t Superman, Busiek insisted in a recent conversation: “He isn’t an alien, he didn’t come here as a baby, he’s not a reporter, he’s not from a farm.” Winged Victory isn’t Wonder Woman—she wears a helmet, she has giant eagle wings, and she runs a chain of women’s self-defense schools (which double as shelters). “She’s both angrier than Wonder Woman,” Busiek elaborated, “and more scared that she’s lost herself in her heroic identity.” On the other hand, she wears metallic bracelets and a Greek-inspired costume that shows off her legs, and she owes her powers to a magical island and an all-female “Council of Nike.” “I fight for women, backed by women,” she says. In the latest collection, Victory, she’s accused of colluding with villains and must decide whether to help—and whether to accept help from—boys and men: That is, she must choose between versions of liberal and radical feminism, or else show other heroes why that’s a false choice.

Even the most conventional superhero dust-ups say something about society: that it’s worth saving, for instance, or that unusually powerful entities are sometimes required to save it. And Busiek (who calls himself a “woolly-headed Massachusetts liberal”) says a lot more in his stories: about the limits of institutional power, about separatism and solidarity, about the mixed blessing that is law enforcement. The self-aggrandizing crime fighter Crackerjack ties up miscreants and presents them to cops: “I don’t suppose you’ve got any evidence,” one officer asks, that “they were actually doing something criminal?” Other storylines implicate corrupt, or thoroughly compromised, police; the longest one so far, The Dark Age (in two volumes) follows a troubled black cop and his impulsive criminal brother as they track down the henchman who killed their dad when they were kids. Most of The Dark Age takes place in the Reagan years, when movies, politicians, and many comics celebrated a selfish, callous, stubborn vigilantism that is exactly not, in Busiek’s view, what superheroes should be.

Image courtesy of DC Comics.

You can see superheroes as loose cannons or fascist tools, but you can also see them as community superactivists, leading by example, backing unpopular causes, and improving the civic order by doing what government can’t or won’t. (You cannot, however, see them as revolutionaries; that would make them supervillains.) And you can’t read a lot of Astro City without picking up on those cautiously hopeful views.

You can, however, read it for other reasons, not least for its powers of invention. My very favorite Busiek-Anderson creation is Beautie, a flying android who looks like a lifesize Barbie, loves clothes, has no intuition about human sex, and prefers to hang out in gay bars (you can find her origin in Shining Stars). There’s also Mirage, a blaze of glowing vectors who looks like he came from the movie Tron; Atomicus, whose melancholy story we get through the eyes of his former girlfriend; and the grimly noble, determinedly allegorical Silver Agent, who is always traveling back in time to the moment of his own wrongful execution, in 1973. Present-day Astro City has a statue of the Silver Agent, in Memorial Park, inscribed “To Our Eternal Shame.”

Photo illustration by Slate. Covers courtesy Image Comics, Homage Comics, and Vertigo Comics.

“Everything we do is unrealistic,” Samaritan says, and in conversation, Busiek rejected the label of realism. Yet his stories show the kind of faith in character—created and constrained by social systems, unfolding in dialogue, revealed in small choices—that you can find in Victorian novels. Astro City is not Middlemarch, but you can set its best parts next to Adam Bede, or next to O Pioneers!, or A Visit From the Goon Squad, or television’s Friday Night Lights, which might be the best noncomics comparison (substitute battles for football games). Busiek doesn’t have actors to speak his lines; on the other hand, Connie Britton and Kyle Chandler didn’t have Anderson and company’s splash pages, panel borders, or word balloons. Nor do they have the fan-favorite, soft-focus realism of Alex Ross, who creates the covers for every issue.

Astro City is not without precedent. Earlier comics (such as Chris Claremont’s New Mutants) had shown superbeings at home and at play. Busiek and Ross’ own 1994 hit Marvels retold Marvel Universe history from a newspaper photographer’s point of view. “Writing Marvels proved to me that I could do it,” Busiek recalled, “and gave me the stature in the industry.” But Astro City was what he always wanted: “I’d think about comics while walking to school and wonder what it would be like to see Iron Man rocketing down the main street of my hometown, rattling the store windows,” he said. “Or seeing the posters on my sisters’ walls and thinking about who teen girls in the Marvel Universe would have on their bedroom walls.”

What’s special about Astro City is not just the frequent focus on non-superpeople, but the detail, the consistency, and the patience that its quiet stories require. An Astro City plotline almost never has its climax in a fight; stories can turn sentimental, but they never feel compromised or look rushed. A finicky reader might object to its nostalgia, but you might as well object to rock songs using guitars. Its characters and storylines are not darker or more sophisticated answers to the worlds in earlier superhero comics so much as they are those worlds’ own best selves; they are what readers who loved superhero comics—and complained about them, and wanted to live for a while inside their worlds—have wished that those comics could be.

—

Astro City by Kurt Busiek, Brent Anderson, and Alex Ross. Ongoing series. Vertigo.

Volume 1: Life in the Big City. Vertigo.

Volume 2: Confession. Wildstorm.

Volume 3: Family Album. Wildstorm.

Volume 4: The Tarnished Angel. Wildstorm.

Volume 5: Local Heroes. Wildstorm.

Volume 6: The Dark Age Book One: Brothers and Other Strangers. Wildstorm.

Volume 7: The Dark Age Book Two: Brothers in Arms. Vertigo.

Volume 8: Shining Stars. Vertigo.

Volume 9: Through Open Doors. Vertigo.

Volume 10: Victory. Vertigo.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.