Donald Heiney, who published 16 novels under the pen name MacDonald Harris, turned 2 years old in 1923, the year Safety Last! came out, and entered into film history the image of Harold Lloyd dangling from the arms of a clock, high over Los Angeles. Heiney’s earliest memories of Saturdays spent at a movie theater in South Pasadena, where he grew up, involve that image, which frightened him. He was too young for Lloyd, whose antics, the author remembered in a memoir of his early years, once caused the wee Heiney to gasp in fear. His mother, sympathetic, tried to assure him: “It isn’t real.”

The cinephile protagonist of Screenplay, first published in 1982, develops real trouble with his sense of what is and isn’t real, and the novel, newly reissued by Overlook Press, teases out a malaise that movie going is shown to both soothe and exacerbate. Alys, the heir to a flush-toilet fortune, orphaned at a young age by his glamorous but rather useless parents, lives a detached and self-loving life in Los Angeles circa 1980. His main appreciations are for baroque music, movies from the 1920s, and his own handsome image, reflected back at him from the mirrors covering his bedroom walls and ceiling during masturbation.

When this full life is interrupted by the arrival on Alys’ doorstep of an old, rabbit-y man named Nesselrode, who offers the young man a career in the pictures, Screenplay delves into allegory, and an homage to Alice in Wonderland. Rather than a looking glass, Nesselrode takes Alys through the screen still hanging in an abandoned movie theater. On the other side they emerge into a Los Angeles of the 1920s, where Alys is immediately cast in a series of “fall down parts” opposite an actress named Moira, who bears a strong resemblance to his mother and is naturally his feminine ideal made something just short of flesh.

Alys’ passage into a world “freed … from the limitations of the ordinary human condition,” where “there was no real suffering … no boredom, and no mortality” enacts a familiar fantasy of the movies. The “addiction” to cinema Alys describes is one Walker Percy defined in his classic 1961 novel The Moviegoer, in which another 30-ish, male protagonist discovers in the movies a world preferable to—and more real than—his own. In her recent Lila, Marilynne Robinson’s title character finds relief at the Cineplex, where for a recuperative period she hides from her own life. More so than moviegoing, movie legend has inspired speculative fictions, including Joyce Carol Oates’ Blonde, a gloss on the life of Marilyn Monroe, and Jess Walters’ more recent Beautiful Ruins, which reimagines for one of its storylines the disastrous shooting of Elizabeth Taylor’s Cleopatra. Screenplay mixes the possibilities of both types of novels—involving a shared cultural past and a more personal pastime—to instructive effect: Every fantasy has its price. In the role of performer, Alys is no less passive than he had been as a viewer; he enters an automatonic state, subject to the rules of the silent-film world and the whims of a riding breech–clad director.

If this alternate world exists in shades of black and white, Alys is struck by its familiarity, and a sense of superiority over his previous reality:

The downtown district was exactly as I had always known it, except that now it was new and it was the center of the city. There were no bums or street evangelists; the sidewalks were thronged with well-dressed shoppers and businessmen in black suits and hats. There was Clifton’s, there was Bullock’s, there was the Security Bank building where a well-known goggled comedian had clung by his fingertips to a clock hand seven stories above the street. The yellowish haze of the city was gone. The air was clear and sparkling, with only a slight smell of ozone from the streetcars.

When Alys returns to it, 1980s L.A. appears vulgar and false by comparison:

Bright reds, blues, greens, violets, and yellows glared in the sunshine. It didn’t seem real; it gave the impression of a world brightened with cheap chemical dyes, or a television screen with the color intensity turned up too high. The atmosphere too contributed to the effect of strangeness; there was a thin saffron-colored haze over the street and the air had a sweetish molasses taste in the mouth.

Alys’ further complaints about the present suggest an existential smog. He is a creature of ego and light amusement, unable to desire his clearly desirous female friend, a radio DJ, because “I felt myself incapable of going to bed with a person who knew more about music than I did.” For Alys, “the real world, so called … had always seemed so evanescent and ephemeral that I was never quite sure whether its objects were going to be there when I reached out to touch them.” The world of silent films, at least, makes the exaggerated terms of its unreality quite clear: No one speaks, for one thing, not audibly, anyway, and its inhabitants enjoy immunity from physical law. “Even the laws of psychology and character were different, where there was a freedom, an invulnerability, a kind of zany marionette behavior that made everything simpler and less complex.”

Alys is not a particularly involving character, and Screenplay, despite its flights of cinematic fantasy, is a strangely inert book. The shape of Alys’ experience behind the silver screen and the novel’s resulting insights share a baggy, unresolved quality. Harris’ descriptions, especially of the three films that comprise Alys’ brief career, are extremely close but flatly written—reminiscent, in fact, of a screenplay. The page, for instance, that it takes for two characters to meet, enter a restaurant, and take a seat, begins this way: “I crossed Wilshire on the traffic light, went two blocks down to Cañon, and up the street toward the restaurant. It was only about half a block. When I was perhaps three doors from the restaurant I became aware that someone on the opposite side of the street had stepped out onto the pavement and was crossing it diagonally toward me.” And so on. Intricate sight gag descriptions made me wish I could just watch a character brained by a wooden plank, rather than read an entire paragraph about it. A filmic treatment might also ease the threadbare quality of the novel’s themes—time and the nature of reality, art as a portal to both immortality and the past—and add a badly needed sense of dramatic logic.

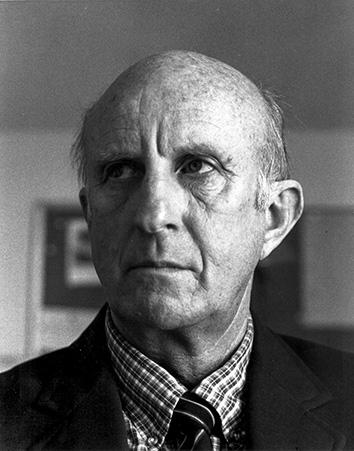

Photo by Ray Orphis

In the afterword to this new edition, British actor Simon Callow describes his pursuit of such a film, over several decades and beyond Heiney’s death in 1993. First money issues and then Hollywood indifference—don’t we already have The Purple Rose of Cairo?— hindered the project. Callow’s dream may yet come true: We now also have Midnight in Paris, after all, and the success of The Artist. More importantly, Harris’ work is in the midst of a revival. His 17th and final novel, The Carp Castle, was published for the first time in 2012; Screenplay is the second of four currently planned reissues. The Balloonist, perhaps Harris’ most celebrated work and a finalist for the 1977 National Book Award, received a new U.S. edition in 2012, with an admiring foreword by Philip Pullman.

I would watch Screenplay, the movie, if only for a glimpse of Moira, the book’s benighted dream girl. In the novel, our sense of her is limited to the extent to which she causes the hero’s atrophied loins to twitch. The picture of gauzy, recessive allure, she is small, amused, perfectly sculpted, her expressions repeatedly described as “slight” or “faint.” As in a silent film, a kiss is all Alys gets before everything fades to black. In a frenzy to consummate, he drags Moira, ideal even in her submission, back through the screen, into the present, where “in spite of the smallness of her body, of everything about her, I had no difficulty in carrying out my wishes with her.” What happens next, the novel frames as Alys’ redemption. Somehow, I suspect that on screen, where she could assume and perhaps even live within some more human form, the same ending would play as Moira’s well-earned revenge.

—

Screenplay, by MacDonald Harris. The Overlook Press.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.