Reading a book about tragedy is not itself a moral act. Many books are written as if feeling a lot of sympathy is enough to keep the reader on the right side of history, but Marlon James doesn’t play that game. His second novel The Book of Night Women—the fourth book of five we’re naming this week to We Second That: The Slate/Whiting Second Novel List—is not a redemption narrative. Redemption is tough to find on a plantation in Jamaica in 1801. As the main character, strong-willed teenage slave Lilith, learns from killing, “blood don’t taste like wine”—and as long as there is slavery there will be blood. Page after page, in small ways and large, James made me realize how rote and well-established my emotional responses are.

Lilith’s father is the overseer. After killing a man who tries to rape her, Lilith is taken under cover of darkness into the kitchen of the big house, sheltered by Homer, the head of the relatively privileged house slaves. Like many teenagers, Lilith lives essentially for herself, but in a culture of terror this has a harder edge. She hopes her white master will notice her beauty and raise her up above the other slaves, but when faced with abuse, she has something in her that can’t help but fight, that can’t bend too low. Lilith thinks often about the light in her and the darkness, of how she contains both, just as she contains white and black blood. Homer sees this fire in her and believes that she will help with the uprising the night women are planning, inspired by the successful Saint-Domingue rebellion led by Toussaint Louverture.

A big, masterful novel like this raises questions without answering them—it raises questions that stay raised. Reading this book, I was ashamed at the relative paucity of my historical curiosity and imagination. I once argued with my husband that we should name our son Toussaint, for example, but James’ unflinching engagement with history made me realize that I have read books on how Nazis, fascists, and communists found willing executioners, but never one on the psychology of the overseers of 400 years of slavery. This epic, beautiful, complicated, enthralling book, filled with damaged people living in the misery of a plantation, where “white man sleep with one eye open, but black man can never sleep,” raises an obvious question: Who the hell were these white people? They weren’t aberrant sadists—they constituted basically the entire white population of their communities. It’s horrible to ask this question because the odds overwhelmingly suggest that if any of us, regardless of race, had been raised by slaveholders, we would probably be able sit on our porches watching whippings and hangings while drinking lemonade.

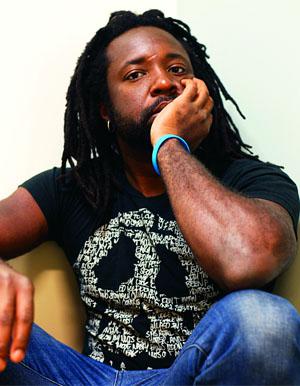

Photo by Jeffrey Skemp

James inspires courage of imagination, he has traversed light and darkness, he has traversed centuries, and he has traversed gender. As the title suggests, this is a book about women, each with her own path through enslavement and her own injuries. Of the six women who plan the uprising, one has been shot blind in one eye, one had her throat slit as a child and has lived as a mute, one is scarred top to toe from the deliberate sprinkling of hot coals by an overseer. Their leader has a “quilt” of scar tissue on her back from whippings and breasts branded to mangled nubs. These women hide their scars beneath scarves and bonnets and clothes. These women have been maimed, inside and out, and so this is also a book about how the indomitable human impulses toward kindness, love, friendship, family, and loyalty are warped so absolutely in a slave’s life as to make a mockery of them. It is also, surprisingly, a heartbreaking love story, of a man and woman haltingly trying, and mostly failing, to overcome their status of slave and master.

This is a vast, deep book. Many chapters begin with the same two sentences: “Every negro walk in a circle. Take that and make of it what you will.” In trying to tell why this book should be read, I feel like I could walk in circles, to the well and back, and always my bucket would come up with a new reason. Take this book, and make of it what you will.

—

The Book of Night Women by Marlon James. Riverhead.

Previous Slate/Whiting Second Novel List picks:

Dan Kois on Helen DeWitt’s Lightning Rods.

Sasha Weiss on Eileen Myles’ Inferno.

Yiyun Li on Daniel Alarcón’s At Night We Walk in Circles.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.