One day about three years after I’d left the New Yorker to become a book editor, Alberto Vitale—former CEO of Random House, Inc., a genial, intelligent, and remarkably tan businessman, originally from Italy and Olivetti—stopped me in the hall outside my office. “Profesore, how are you?” Alberto said. Fine, I said. “Good,” he said. “I think you are doing well here,” he went on in his Chico Marxist accent, “but don’t forget that we always have to move the units.” Yes, I said. “The main thing is to sell the books,” he said. He clapped me on the shoulder and went on his beaming way.

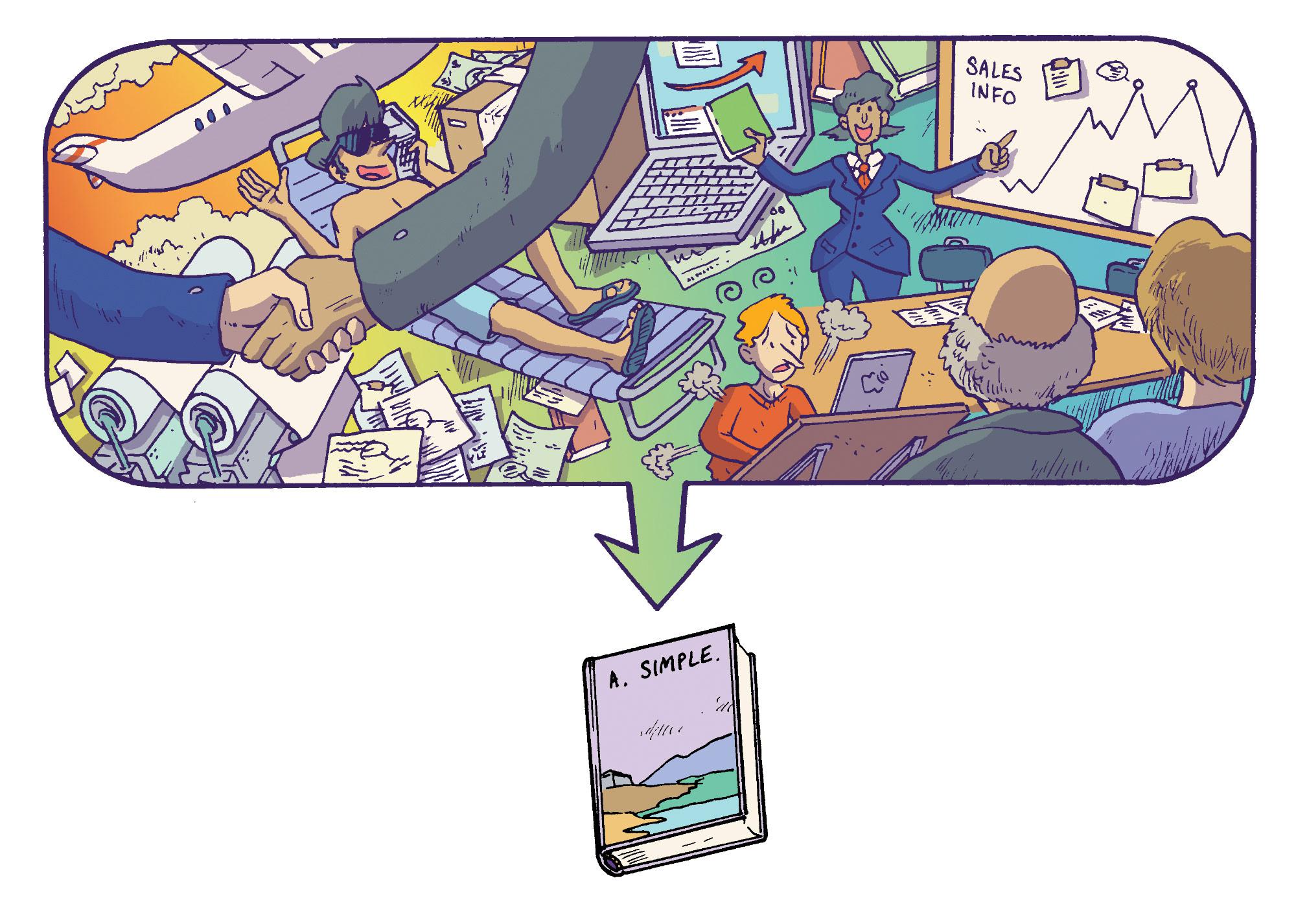

Even as a literary editor and writer, cossetted for many years by the New Yorker’s advertising revenues, I had of course known abstractly about the bedrock publishing necessity to sell physical objects—move units—and make money. But early on, this necessity nevertheless came as a shock to me. And it continued to discomfit me, at least mildly, for all 15 years I was at Random House, almost five of them as editor-in-chief. My family background and education had been at least non- and in many respects anti-corporate. I often forgot to take my business card with me to lunch. It seemed silly. I couldn’t quite get above my raising. (Below it, is what I really think.)

