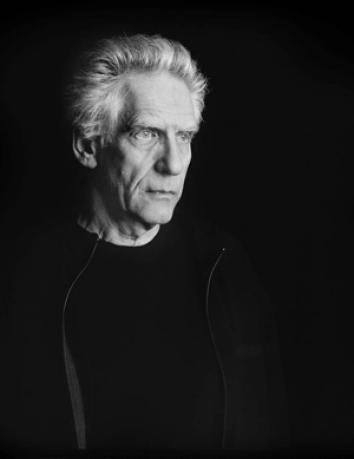

The ur-image of Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg’s work comes from his 1983 film Videodrome, when James Woods, faced with the breathy, cooing commands coming from a video image of Deborah Harry on a tube TV screen that has become a two-way street, allows his entire head to become engulfed by Harry’s analog lips. Cronenberg is often pigeonholed as the great auteur of “body horror,” but he often seems more interested in what you could call “embodiment dysmorphia.” Some of his films explore the horrific possibilities of physical transformation, but just as often, the horror is that the bodies in question are not what their owners want them to be, or all they could be, or what they appear to be. Sometimes, the desire to transcend the dull husk of corporeality dovetails with a seemingly utopian technology that Cronenberg’s characters don’t fully understand, but which is too seductive to be resisted.

Cronenberg has produced a widely varied body of work, but that Videodrome sequence seems to be everything important about Cronenberg’s aesthetic, happening all at once—the possibilities of what we could do with our bodies becoming at once limitless and terrifying, punk glamour and cynical consumerism merging in sex-tech viscera that’s at once explicit and ambiguous. The scene was stuck in my head like a cloying pop hook while reading Cronenberg’s first novel, Consumed, a globe-trotting 21st-century noir, which at first seems to delight in the cool, futurist potential of the present, and then slowly reveals itself to be a cautionary tale. In Cronenberg’s world, it’s a given that illusory interconnections are going to form between the human body and everyday technologies; but because it’s so easy to embrace and come to rely on those technologies without any thought to their philosophical implications or underpinnings, the danger is that, like James Woods in Videodrome, interfacing with a machine could cost you your head.

Consumed begins as the story of a journalist couple, Nathan and Naomi, who travel the world separately with their laptops and high-tech portable camera packages looking for stories. They move quickly, self-styled mercenaries who rarely make time for introspection. It’s a rare moment when these two are not interfacing with another human in person, via technology, or both. Nathan and Naomi are a new spin on the old trope of the lone wolf: They work alone, but no one with an iPhone is ever truly alone.

Naomi works for a Vice-like pub and Nathan is freelance, but both are looking for niches that have not yet been colonized by others, and yet are sexy enough to appeal to the clicking masses. So Nathan goes to Budapest to photograph a shady experimental cancer procedure, hoping it will seem legit enough to get his foot in the door at The New Yorker. Meanwhile Naomi is in Paris, trying to get to the bottom of a scandal involving a couple of celebrity, French philosophers/sexual outlaws Célestine and Aristide Arosteguy. In what the Paris police prefect has called “a national disaster,” Célestine has apparently been murdered, her body mutilated, and parts of her flesh cooked and eaten. Aristide, the prime suspect, was lecturing in Asia when his wife’s body was found and is now considered missing. Eventually Nathan and Naomi’s paths crisscross, and both end up too close for comfort to their subjects. Nathan moves into a basement room in the home of Dr. Barry Roiphe, long famous for lending his name to a venereal disease and now puzzling through the unexplained fugue states of his gorgeous, troubled daughter. Naomi finds herself in Tokyo, in the secret hideout of probable wife murderer/cannibal Aristide.

As a couple, and as journalists, Nathan and Naomi seem to be mostly post-moral: Their work is intentionally exploitative, and they draw little if any line between the professional and personal. Certainly, neither has a compunction about sleeping with a subject, and infidelity as such only becomes an issue when Naomi becomes frustrated that, during the one scene in the novel in which the pair are actually in the same room, Nathan manages to pass her an obscure STD. Cut from the same cloth in some sense, Nathan and Naomi call one another “Than” and “Omi”—as if to embrace the parts of the other that don’t overlap. In fact, this evocative baby talk is the primary continuing indicator that Nathan and Naomi do have a shared history that they care to hold on to. Otherwise, their alienation from one another expands, even as the stories they’re separately tracking start to converge and become open for, as Naomi puts it in what could be a quintessential Cronenberg phrasing, “cross-fertilization.”

