What does a coffee can, a horseshoe, or a stopwatch have to do with a second novel? We asked each of the five authors named to the Slate/Whiting Second Novel List to bring an object to our celebration earlier this month that symbolized the course of writing the book. Read their responses below.

Beowulf Sheehan for the Whiting Foundation

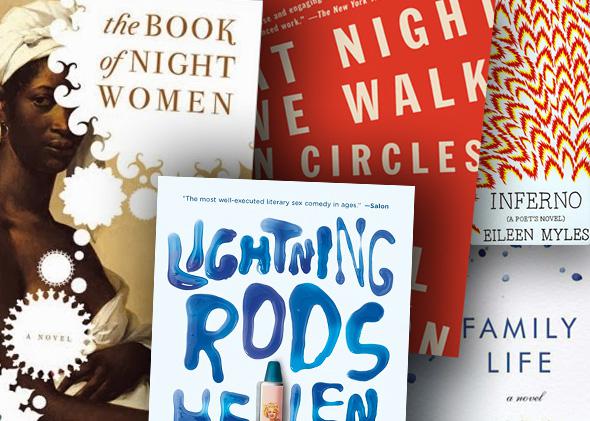

Stopwatch

By Akhil Sharma

I spent 12 ½ years writing Family Life and wrote about 7,000 pages. I wore through two chairs and two computers. If you write for two or three years and don’t make much progress, you begin to think that there is something wrong with you. After four, five, six years, you are convinced that you are a no-talent idiot. My wife was supporting us as I wrote, and I used to feel ashamed all the time. The reason why this semi-autobiographical novel took so long was largely due to technical problems that were hard to solve. The book has a very slight plot and yet to write something that read compulsively, I had to find a language that felt visceral but did not slow the reader down. At some point, I began using this stopwatch. My goal was to sit at my desk for five hours, and either do nothing or write. If a phone call came, I would stop the stopwatch. If I checked my email, I would stop the stopwatch. The watch provided me comfort in that I could say at the end of every day that though I might have no talent, and I might have made a terrible mistake by starting the novel, at least I was showing up every single day to make the book work.

Beowulf Sheehan for the Whiting Foundation

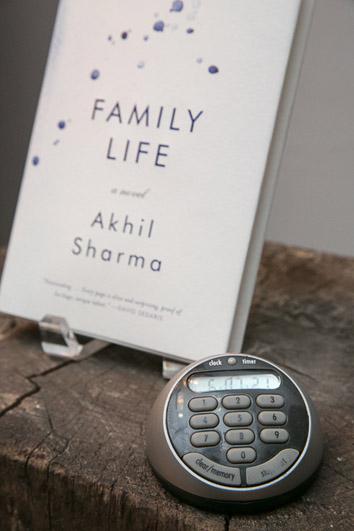

The John Foster Dulles Book of Humor

By Helen DeWitt

Lightning Rods was inspired by The Producers. Mel Brooks had a genius for innocent bad taste, and, as so often, the genius is in the details. My book had a premise in the worst possible taste, but this, I saw, was not enough: It should be crammed with gratuitous jokes.

My luckless salesman went to Kansas City. Bo-ring. But wait! Wait! What if there’s a dwarf in line for the shuttle? Reading the John Foster Dulles Book of Humor?

Fat Guy: To tell you the truth, John Foster Dulles is not someone I would have tended to associate with humor. Or anything else, come to think of it.

Dwarf: People tend not to know a lot about him. The fact is that he was quite an interesting guy, it’s just that Ike hogged the limelight.

“Ike?”

“Eisenhower?”

“Oh, right, right. Right. You know, history was never my strong point, but for some reason I always thought Eisenhower’s first name was Dwight. Am I getting him mixed up with someone else?”

“Ike was a nickname,” said the dwarf.

“Oh. I see.”

“As in ‘I like Ike.’ It was his slogan when he ran for president.”

“You don’t say. Now I never knew that.”

