My romance with Chicken Soup for the Soul began and ended with the adolescent iteration, Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul, and it was fostered in part because I read it when I was not yet teenaged. There was so much in that book for a 10-year-old to love: the amazing celebrity contributors (Jennifer Love Hewitt!), the interspersed cartoons, the bounty and variety of quotes, poems, and short stories. The collection was an emotional feast, with courses titled “Please Listen”—“When I ask you to listen to me/ and you begin to tell me why/ I shouldn’t feel that way,/ you are trampling on my feelings”—and “She Told Me It Was OK to Cry.” (@SavedYouAClick for all Chicken Soup books: It is always OK to cry.) I remember, at night, wanting to stop reading but not quite being able to—the anthology became a proto-Netflix binge-read, one chapter gliding seamlessly into the next. Together these maudlin snapshots contained every cliché of adolescence: the all-important school dance, the butterflies around a crush, the sleepovers and hours-long phone calls, the ever-present threat of humiliation (not even a threat, really, but a shimmer of low-level atmospherics, as if embarrassment were the musical key in which your experiences were scored).

I had never encountered stories that explicitly wanted to comfort me before. Here is a typical opening from one of them: “I was 16 years old and a junior in high school, and the worst possible thing that could happen to me did. My parents decided to move our family from our Texas home to Arizona.” How did you beguile, Chicken Soup? Let me count the ways: Accessible first-person narrator, the glamorous phrase “junior in high school,” melodrama (the girl’s life was over), and, more subtly, the manifest not-badness of the upheaval in the grand scheme of things. Every crisis felt so safe and manageable. I loved how I could predict the tale’s ending, with the narrator forging lifelong friendships in Arizona and “meeting the man of my dreams.” Of course, darker forms of adversity arose, too—I closed the book convinced that cancer was the one thing that might go really wrong in people’s lives—but even these shadows had silver linings, moral lessons. (“Will you tell them for me? Will you … tell the whole world for me,” a dying kid asks joyously in one story, having realized that God is love.)

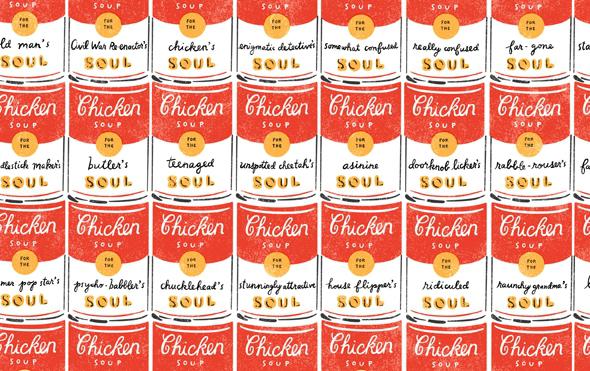

Now, in 2014, Chicken Soup for the Soul is less a series than an empire, a multimillion-dollar franchise with an auxiliary pet-food line. More than 500 million books have been souled—uh, sold—and the original has been translated into 40 languages. The titles pour forth with comic specificity, targeted to every conceivable family member—grandparents, mothers (new and expectant), fathers, sisters, brothers, and various combinations thereof—as well as most major religions (but not, strangely, Muslims, though there is one for Latter-Day Saints). Our soup-craving souls come in vintages mystics never envisioned: Beach Lover, American Idol, Dental, NASCAR, Menopausal, Golfer, Woman Golfer, Canadian, Coffee-Lover, Tea-Lover, Fisherman, Chiropractic, Scrapbooker. A few of the most recent offerings will give you a further sense of the company’s flavor, its recipe for precious, whimsical uplift: They include Chicken Soup for the Soul: Miraculous Messages from Heaven, Chicken Soup for the Soul: Kids in the Kitchen, and Chicken Soup for the Soul: The Cat Did What?

