The Magicians, The Magician King, and The Magician’s Land together tell the story of the strange life of an overachieving Brooklyn high school student named Julia Wicker. (Yes? All agreed? Good.) Here we can at last straighten out Julia’s experience through the first two books, kinkily though Lev Grossman tells it, acknowledging that readers might not wish to know yet the details of what happens to her in the third book before it comes into print on Tuesday.

Julia is dating a normal bro her senior year when suddenly she and her boyfriend’s irritating nebbish best friend, Quentin Coldwater, who has a ridiculous crush on her, are spirited away to a magical academy. Literally, Brakebills is a magic college—the only one in North America. Julia fails the entrance examination, and somehow Quentin is accepted, and Julia’s life goes off the rails. She’s been ensorcelled to forget she was ever summoned, but it doesn’t quite take. Although one of the pluses of being rejected from Brakebills is that they then jury-rig your admission to seven very good colleges, she forgets to go, and then forgets to bathe; she just can’t shake that thing. She forages her way deep through the Internet on the trail of magic, stalking head shops and restaurant supply stores. Her parents freak. At 18, she gets stuffed in the nut hut for six weeks.

She moves out and becomes a temp, and finally, at last, she finds one fragment on the Internet that’s really unreal. It’s either magic, or she’s finally cracked.

And so she sets her sights on Quentin, who is long missing. The only way to find Quentin is to stalk his ignorant parents, who’ve moved to some tacky suburb in Massachusetts. She waits a year and a half. He finally shows up on summer break, and she follows him to a cemetery. She tries everything, including dangling herself before his crush. And he shoots her down and takes off—although at least he confirms she’s not crazy, that there really was a magical college, and that she really didn’t get in.

Julia—or at least “the wreck of the good ship Julia”—goes home. Her parents are thrilled. She feels, at last, relief, and also the blunt edge of 450 milligrams of Wellbutrin b/w 30 milligrams of Lexapro. She reactivates her acceptance to Stanford. She also finds a kooky anonymous online group of 14 addled misfits, who protect themselves behind walls of tests and clues, and who become her all day, everyday chat-room pals. One day on one of her long recovery walks in her new and acceptable life, she encounters a numerical pattern series IRL that was part of a game they’d played online. It delivers her to a shabby house in Bed-Stuy, where suddenly she can smell magic, and then the madness is upon her again.

There she begins learning, and, outgrowing this shabby house of magic, she begins traveling house to house, from Buffalo to Key West, finding these locations by friendliness or via “the power of the bathroom handjob.” The quest leaves her emptier and emptier. At last, an advanced magician shows up and runs Julia through a test of all her spells, and then leaves her clues to get to a village in the south of France, where she finds 10 people, half of them her friends from online, who are, of course, magicians as well as geniuses and medicated depressives. She’s upset, stunned, and gratified. Most of all, she’s saved. They teach her everything they know, and then they add her to their quest: What is the “magical singularity”? What is the next level, what is beyond? The central mystery being: What is the nature of magic, and how much of it do we know? Is there always more and more powerful magic to be discovered? Or do you meet up with “inverse profundity,” in which it turns out that our magic is just a series of sad little power tools that a stronger race have accidentally left behind? The answer isn’t, they’ve found, traveling nearer to the center of the Earth, or dreams, or the magnetic field, or space. All that is left to explore is religion.

Julia eventually gets on board, and they tromp the countryside digging up strange minor deities and a hermit and some critters. As they work, Julia begins to believe that underneath all the religious blah-blah of our world there actually is something, a guiding but local hand of a goddess, an actual hand of nature and the seasons, “a distant cousin of Diana or Cybele or Isis.” The hermit gives them an invocation. They prepare, wearing white flowing gowns: a crown of mistletoe, a silver bowl of rainwater, six animals for slaughter. Even as they begin, Julia realizes she doesn’t actually care. All she wanted was a family of her own making, and here she’d found it at last! But the ceremony goes on, and, instead of this goddess, out from a candle pops a 12-foot tall man with a fox’s head. Then the killings begin. Only two survive, and Julia is one. But does she? While the fox god rapes her, he gives her some power, but takes something more complicated—something she wasn’t sure she had but definitely wouldn’t have given up.

