There is a word in Russian, byt. Roughly translated, it means everyday life. It is also the root of the infinitive verb byt’, “to be,” as though the Russian language itself believes that it is the day to day—waking up, going to work, trying to earn enough to eat, wanting very badly to love and be loved in return—that makes up who we are. Everyday life is the root of being, according to Russian etymology—and to Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, the dazzlingly talented and deeply empathetic author of a new collection of three novellas, There Once Lived a Mother Who Loved Her Children, Until They Moved Back In.

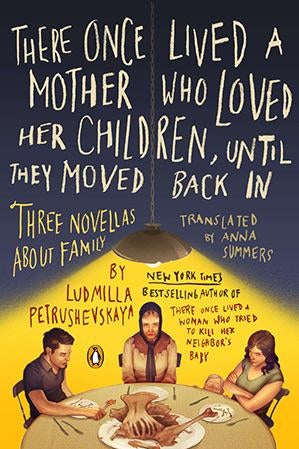

Born in Moscow in 1938, Petrushevskaya has alternately been proclaimed the greatest living Russian writer and the last of the great Russian writers. (Penguin has been translating and collecting her stories in charming paperbacks with long titles: There Once Lived a Girl Who Seduced Her Sister’s Husband, and He Hanged Himself, There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby.) Some fans might have been dismayed when she took up cabaret singing a few years ago, but having a second career is a very “great-Russian-writer” thing to do: Chekhov was a doctor, Dostoevsky was an engineer, Bulgakov was a doctor, and Tolstoy had that whole second stint as a wannabe peasant.* And, indeed, in the novellas in this collection (translated by Anna Summers), Petrushevskaya consciously inserts herself into the tradition of great Russian literature.

The first tale, “The Time Is Night,” originally published in 1992, is the story of Anna, a grandmother struggling to take care of her grandson while fending off her predatory grown children. The story does not begin with narration. Rather, it is introduced as writings contained in a folder Anna has left behind—a framing device used by all of the aforementioned greats, including Dostoevsky, who gets a nod in the folder’s label: “Notes from the Edge of the Table.”

The second novella, “Chocolates With Liqueur,” published in 2002, offers a Russian twist on Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado.” But Petrushevskaya infuses her “Chocolates,” about a woman seduced into a dangerous situation by her love of sweet wine, with the Russian literary tradition: The story is told out of chronological order, a technique used so often in Russian writing that there are terms—fabula and syuzhet—that distinguish between the story’s chronology and the sequence in which the events are told.

The last of the trio, 1988’s “Among Friends,” in which a woman goes to extreme lengths to ensure that her son is taken care of by her social circle after she dies, is a satire of the secret salons of the Russian intelligentsia in the late Soviet period. It targets the scientists and writers who cowered inside their communal apartments, fancying themselves intellectual crusaders but unable to be morally decent to each other in their everyday lives. “Kolya, so generous and kind to others, quickly gets bored and irritable at home and yells at Alesha, especially at mealtimes,” reveals the narrator. “In addition, Kolya was preparing to leave us, and not just for anyone—for Marisha.”

But in these stories, Petrushevskaya is not only establishing her place in the Russian literary tradition. She also changes it, and what are considered acceptable literary topics therein. She is not, like Tolstoy, writing of war, or, like Dostoevsky, writing of criminals on the street, or, like poet Anna Akhmatova or novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, noting the extreme suffering of those sent to the camps.

Rather, she is bearing witness to the fight to survive the everyday. The skirmishes with family and friends. The too-small, too-shared apartments. (“Andrey was coming home—where would he sleep? What would he eat? How would we manage? I couldn’t sleep and woke up in a cold sweat.”) The food scarcity. (“She and the children had nothing to live on,” we learn of the protagonist of “Chocolates With Liqueur.”)

In “The Time Is Night,” Anna, a poet, refers throughout to her namesake. Though she never specifies, that namesake is Anna Akhmatova, who composed, among other writings, “Requiem,” a lyric memorial to her son in the labor camps. In “Requiem,” Akhmatova writes of those who were sent to the camps, and those who stayed behind, waiting for them: “I’d like to name them all by name, but the list/Has been removed and there is nowhere else to look./So,/ I have woven you this wide shroud out of the humble/ words/ I overheard you use.”

The echo of those lines can be heard in “Among Friends,” as Petrushevskaya’s narrator describes a party: “Ruined pies, cigarette butts, unfinished salads, apple bottles under the couch, Nadya weeping and holding her eye, and Andrey dancing with Marisha in his arms, his annual sacred ritual.” These small details are Petrushevskaya’s version of the words Akhmatova heard while waiting for her son. She has woven them—and those who lived them, who shared the apartments and the food and the unbearable, average, everyday grief—into a wide shroud of humble language. Petrushevskaya, unlike Akhmatova, is not writing of what it meant to suffer and survive through Stalinist purges or labor camps. Her theme is what it means to suffer and survive through lives in kitchens and drawing rooms, schoolyards and government offices. Here, she writes between the lines on every page. Here you are, sad by your sink. Here you are, wretched in your day to day. Here you are, unseen and unheard, until now, by me.

In each of the three novellas, there is a point at which the hero of the story finds relief in the fact that, even surrounded by dirty plates and pots and pans and men who do not provide enough and friends who are not good enough—even so, at least there is life. At the end of “The Time Is Night,” even as she despairs that her grandchildren have been taken from her by their mother, Anna tells us, “The main thing is they are alive.”

The main thing is that they—that we—are alive. Being. With all of the byt that implies.

—

There Once Lived a Mother Who Loved Her Children, Until They Moved Back In by Ludmilla Petrushevskaya. Translated by Anna Summers. Penguin.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.

Correction, Sept. 23, 2019: This article originally misstated that Mikhail Bulgakov was an engineer. He was a medical doctor.