Now, seven years after having left Random House, in the face of the rise of digital texts and Amazon’s Grendelian presence in book sales, the issue of moving units vs. literary culture in publishing has taken on a more urgent and more public and seemingly more complex immediacy. A long confrontation between Hachette publishers and Amazon has ended, but not before a huge group of writers banded together to form Authors United, which sided with Hachette and took strong exception to the retailer’s policies and conduct. And not before another significant, opposing, mainly online cohort excoriated publishers and writers for their (our) complaints. A sample posting: “The Authors United impact was, predictably, zilch. Is it really a revelation that Amazon, like any other business, sees the commodities it sells as … uh … commodities? The publishing and bookselling businesses are just that – businesses.”

The issues here are indeed, at least superficially, more complicated than they used to be, even just seven or eight years ago. E-book pricing, the agency model, author royalties from electronic sales, publishers’ cuts from those same sales, self-publishing, and down-sizing—they have all left many people who care about reading and writing, including editors and writers themselves, at sea about the financial and cultural future of book-length texts.* Any-length texts, actually.

But at the heart of these matters there is nothing new. The push-me pull-you tension between creativity and money is ancient. The one generally, and often uncomprehendingly, envies the other, wants what the other has, wants to materially or aesthetically gain from the other. That has to be the only reason that Amazon started its own—and continuingly vexed—publishing program. And why it wants to have a say in curating literary culture, under the leadership of Sara Nelson, the respected former editor-in-chief of Publisher’s Weekly.

These moves are at odds with Amazon’s objective to “disintermediate” the connection between writers and readers. Right now, the principal intermediaries between writers and readers continue to be publishing companies, large and small. They make their choices, pay more or less for them (usually less), more or less support them (usually less), hope that they have good bets and good luck in the casino that is publishing. In my judgment, there are between 20 and 30 editors and publishers in New York who—along with experienced and discriminating publicists, marketers, and sales reps—have over the decades regularly and successfully combined art and commerce and, in the process, have supported and promulgated art. They are in fact the main curators of our life of letters. They have somehow survived the grinding—tectonic—friction between creativity and business and made a go of both. They are cultural heroes, actually.

As an analysand and an armchair analyst, I can’t help suspecting that whether they consciously know it or not, people like Jeff Bezos and the New Republic’s Chris Hughes want some of that. Well, they can’t have it. Like patrons of old and some of new, they can stand back and support it, sponsor it, admire it. They can give it parties at retreats in New Mexico. They can even sort of own it. But they can’t have it. Because they need to make a lot of money. And because they don’t have the background, wide experience, native zeal, eye for talent, editorial skill, intuition, and intermittent disregard for probable profit necessary to perform the role of literary concierge.

(More darkly and Freudianly still, since they can’t have it, maybe they want to kill it.)

The modern, often online and anonymous, neo-Levellers who object to the “elitism” of publishing arrive at their position from the other side, the populist. They are often writers who have failed to get published by mainstream publishers, even good independent presses. Or readers who decry “snobby,” difficult books. One of the loudest voices in this group denunciation belongs to Barry Eisler, a self-published author who told the Guardian that the signatories of the Authors United letter to Amazon were in “the top 1 percent” who “have no interest at all in improving publishing for everyone. Only in preserving it for themselves.”

This is simply not true. Publishers are of course always looking for something new, different, better. Like the record producers of the ’50s and ’60s—Ahmet Ertegun, John Hammond, Jerry Wexler—they want nothing more than to find the next extremely important or highly profitable artist. If they’re one and the same, even better. Someone new, without the disappointing sales baggage that most authors have to lug around. The one in a hundred or more likely thousand who will go on to have a long and important run as a writer of books. Elmore, Zadie, Alice, J. M.

It’s a rum game altogether, usually—just barely a profession. It involves endless chicken-salad-and-Diet-Coke lunches that end with almost-sure-to-go-unread books being exchanged, email after email studded with forlornly cheerful exclamation marks, years between signed contracts and on-sale dates, almost funereal editorial and marketing meetings, book fairs held in hangars filled with unbounded enthusiasm almost indistinguishable from desperation—and then, for example, the random disaster of a good, funny novel about divorce being assigned for review in a major newspaper to someone who has just undergone a bitter same.

But it is a profession, as well as a business. No matter what its new configurations turn out to be, it will need professionals to guide it. Even if all the professionals and connoisseurs and curators are temporarily leveled into the ground by geeks wielding pixels, new ones—new, techno-adept experts, people who know what they’re talking about, culturally speaking, will spring up from the seemingly undifferentiated digital soil like Cadmus’ army sprung from dragons’ teeth. Or old ones will adapt. (For an almost impossibly erudite and complex elaboration on this point see Leon Wieseltier’s piece in the New York Times Book Review.)

The profession, in whatever form, will continue to produce physical and now electronic objects that move not only units but people. Move them and enlighten them emotionally, move them to action, move them to share what they learn and care about with others. It’s not incumbent on those who defend the publishing industry/business/art and book reviewers to justify the gatekeeping services they perform, however imperfectly. It’s incumbent on those who want to fire the gatekeepers and tear down the very gates themselves to explain what, if anything, will replace them.

*We needn’t worry—such works, by talented people, will always be in demand. Even if and when we can slide a book chip into a portal in our skulls which is connected to our brains and instantly grok the text in its entirety, chips with better stories, of whatever fictional or nonfictional kinds, will sell better than chips with inferior ones. (Return.)

—

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.