(The rape is the dodgiest event of the three books, it seems obvious to say. On the plus side [I guess?], it seemed to settle the question of whether we were reading a book for young adults or for actual adults. [“Am I a young adult author? Hell if I know,” Grossman wrote once.] As for the minus side … most everything else? Nobody may issue a blanket proclamation that says, Yes, this particular use and description of violence is kosher, except each of us for herself as a reader or writer. This is a jury that must forever be out. Some found the rape upsetting but not necessarily exploitative; after all, this is a series where someone gets his hands eaten off, so it’s not out of left field. It is likely what it is meant to be: Horrifying, grotesque, unreal, real. And yet. [Really great analysis can be found here, here, and outragedly and wonderfully here.])

By chance, possibly, Julia then meets Quentin’s friends Eliot and Janet, in, of all places, a high-end spa in Wyoming. They’re attracted to her because she’s obviously a hot goth mess, but then Eliot spies her doing magic—dark magic, a Karen Silkwood shower of magic, as you might imagine. They adopt her and spirit her out of the world, and Julia becomes a queen of Fillory, which is a magical other place, made famous by Narnia-esque children’s books on Earth, books stupid Quentin’s been obsessed with his whole life; finding that Fillory existed was what rescued Quentin from his own life of depression. This and that and the other thing happens. All along Julia has been changing. She has stopped using contractions in her speech; she has also gone pretty fully interior and also really all the way goth on the exterior.

Unfortunately the magic button they once all used to hop worlds has gone to a new owner, and they learn that gateway between worlds is rather busted up. That was Julia’s doing; she and her friends, by their summoning, have given notice to the greater pantheon beyond our world that humans have been stealing magic. They interrogate a dragon in Venice’s Grand Canal, who actually sort of usefully explains some things: “The old gods are returning,” and “the first door is still open.” They find that first door and float through to the other side, where they have missed most of a quest to find seven golden keys, but finally do find them, after much ardor and barter. The dragons save magic! More importantly, it turns out this goddess does exist, and she transforms Julia into something divine. She ends up whole, and also important. Her suffering has meaning. Does yours? I’m not sure about mine.

* * *

You might also think of these books as the story of Alice, who comes to Brakebills with Quentin; they slowly become each others’ first loves. She spends seven years traveling through space and time as a blue flaming creature of magical rage.

Or you could think of these books as the story of lands and magic themselves—after all Julia and her friends, in performing that first summoning of a god in thousands of years, have attracted the notice of those operating at the next level, who then break the pathways between the worlds and possibly even the world of Fillory itself.

It’s definitely not the story of big queen Eliot, though. (Though at least he sort of barely kinda gets to have sex once, in a scene nicked from Proust, no less.) That story wouldn’t be very marketable, would it?

But you could also think these three books are the story of Quentin, since most of the actual words are about him. But why would you? The thing about this Quentin fellow is he spends basically all three books accidentally and unhappily hopping in to and out of Fillory. He’s a little brat about it, and everything else, mostly. He comes and goes so many times you’ll lose track. He’s a huge pinhead about his relationship with Alice. By the end of Book 2, he’s finally sacking up and learning to not be a giant baby. But that’s a little late, honestly?

And his Fillory obsession! Jesus. Fillory sucks, in the same way that Narnia and France suck too when you get up close. Literally the only thing that recommends Fillory is that everything is magic there. Some of the animals can talk, and some can’t. Why? Plus there’s dwarves under everything, but you never see them. The kings and queens of Fillory, including Quentin, and less so, Eliot, our louche homosexual pal, and Janet, the super-bitchy bossy one, are seriously not ideal for the job.

Yes, it’s a monarchy. What’s worse than a monarchy? Oh, right, a false monarchy that’s actually ruled by two stupid god-sheep who are just phenomenal assholes.

But mostly it’s Quentin. Who gives a damn about Quentin in the specific and Quentins in general? “Boys were so unstable that way, full of buggy, self-contradictory code, pathetically unoptimized,” our hero Julia thinks at one point, after sleeping with someone she actually likes and watching him go cold and shut down. They certainly are, if they refuse to get their shit together. And if they don’t want to get their shit together, who would want them? If all three books are actually about Quentin finally finding a reasonably appropriate level of adolescent maturity by the age of 30, and that’s not somehow remarkable, then, boy, are we ever in trouble.

* * *

It is queerly difficult to remember these books not so long after reading them. They evaporate, in a not unpleasing way, leaving a sense of having had a nice steak, or a decent massage. It’s almost as if the books had a spell on them, leaving them incapable of being recalled. That’s partly the function of publishing over years as a trilogy.

How should we judge a trilogy? Let’s say you get three magic questions, which is always the kind of dumb jerk thing that happens in a magical land. How about: Are these people still actually behaving like themselves—or at least like people—throughout? Am I satisfied? And, hmm: Is this world complete?