The company has traveled a long way from its humble origins, tracing the kind of underdog, believe-in-your-dreams arc that would work really well in a Chicken Soup book. In 1992, teacher and motivational speaker Jack Canfield hatched a plan to compile all the stories he told on the self-help circuit. He sought narratives that were “inspiring, healing, motivational, and transformational,” that would “open the heart and rekindle the spirit,” and when he shared his notion with his colleague Mark Victor Hansen (“a consummate promoter and salesman,” Canfield writes approvingly in the foreword to the 20th anniversary edition), Hansen wanted in. Hansen suggested that the collection comprise 101 stories, not 70, because “when I was a student ambassador in India, I learned that 101 is the number of completion.” They penned the chapters, found an agent, chose a title (Canfield says the words Chicken Soup appeared to him in a dream in which the hand of God scrawled them across a chalkboard), and flew to New York to meet with publishers.

They struck out. None of the publishers could relate to such “nicey-nice,” “positive” yarns. Without a guarantee that at least 20,000 copies of the book would sell, their agent explained, Chicken Soup for the Soul had little chance of seeing daylight. According to Canfield, he and Hansen began to place “commitment to buy” forms on the chairs at every motivational conference they attended. As the rejection slips stacked up (the authors claim they received nearly 100 from “what seemed like every major publisher in America”), so did the inked promises from audience members. Finally, more than 20,000 promises were enough to persuade Peter Vegso, of the Florida publishing house HCI, to roll out the first Chicken Soup for the Soul in the summer of 1993.

This original serving had an uncomfortably specific flavor. Perhaps because of the New-Agey types telling Canfield and Hansen their stories, characters were often white and rich, their miracles unfurling under well-to-do suburban roofs or in vacation spots in Fiji. The company has since expanded its scope with volumes for the “African American,” “Latino,” and “Indian Teenage” souls, as well as versions for “the working woman,” teachers, and veterans. (There are more than 200 books in the series; about a dozen are released each year.) And as the self-improvement market broadened and flourished into the aughts, Chicken Soup flowed into ever-more-practical niches. Originally an all-purpose mix of entertainment and inspiration, the franchise has reinvented itself in part as a source of celestially-bathed lifehacks, urging readers to “reboot,” “think positive,” and foster their creativity at work.

In 2008, Canfield and Hansen sold the company to a new ownership group led by Bill Rouhana and Bob Jacobs. On the phone, current publisher and editor-in-chief Amy Newmark discussed fresh directions for Chicken Soup for the Soul, emphasizing its inclusivity (“a book for everyone on your gift list”) and deep philanthropic mission. In some ways, that inclusivity is questionable: Chicken Soup still hasn’t released a volume for LGBT readers, for instance, which seems absurd given the range and precision of its demographic targeting. (Chicken Soup for the Soul: Country Music, Chicken Soup for the Soul: Living with Alzheimer’s and Other Dementias.) And the series’ key consumers remain women in their 30s, 40s, and 50s. But Newmark expressed commitment to “reaching everyone” and “making a difference.” She told me the firm hasn’t raised prices on its books since 2003 (“We love our readers and want to give them premium value”), and that it donates much of its revenue to charity, notably the Humpty Dumpty Institute, but also more specific organizations pegged to more specific books, such as the Humane Society for Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover’s Soul. “We’re a socially conscious company and everything we do is designed to share happiness, inspiration, and wellness in an entertaining fashion,” she said. “Our motive is to always give back and do what’s right for people.”

That community impulse extends to Chicken Soup’s submission policy, which has fostered a huge network of amateur authors—“ordinary people telling extraordinary stories,” in Newmark’s words—who can upload their submissions for free. Once selected, a contributor is paid between one and two hundred dollars, and receives an email notice every time a new book theme bubbles up. While submissions have skyrocketed in the age of the Internet (each volume receives about 6,000), the heyday of Chicken Soup sales was the mid-’90s. (“Flat is the new up,” Newmark told me wistfully.) They’ve kept 101 as their magic number on the table of contents, but altered the titles slightly, to give the series more freedom. Chicken Soup for the Fill-in-the-Blank Soul has become Chicken Soup for the Soul: Fill-in-the-Blank. And Newmark admits to a subtle shift in editorial voice. “We used to have flowery language,” she laughed. “But I hired three people with journalism degrees to work here because I prefer that journalistic tone. If someone says, ‘My sadness coursed down my cheeks,’ I’m going to change it to ‘I cried.’ ”

What Newmark doesn’t mention: the diminishing role of the books themselves in the Chicken Soup brand. In 2008, book sales represented 90 percent of the company’s profits; just three years later, that number was 50 percent. Rouhana and Jacobs have leveraged Chicken Soup’s name recognition—one poll found that 87 percent of Americans have heard of the franchise—and its ambience of “hope, faith, and trust” to develop puzzle games, pasta sauce, health and beauty products, and a potential talk show. They’ve insisted that the collections themselves be sold not so much in bookshops as in supermarkets and drugstores. “Don’t look at it as a book,” Rouhana and Jacobs told chain owners, according to an interview with Forbes. Chicken Soup for the Soul is a commodity.