With Nathan and Naomi as our questionably reliable narrators and opportunistic sleuths, a global conspiracy unfolds. These nouveau Nancy Drews keep opening doors onto new rooms. Sometimes what they find in those rooms seems to be a red herring while other times it seems almost too neatly connected to what the other is finding fully halfway around the world. Apotemnophilia, or “Apo,” a body dysmorphia that compels its sufferers to seek out unnecessary amputations, connects to experimental hearing aid innovation. Three-dimensional printing is cultishly embraced as the cinéma vérité of the future. A key fulcrum is the discovery that the Arosteguys had published an essay called “The Judicious Destruction of the Insect Religion,” exploring “Weber. Capitalism. Vatican. Luther. Entomology. Sartre. Consumerism. Beckett. North Korea. Apocalypse. Oblivion.”

Each new discovery is a branch off of the main vine of Consumed’s plot; many of these branches require a character of even more uncertain trustworthiness than our (anti)heroes to explain some amount of backstory. Meanwhile, present-day action is often taken up with the act of mediation: Nathan taking or editing photos, Naomi piecing together clues through Google searches and Web videos. At times—particularly during the first 175 pages, which alternate between Naomi’s and Nathan’s storylines—Cronenberg’s prose reads as though he’s transcribing the sound and image of a movie he hasn’t made. The first few pages of the book are a frame-by-frame description of a news clip that Naomi is watching on her computer, narrated by an “overly earnest newscaster”:

The camera zoomed in on the amiably chatting Aristide. “Her husband, the renowned French philosopher and author Aristide Arosteguy, could not be found for questioning.” In one brutal cut Aristide disappeared, to be replaced by handheld, starkly front-lit shots of the tiny apartment’s kitchen, apparently taken at night. These soon swelled to full size and the newscaster’s window retreated to the upper right corner.

Photo by Myrna Suarez

And so on. For a film director to fill the first pages of his first novel with so much descriptive language regarding camera work and editing immediately submerges Consumed into an uneasy middle space between literature and cinema. An impatient reader might start to wonder why Cronenberg, still a very active and internationally well-respected filmmaker at 71, would choose a novel as the format for this particular story, when it seems like what he really wants to do is to make a film. And for a while, the fact that Naomi often sees the world through a cinephile’s eyes (such as when she describes an Internet forum “that had the tone of a sixties French New Wave movie”) seems to be the author’s pretension and not the character’s. But Cronenberg is doing some complicated things with storytelling and truth in Consumed—things that only a novel could accommodate, at least on this grand of a scale. Of course, part of the reason for that is that grand-scale personal filmmaking is all but extinct. The fact that Cronenberg is a survivor of a lost era in which he used to be able to make big, weird, high-concept movies that only he could make—and now can pretty much only make movies about people talking in rooms—haunts Consumed’s cynical study of young, supposedly cutting-edge turks who think they have the upper hand over members of an older generation whose work is presumed to be somewhat obsolete.

Nathan and Naomi are intentionally shallow characters, and while their lack of substance makes sense once Consumed reaches its conclusion, for the first half of the book it can be tough to care about them enough to follow their lead down the story’s rabbit holes. The second act of the book is a particularly tough slog, saved only by occasional flashes of Cronenberg’s gift for articulating the oddness of sex. (One first kiss in particular is at once devoid of romance, charged with dread and revulsion, and like the flipping of a switch to illuminate a room that at least one of the characters never suspected existed.)

The novel becomes much more compelling once Cronenberg shifts away from the young couple. The most engaging, beautifully written chapters of the book are the two told in first person by Aristide, the ostensibly evil French philosopher, who has broken down and given Naomi the “confession” she came to Tokyo for. In this kind of novella within the novel, Cronenberg slows down the pace of the narrative considerably while also really exploring a character’s inner life for the first time. Aristide’s explication of the bizarre interconnection between a North Korean propaganda film and his wife’s certainty that she needed to have a breast amputated opens up into a meditation on the unlimited depth, and very specific idiosyncrasies, of a passionate long-term romantic love. Célestine and Aristide, we come to understand, were everything “Than” and “Omi” are not. Naomi’s “pics or it didn’t happen” digital-generation skepticism causes her to reject this live, oral autobiography, but ultimately she’s out-techno-futured. Naomi becomes a victim, but as a reader, you don’t empathize with her—Aristide is too seductive of a narrator.

In some sense the chapters are a detour, albeit an exhilarating one, away from characters with whom at this point even the novelist seems to be bored. But Aristide’s “novella” could also be considered the novel’s raison d’être, and it firmly confirms that Cronenberg is using the new-to-him format of the novel to take his career-long inquiries into the connections between bodies and technology into new places, accommodating new perspectives. Aristide may be a sociopath, but who cares when his point of view is so compelling? At least he’d never get swallowed up by a machine’s illusion—and Consumed is the rare Cronenberg work that, intentionally or otherwise, doesn’t elicit our identification with those who do. That’s definitely a new thing—but is it a good thing?

—

Consumed by David Cronenberg. Scribner.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.