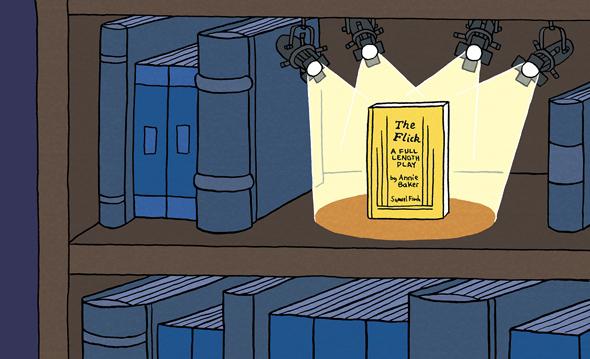

“Sam gets weird.” This stage direction, on Page 32 of the newly published script of Annie Baker’s Pulitzer Prize–winning play The Flick, reminded me in an instant why I love reading plays, why I’ll always love reading plays, even though I haven’t acted in a play since I was 21 years old. The stage direction, printed in italics as all stage directions are, appears when Rose, the projectionist at a crummy Massachusetts movie theater, mentions a tradition called “Dinner Money.” Sam, an experienced employee, has already started to befriend the newbie, Avery, but hasn’t yet told him about Dinner Money, so when Rose brings it up, Sam—well, the beauty of reading a play is that it is up to me what Sam does.

ROSE(to Sam)

Did you tell him about Dinner Money?

Sam gets weird.

SAMUh—what? No. Wait—

It’s easy when reading the scene to imagine the stammering awkwardness with which Sam hems and haws while Avery pretends not to be listening. But my response to the stage direction goes beyond envisioning Sam’s behavior into feeling it. I feel the low-level panic, the inability to navigate a difficult conversational shoal; I feel the impulse to just make noise, barely words at all, to try and make it through the next few seconds. Sam gets weird, it says, and who among us has not gotten weird?

In fact what I am doing in that moment of reading is acting. I’m not on a stage or in front of an audience; I am not even moving or speaking out loud. But that impulse—the natural reaction to someone else’s words, the innate urge to respond, the upwelling of intent—that’s the heart of acting. I may be acting silently inside my head, but in that instant, I’m an actor—a unique and rewarding response better elicited by published plays than by any other kind of literature.

Once upon a time, I was an actor, of a sort. I mean, I only ever got paid to perform in terrible dinner-theater murder mysteries, but I acted all through college, in Pinter and Anouilh and Shakespeare. I wasn’t all that great at it, but I loved it, and as a drama major I read a lot of plays. I read them searching for those moments when the play wormed its way into my body and provoked a response—a moment of connection to a character so bone-deep that I was that guy, even if just for a second, feeling the kind of Stanislavskian impulse I had so much trouble recreating on a stage. I bought plays at every used bookstore and yard sale I visited. I stocked the drama section of the bookstore where I worked and bought way too many with my employee discount. Sunday afternoons I’d visit the university library and work my way through a shelf, reading the first scene of each book to see which I liked best.

And though I don’t perform or direct or write plays anymore, those play scripts have always occupied prime real estate on my home bookshelves. Rows of thin spines, Samuel French or TCG or Faber and Faber editions, punctuated by the occasional fat Tom Stoppard: Plays 1 or Naked Masks. I still remember the pride I felt when a colleague who’d worked in the real New York theater visited my apartment, looked at the shelves, and approved: “When someone’s got Mac Wellman, you know they’re a real theater nerd.”

So the features of a published play are familiar to me, and opening The Flick for the first time I smiled to see the front-of-book once again: The PRODUCTION HISTORY, with its cast list for the first presentation of the play at Playwrights Horizons in New York, an acclaimed production I didn’t see but had read a lot about, including the email the theater’s artistic director sent to subscribers after the first few weeks of walkouts and complaints. The SETTING, in this case a dingy movie theater, placed onstage with the seats facing us as if we are the screen. The CHARACTERS, each with his or her perfectly offbeat descriptive note: Avery, who’s “in love with the movies”; Rose, who maybe “wears the same jeans every day”; and Sam, who, touchingly, “used to be very into Heavy Metal.” Already I was envisioning the set and casting the roles from the roster of human beings, actors and nonactors, in my head: Chris Pratt (pre–getting ripped) as Sam; my best friend from high school as Rose; as Avery, Slate’s Troy Patterson, as I imagine him circa 1996.

And then the play proper. A dramedy set over a few months entirely in that movie theater, as Sam, Rose, and Avery sort of become friends and then thrill, betray, and sadden each other in various ways. The dialogue, naturalistic and frank, is peppered with likes and ums, utilizing a slash in the middle of a line to signify an interruption. (I first saw that typographic guide in the plays of British super-genius Caryl Churchill, and now many playwrights use it.) And, of course, the stage directions, sometimes exceedingly particular and sometimes wide open for the reader’s interpretation—often both in the space of a single stage direction, as when Avery learns that Dinner Money is a scheme whereby employees of the theater skim cash off the ticket sales:

After a second, Avery takes of his glasses, wipes them off on his polo shirt, puts them back on, and then puts his head in his hands again.

