Early in Tana French’s latest mystery The Secret Place, two teenage girls search out a window at the top of a shopping mall and thrill at the view of Dublin beneath them:

And there it was, spread out below them: the magic world they’d been promised, neat and cozy as storybooks. There was washing billowing on lines and little kids playing swing-ball in a garden, there was a green park with the brightest red and yellow flower beds ever; an old man and an old lady had stopped to chat under a curly wrought-iron lamppost, while their perky-eared dogs wound their leads into a knot. … In the end a security guard showed up and threw them out … but it was a million kinds of worth it.

The city seems far away to these girls, whose lives are largely confined to the grounds of St. Kilda’s, a private school in a leafy Dublin suburb. But their longing for what that storybook view represents—home, family, belonging—fuels a dense tangle of friendships and rivalries that the novel’s protagonist, Detective Stephen Moran, has to unravel to solve the mystery of a murdered teen boy.

The Secret Place is the latest installment in French’s Dublin Murder Squad series, a masterful set of five detective novels that constructs a deeply observed portrait of modern Dublin. Seeing a city unfold over time through the eyes of a detective is, of course, one of the great pleasures of crime fiction—think of Los Angeles in Michael Connelly’s Harry Bosch series or Chicago in Sara Paretsky’s V.I. Warshawski series—but French’s series explores Dublin with remarkable scope and dexterity. Each successive novel has centered on a detective introduced in a previous novel. It’s a handy gimmick, sure, but it’s also created a structure that’s allowed French to explore, in increasingly nuanced ways, the city she calls home.

In the first of the series, In the Woods (2007), Detective Rob Ryan investigates a homicide in a suburban Dublin estate where he was the victim of an unsolved crime 20 years prior. In the next book, The Likeness (2008), Cassie Maddox, Rob’s partner on that case, goes undercover to investigate the homicide of a Trinity College grad student who bears an uncanny resemblance to her. In 2010’s Faithful Place Cassie’s boss, Frank Mackey, returns to the eponymous Dublin tenement where he grew up and unearths the murder of the girl he planned to run away with two decades ago. In 2012’s Broken Harbor Mick “Scorcher” Kennedy, who investigated the Faithful Place murder, catches a case involving a young family living in a half-built, nearly abandoned housing development outside the city.

The Secret Place catches up with Stephen Moran, an up-and-comer who went behind Mick’s back to help Frank in Faithful Place, as he works to solve a homicide at the private school Frank’s daughter attends. Because each detective has a different history in the city, each book investigates a set of locations and relationships from his or her point of view; because they all remain connected, each book provides an opportunity to see characters we’ve already met through a different set of eyes. There is no objective vision in French’s novels. Reading them is a singular experience of discovery and rediscovery, and each book evokes the gratifying feeling of gaining unexpected insight into a person or place you thought you knew well.

Like those girls in the shopping center, all of French’s characters are compelled by the idea of home. Rob, Frank, and Mick have to make homecomings, of various sorts, in order to solve their cases. Cassie finds herself unexpectedly drawn into a circle of friends who’ve conspired to create a family for themselves by excising their pasts. And the girls of St. Kilda’s try to negotiate their liminal space by carving out a makeshift home where friends become family. French’s novels are full of Dubliners yearning for places to call their own. Kids take to the woods behind their estates, colonize abandoned row houses, and lay claim to private spaces beyond school walls. Adults are often consumed by finding, buying, and inheriting houses.

This desire for home is inexorably tied, French makes clear, to the history of Ireland. “This country’s passion for property is built into the blood,” Cassie observes in The Likeness, “a current as huge and primal as desire. Centuries of being turned out on the roadside at a landlord’s whim, helpless, teach your bones that everything in life hangs on owning your home.” The legacies of colonialism, battles over Home Rule, and waves of emigration underpin the development of modern Dublin. Tana French explores not just the cost of class mobility, but also what drives it.

The rise and fall of the Celtic Tiger has served as backdrop of all of French’s novels. The childhood homes of the detectives evoke the recession of the 1970s and ’80s. Rob Ryan’s family was among the first Dubliners to move to the suburban estate of Knocknaree, a location that offered families the opportunity to “escape from the tenements and outdoor toilets that went unmentioned in 1970s Ireland” and “buy as close to home as a teacher’s or bus driver’s salary would let them.” The Faithful Place of Frank Mackey’s youth was full of “factory workers, bricklayers, bakers, dole bunnies, and the odd lucky bastard who worked in Guinness’s and got health care and evening classes.”