But business story aside, I was most interested in what the anthologies meant to us when they crested the prosperous hills of the Clinton era, and what relevance they might hold today. Despite the growth of the self-help market, has the recession, or irony, destroyed Chicken Soup’s chances of regaining the mainstream? In fact, did we even like them to begin with? Memories were mixed: Slate copy editor Ryan Vogt recalled his sixth grade teacher stopping class occasionally in order to read aloud from the original volume. “I regarded the book as pure cheese at first,” he told me, “but actually got pretty choked up a few times, and came to see the readings as a treat, like Reading Rainbow had been in elementary school.” Writer Mark Stern said he’d borrowed Chicken Soup for the Preteen Soul from his female cousin as a 9-year-old and found it “awful, mawkish, obvious, painful, unbearable, unenjoyable, and scarring.” (How does Newmark feel about Chicken Soup’s reputation for churning out a noxious sludge of sentimental woo-woo? “That’s unfair criticism,” she replied. “I’m not a gooey person and I don’t think that I select that kind of story. I don’t think the previous owners did either.”)

“They were some of the first books that I stayed up late at night reading,” confessed Slate intern Laura Bradley. “I loved them when I was a happy child. By the time I was a tween who wore too much eyeliner—not so much.”

When I cracked the original Chicken Soup for the Soul in 2014 (I had only ever read the teenage version), I was put in mind less of wintertime broth than of some kind of vegan Powerade first introduced to the world via the Goop newsletter. The cynic in me wants to slam the stories as cloying treacle: random acts of kindness preventing suicide in the nick of time; an entire classroom of disadvantaged kids becoming successful doctors, lawyers, and businessmen—every one!—because their teacher loved them. Sentence by sentence, there’s a staggering amount of rekindling, reviving, empowering, dreaming, doing, and visualizing; a profusion of laughter-through-tears; a reliable geyser of gruff fathers finding the courage to tell their sons they care.

I was seduced by my own outrage at the book’s materialism. Along with bliss (unremitting) and serenity (perfect), Canfield and Hansen are big on dizzying wealth and fame. “Imagine how fantastic and successful you’d be if you followed your joy,” one essay smarms. Too often women emerge as accessories or status markers. In “My Soul Mate,” Hansen describes his “twin flame relationship” with his wife, Crystal, and then lists all 112 qualities he looks for in a woman, including “slender and radiantly fit,” “smells good naturally,” “social graces and practices,” and “master kisser/lovingly tactile.” “Chicken Soup is the worst,” I told my roommate, flinging down the book. What I didn’t say was that I’d been reading for an hour and I’d already cried three times.

That is the problem with Chicken Soup for the Soul. It gets to you, even when you know better.

“I knew in my bones that the love we give and receive is all that matters and all that is remembered,” asserts the narrator in one story. “Suffering disappears; love remains.”

Chicken Soup’s creators would claim they want to reflect readers’ lives back at them, but kindly, so that we see the beautiful truth about who we are. To me, the books’ effects are more bound up in escapism and wishful thinking. It’s not just that they transport us to a world of simplified conflicts, fairytale endings, and cathartically dumb psychobabble. To read them is to surrender to that part of the reading self that longs to believe someone is writing with you in mind. You, the Indian teen. You, the fisherman scrapbooker. You, the indescribably specific, individual spirit. When the stories are doing their job, behind them seems to float an intelligence that fervently wants the best for whomever we happen to be. Who cares how silly that intelligence is? Martin Amis doesn’t care if we thrive. Chicken Soup for the Soul just might. And that is at once rare, empowering, and comforting. Inspirational, even.

—

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.