“Where you from, anyway?” he asked, which was exactly what Joe had been thinking.

We’re in business! The JFDBOH deserves pride of place: it showed just how many silly jokes could be spun off a single unsuspecting object.

Beowulf Sheehan for the Whiting Foundation

Can of Café Bustelo

By Eileen Myles

This object most signifies my writing of Inferno, my writing period, and my living in order to write this book and books. Right now a can of Café Bustelo is about a foot from my fingers but it holds scissors and pens and pencils and a pencil sharpener and I can’t risk the loss of this can between now and January. But this coffee is the brand I was introduced to when I moved to New York in the 1970s and it was explained to me as a Puerto Rican coffee and the official New York coffee of the time and it was strong and extremely cheap. This brand was the end of Maxwell House for me and the end of America in a way because I began living someplace where we drank the strongest cheapest possible coffee there is and was and it allowed me to write. And hold pens.

Beowulf Sheehan for the Whiting Foundation

Horseshoe

By Daniel Alarcón

Of the seven-year process of writing At Night We Walk in Circles, the most that can be said is that I didn’t give up. I could have. I wanted to. More than that: At times quitting felt like the only logical thing to do—but I didn’t. From the middle of 2010 until well into the next year, everything seemed hopeless, and I felt like a fraud. It was a weight, a kind of despair I carried with me every single day. Every morning I had to fight with myself just to sit at my desk. Nothing could have felt less important, less relevant, less useful, less joyful than writing. One day, I told my friend Josh Begley that I was ready to quit, that my work was harder and harder to justify to myself. Who cared about novels anyway? I felt like a blacksmith, I said, living and working at the dawn of the automobile age, who’d wagered his and his family’s future on making horseshoes. Do you admire that blacksmith’s commitment to the traditional form, or do you shake your head at his lack of vision

A few days later, I got a box in the mail. When I opened it, I found a horseshoe. There was no note, but the message was simple enough to read: Don’t give up.

I keep this horseshoe on my desk at all times.

Beowulf Sheehan for the Whiting Foundation

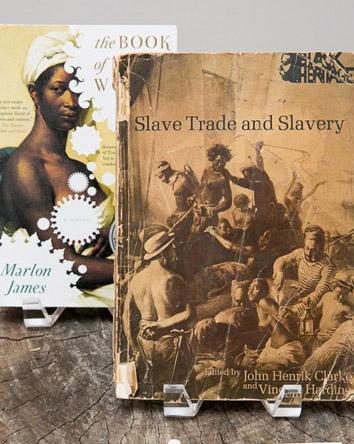

Slave Trade and Slavery (Black Heritage Series)

By Marlon James

I have never read this book. January 2012, my father had just died, and I was cleaning out his desk. Beneath Kahlil Gibran and Coleridge was this, a book I had not seen since the mid ’80s. The cover stunned me just as hard as it did when I was four. I was horrified by it—at the white men who looked like the people on TV, brutalizing people who looked like me. Whips, branding, sailors looking on as if it was just another job, another day, with a black woman in front, forced to sit still while a man branded iron into her flesh. Usually when a child stumbles across a book meant for adults, it has something to do with sex. This was violence—people committing atrocities on other people, and I didn’t understand it at all. I was too young to understand the words so I scanned for photos. In a strange way, I also scanned to find my father, who was unreadable to me. I traced every line he underlined in red that I couldn’t read; I ran my fingers over his handwriting in the margins (also in red), as if what prompted him to write was a mystery to solve. As a writer I still think that’s why I do what I do: There’s a mystery to solve. Reading my father’s underlined passages now, I am moved mostly because he was moved. And in returning to the cover that I had not seen in decades, the genesis of The Book of Night Women finally made sense to me. “What inspired you?” is a tired question. But there was the answer staring at me with her dismayed eyes, exposed breasts, bound hands and branded back. She was a mystery I was trying to solve.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.