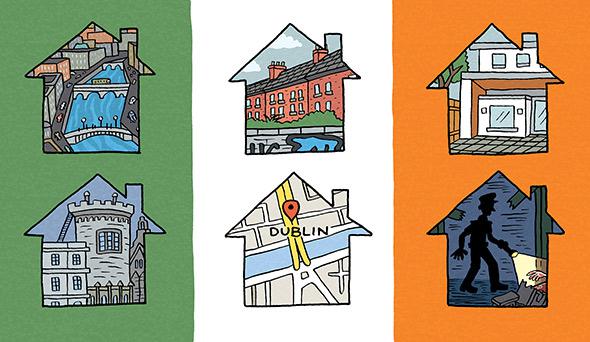

Courtesy of Kyran O’Brien

When Rob returns to Knocknaree, the woods, and the archeological site they cover, are just a month away from being bulldozed to make way for a new motorway. When it comes to real estate, all roads either lead into or out of Dublin. In the first two novels, the property boom is in full swing in “hip, happening, double-espresso Dublin.” By the time Frank returns to his newly gentrifying neighborhood in Faithful Place, development is stalling out, and the boom is starting to look more like a bubble. In Broken Harbor, the bubble has busted. The victims in Broken Harbor are a young family who move an hour’s drive outside of Dublin with the dream of claiming their rightful place on the “property ladder.” They get their house, but their dream becomes a nightmare of isolation after the developers pull out, leaving the few families who live there in an abandoned ruin of half-built streets and houses.

Development is a contentious issue throughout the series, but French avoids moralizing about it. She’s more interested in how development surfaces the past even as it buries it, bringing old history and resentments into the present. In The Likeness, the manor that Cassie Maddox and her companions occupy is the “Big House” from an Anglo-Irish feudal estate. The locals, descendants of the villagers who were brought to the area to work for the estate, are eager to see the house sold to developers to help shore up the local economy. “All these private, parallel dimensions,” Rob Ryan observes about Knocknaree, “underlying such an innocuous estate; all these self-contained worlds layered onto the same space.” He could easily be characterizing many of the places in French’s novels. Even St. Kilda’s, where the sequestered world of teen girls seems far outside history, was “someone’s ancestral home, once.”

And the precipitating event in Faithful Place is development: Construction work on an abandoned row house turns up Rosie Daly’s suitcase and leads Frank Mackey to her body. It’s simply not possible to escape the past in these novels. Frank and Rosie made plans to run away together to England, joining the wave of Irish emigrants of the 1980s. Frank—along with the whole neighborhood of Faithful Place—spent 20 years hoping that Rosie was “the one that got away,” only to find her buried in the place she sought to escape.

But history is a comforting weight as well as an oppressive one. French chooses Dublin Castle as the headquarters for her Dublin Murder Squad. It’s a point of pride among the detectives that they work every day in “eight hundred years’ worth of the buildings that have defended this city, in one way or another.”

It’s perhaps no surprise that there’s a sense of deep nostalgia for preboom days among French’s detectives as they contemplate Ireland’s uncertain future. Despite their trauma-filled childhoods, Frank, Rob, and Mick hold on to the belief that the country was safer when they were kids. “Safe as houses,” is how Frank Mackey describes the 1980s, without any irony, despite the fact that he was anything but safe from violence and abuse in his own home. This nostalgia often carries over into a reverence for an older, more “real” Dublin, the city of bricks and stone that will inevitably outlast the modern glass and steel structures being built over the top of it. When he looks at “shoddy new apartment blocks and the neon signs,” Frank Mackey thinks, “They’re nothing; they’re not real. In a hundred years they’ll be gone, replaced and forgotten. … it’s the old stuff, the stuff that’s endured, that might just keep enduring.”

Tana French’s Dublin is, itself, not quite real: She blends fictional locations with actual ones. In her afterword to Faithful Place, she explains why she chose to resurrect Faithful Place, a neighborhood that no longer exists, and relocate it in the Liberties, still a thriving Dublin neighborhood: “Every corner of Liberties is layered with centuries of its own history,” she writes, “and I didn’t want to belittle any of that by pushing an actual street’s stories and inhabitants aside to make way for my fictional story and characters.” In writing these novels, French is forced to reckon with all the private, parallel dimensions of the city she calls home; she, too, has to negotiate the weight of history.

It’s no small task to write about Dublin. It’s nothing if not a literary city, and reimagining it would be impossible. (As Mark O’Connell astutely noted in his essay on the centenary of Dubliners, “Joyce will not be escaped.”) Yet, with the Dublin Murder Squad series, Tana French has managed create a Dublin that feels thoroughly contemporary. Home is not a fixed point, but a series of interconnected locations. The map she draws with the Dublin Murder Squad series is layered and relational: The street view always depends on who’s looking.

The Secret Place by Tana French. Viking.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.