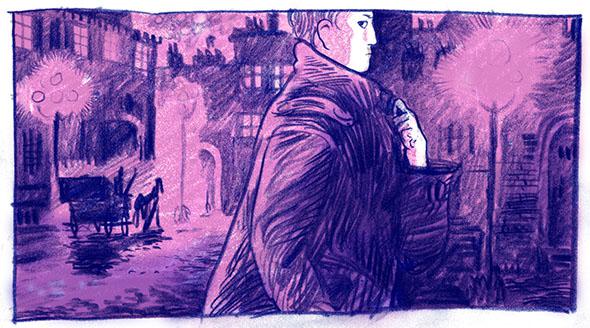

Some months ago, in a foul and nidorous vault, seated at a stone table near a pool in which some strange writhing thing turned slowly in the quag, a murder of marketers made a blood pact. They vowed to keep the plot of The Quick, Lauren Owen’s stunning debut novel, from the book-browsing public for as long as possible. As with The Crying Game and Haydn’s “Symphony No. 94 in G Major,” a surprise lurks within. But unlike those works, the surprise in The Quick changes entirely the sort of story it is, and they—the marketers—were betting that if you knew what it was beforehand, you might not pick up the book. Therefore: No mention of the secret appears in the blurbs or in the jacket copy, which present the novel as a Victorian thriller set in foggy Londontown.

Here’s the reason: The reader who will be drawn to the elegance of Owen’s language and her novel’s layered storyline is not the type of reader who will want to read what it’s really about.

What to do?

Well, if you want to persuade people to read the book, you don’t let on. You talk around the story, not to it. You keep the secret sub rosa. The publishers of The Quick got it. They knew that sooner rather than later the secret would get out, but they figured that by that time, readers would have generated enough heat to keep the novel afloat. They banked on those first readers falling so hard for the characters, that even when things took their turn, they’d hang on for the long haul.

And things do take a turn. And the publishers were right. People think they know what they want, but they don’t! They don’t know! You live your life, you get up and eat toast in the morning and go to work, you think you know what you want. And then, Lauren Owen comes along, puts all that stuff in a white glove, and slaps you across the face with it. You know nothing, sir! Nothing!

This is all to say this: I’m afraid that if I tell you what this novel is really about, you won’t read it, thereby missing a big, sly bucketful of the most tremendous fun.

I myself picked up The Quick for reasons ignoble: nice ’n thick; gaslit jacket art; slammin’ blurb by Hilary Mantel, Her Majesty of All Things Excellent in a Novel, Historical. At first, The Quick seems like a really terrific, plain old tale of yesteryear—à la John Banville or Peter Carey or Eleanor Catton, wunderkind author of The Luminaries.

Here’s what happens in the droll and moving (by turns) first 100 pages: It’s late in the Victorian era when James Norbury leaves his sister, Charlotte, at their family home to follow the muse poetic to London. He finds lodging, then love, and then poof—he’s gone.

This summation, of course, doesn’t speak to the heartbreaking poignancy of the love affair or to the deftness with which the sibling relationship is offered up, or to James’ melancholy, bred in his bones. At a dinner party, Owen writes:

James sat, unable to eat much more, and made a pretense of reading his menu, as dish succeeded dish. He had an odd sensation, watching the other guests eat—so civilized, and at the same time so barbarous, when one really thought of it. How much they consumed, and so politely, teeth and hands so busy, knives slicing.

Indeed, if I have a criticism of the book, it’s that Owen rushes it a little—these first hundred pages—to get to what interests her more. Even so, as Part 1 ended, I was as pinned as a beetle in a cabinet of wonders.

And then things took their turn. I fled to Facebook to whine.

Generally, I like to find my horror in the world around me (war, melting ice caps, the NRA) rather than in my books. But I get it: Writers gonna write, and if you’re hooked, you’re gonna follow. So, I followed.

And anyhow, listen: If you’re too nice (in the Victorian sense) for fantasy, you’ll miss out on Margaret Atwood’s splendid MaddAddam trilogy. If you’re too effete for fantasy, then nope, no Angela Carter for you. If you’re too fancy for fantasy, well then you’re in danger of living your life minus the supreme pleasure of Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell and Elizabeth Kostova’s The Historian, which I read in the pool of a Mexican resort because I couldn’t put it down. If you’re not too fancy for a little fantasy, well then skip the rest of this review and quick, go get The Quick.

Because it’s at this point in the book that things begin to really rollick. The London-based Aegolius Club is not your average exclusive brandy-steeped, dark-paneled gentleman’s club, no indeed. Entrance to such a club as this requires a certain pallidness, an achromasia, a terrific effeteness peculiar to the very high-born undead. Here’s where James ends up. And here’s where his sister, Charlotte, rushes, unlikely hero that she is, to rescue him.

Charlotte is awkward, self-conscious, hesitant, sweaty, respectable, and driven by a sort of Christian guilt to save her brother who, duh, can’t be saved. (Or can he?) I’ve always appreciated a good sister-champion; Charlotte is particularly appealing for her sense of mission and her quavering ladylike courage. Her internal observations make for some of the most slyly entertaining reading in The Quick. “Wealth instilled confidence, of course,” she thinks, as a new acquaintance uses someone else’s kitchen without asking. “One could make free with others’ possessions then, because one would always be able to replace them, if necessary.”

Owen honed her ability at the adventure story while writing Harry Potter fan-fiction as an adolescent. She weaves what’s here with what’s beyond as easily as J.K. Rowling does, and as with Rowling, she seems to feel particularly at home with the beyond. Some readers will undoubtedly feel that they’d rather wait to read Owen when she gets over her attraction to the supernatural, as Rowling has (for the moment, anyhow). But just like literary fiction, the world of fantasy has its hacks and its artists, and the task of a reader ought to be finding the artists, whatever they’re writing about.

Photo by Urszula Soltys

For The Quick, Owen invented a whole society of fiends who dwell among us simpler, weaker, quick-blooded types (their supper). But, while all of Owen’s monsters are of the Transylvanian variety, they’re separated from each other by birth, education, pocketbook. And let’s just say that the effete Aegolians and the streetwise Alias don’t exactly get along. Class warfare’s generally good fun; in this particular case, it’s a little hard to root for either of the fanged camps, as both would like to have Charlotte and her allies for their tea. A character called Doctor Knife is among the reasons for the extremity of their antipathy for each other. Doctor Knife is one of “the quick,” that is, a regular old guy of the warm-blooded persuasion. But the Aegolians use him to do their research for them, and the Alia kids he takes as subjects, like urchin-bloodsucker Nick, whisper about him:

Nick had told all the kids the story of Doctor Knife. He was a small and grayish fellow—nothing out of the ordinary until you got up close.

“Then you see his eyes,” Nick had said.

“ ’E’s one of the Quick, though, ain’t he?”

Nick nodded. “Makes it worse. Means ‘e don’t want us to eat, whatever ‘e wants us for.”

Apparently, even the dead get creeped out.

It’s not uncommon for a debut writer to run amok toward her novel’s conclusion, especially when things begin to rip and roar, but Owen remains in control of the action to the end—which is particularly vital, as The Quick seems to be the beginning of something rather than a whole unto itself. Due to the fact that the first draft of the novel logged in at more than 1,000 pages, the publisher’s given us only the first half of the manuscript. So the sequel’s more than in the works. Soon The Quick will hurtle into the 20th century, where it will apparently rise again, revivified. And I’ll be waiting.

—

The Quick by Lauren Owen. Random House.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.