Sam and Rose watch him do this, and then start mouthing panicky silent things to each other. Maybe Rose is mouthing stuff like WHAT DO WE DO??!! HE’S GONNA TELL ON US!! and Sam is mouthing stuff like IT’S COOL IT’S COOL I’LL TALK TO HIM IT’S GONNA BE COOL but we shouldn’t really be able to read their lips and maybe they can’t either, it’s more like mutual gestures of panic.

This mix of precision and shagginess epitomizes The Flick, in which Baker is always tracking the minute-by-minute emotional evolution of its three screwed-up characters, even while encouraging the happy surprises that make a play something special every night. A good actor or director reading that stage direction will be thrilled at its haziness, thrilled that it gives actors the ability to discover the moment in real time every night. On the page, it feels like an invitation to discover the moment on my own.

So reading The Flick, I acted it and directed it in my head. Early in the play, as Avery and Sam sweep out the theater, Avery, who’s only 20, asks Sam what he thinks he’ll do when he grows up. Avery’s impulse to ask the question makes sense; he’s still trying to discover who he is. But Sam’s 35, and he knows how incomplete he is, and he has not quite made peace with it, so I felt along with him the impulse to be offended at the question—and then the restraint it takes him to simply say, after a long pause, “… I am grown up.” He adds: “That’s like the most depressing thing anyone’s ever said to me.” But then, as they walk out of the theater, he says: “A chef.” Brain-directing the scene, I mentally underlined that detail, planning for the moment it comes back—maybe Sam goes to cooking classes and meets a nice girl and opens a restaurant. But no, Sam’s interest in cooking never comes up again. As the play went on, I felt viscerally how far he was from actually holding any real dream, and how much that hurts.

For a play about the aching human failure to connect in the face of the howling void, The Flick is really funny. And it’s funny in particularly theatrical ways—scenes that may already be funny on the page give the reader the chance to envision the very specific and funny ways they might play on stage as well. When cinephile Avery is drawn into a debate with Sam over the movie Avatar (which Sam defends), the rewards of reading Avery’s response are unique to the theater:

AVERY

I repeat: I don’t think it’s possible for me to engage in like a rational debate with you about it.

SAM

Oh come on.

AVERY

It’s like if I said: I love killing babies. Let me try to convince you why killing babies is fun and you should enjoy killing babies.

Read that exchange in a novel and the author might well feel the need to underline Avery’s absurdity, or at least hold it up for our judgment. Reading it in a play allows me to empathize with Avery’s cinephilic passion; to understand Sam’s delight at finding something to needle a new friend about; and, underneath those responses, to consider the way an audience would laugh twice at the line—once when Avery says it, and once at the stone-faced silence that Sam would surely offer in reply.

Reading Avery’s lines makes me inhabit him rather than look at him from the outside. He’s a snob with a creeping sense of his own worthlessness, a kid who just wants friends but shuts down around people. Reading The Flick reminded me of the importance of stories about people on the economic and emotional margins; it made me wince a lot about myself at 20, myself at 35, myself now.

Photo by Rachel Reilich

Reading The Flick is not a substitute, of course, for seeing it (or performing it). While the half-hour I spent reading it was a delight, the much-debated New York production was a more ruminative experience of about three hours. (Sounds wonderful to me.) Despite Baker’s many notes that the actors ought to take their time—“This might take a little while,” she writes, or “After about twenty seconds…”—it is impossible as an at-home reader to give nearly the breathing room to the play as a performance would. (One possible compromise: New York Times critic Dwight Garner’s dinner-party game, in which you read a play aloud while drinking. MWM, 39, ISO friends willing to do this with me.)

But a great published script makes you understand what the play is, at its heart. Not just what a certain production was like, though it also ought to do a good job of that. It makes you understand how the play feels as a living work of art—how it sounds and behaves inside your head, a mental effort that matters more in reading a play than in reading any other kind of literature. That’s an electric reading experience, and, given the quiet sales numbers for plays, a sadly uncommon one.

So stop by your local bookshop, or visit a great one online. Pick up a classic—Shakespeare, Chekhov, Strindberg, Churchill, Wilson, Kushner, Parks, McPherson. Or search out the play you’ve heard about but might never get a chance to see: This Is Our Youth, Hedwig and the Angry Inch, The Cripple of Inishmaan, Disgraced, The Village Bike, Wolf Hall, Sex With Strangers. Then read it—with friends, or with me, or by yourself. You may think you’re already an active reader, but you have no idea.

—

The Flick by Annie Baker. Theatre Communications Group.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.