Trilogies have gotten a bad rap, and rightly so. The blockbusters in YA SF and fantasy suffered horribly having to perform throughout three books. Both Hunger Games and Divergent in particular went badly nuts in their third acts, all the plots squeaking like squeezeboxes, all the characters dripping blood and tears endlessly. Their heroes stopped being women and started being devices. (So much “torn between two lovers” garbage, too! Blecho!)

It’s likely always been this way. “The reason people don’t believe that I didn’t plan a trilogy from the start is that fantasy now suffers from endemic trilogitis,” Ursula K. Le Guin wrote about the time when it looked like her Earthsea series was going to be a trilogy. “Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings is largely responsible for this epidemic.” The Earthsea books are useful to consider in context of the Magicians trilogy. They were published over the course of 31 years, and the first three are, largely or entirely, about a man. When the fourth book, Tehanu, came out, Le Guin later wrote in its afterword, “some reviewers and readers were disappointed. … Where’s the guy with the shining staff? Who’s going to do the big magic? A little girl? Oh, come on. That’s not a hero tale! … Some readers who identified with Ged as a male power figure thought I’d betrayed and degraded him in some sort of feminist spasm of revenge.”

Such a heroine, a woman of importance, just hadn’t really existed yet in the marketplace. We live now in wealthy times of female heroes, particularly in trilogies. One thing they have in common is that, unlike Quentin, they all grow up pretty fast. They have to.

“When I was writing the story in 1969, I knew of no women heroes of heroic fantasy since those in the works of Ariosto and Tasso in the Renaissance. … The women warriors of current fantasy epics,” Le Guin wrote in an afterword of The Tombs of Atuan, “look less like women than like boys in women’s bodies in men’s armor.” Instead, Le Guin wouldn’t play make-believe, and her women were sometimes vulnerable, including physically. She refused to write wish fulfillment, even the wish fulfillment many of us crave. This seems relevant to how many of us felt angry about Julia. I have seen dozens of Tumblrs about young women throwing Book 2 across the room, or at least writing of closing it quietly and dispiritedly. We wanted her to rage and triumph. Instead, she got raped, while Quentin got a fucking crown. Thanks, man.

Le Guin’s beliefs have some children now. Kristin Cashore’s wonderful Graceling Realm series, three books to date, is set in a small and rather medieval land, where all is as it should be except there are various stripes of mutants (as well as various familiar forms of gender-based roles and restrictions). Each of the three books is led by a woman: the first is a Graceling, a being magically imbued with a special talent; the second is a monster, who is attractive to the point of compulsion; the third is an ordinary girl queen. These are all real women, and these are emotional and strong and ultimately bizarre stories. In Laini Taylor’s exquisite Daughter of Smoke and Bone trilogy, the story blossoms perfectly, never rushed or forced, and the more extreme and strange it becomes, the more the humanity in it resonates. (Strange, you say? Why yes, it’s about a cool girl at an art school in Prague who was raised by a chimera in another dimension whose job it is to collect teeth from the Earth for a war against the angels! Yeah, buddy.) Throughout the action and history and madness, she always remembers to tend to her hero’s heart.

Real women are everywhere, even written by men: Scott Westerfeld’s thoughtful and often hilarious Uglies trilogy-plus-one holds up throughout. Jeanne DuPrau’s City of Ember series is four books, although the third is a very frustrating prequel, but it has a thoughtful, inquisitive, and realistic lady hero.

Cassandra Clare’s quite popular and inventive Mortal Instruments series was supposed to be a trilogy and blew out into six books, and is also instructive to view in light of the Magicians books. Grossman’s early unveiling of his story is so well-handled, as Quentin McJerkface blunders into a land of actual magic; in comparison you see the hasty machinations right in the opening of City of Bones, the first book in the Mortal Instruments, as A Supposedly Normal Girl is surprised to fall into the supernatural on literally Page 4. Who is she? Well, it doesn’t matter, does it, because I guess she’s just supposed to be you, young lady book-buyer, and you’ll take what you can get. Oh no? Those days are over? Oh good.

* * *

The more you look at them all, the more you can see just how terrifying embarking on a trilogy must be. Every author must feel like a passenger landing a plane. There’s plenty of literary wreckage all around. Those who stick the landing deserve applause.

When read straight through, the Magicians trilogy reveals its lovely shape. The world of the books wraps around itself, exposing most everything necessary by its conclusion, but occluding operations that we’ll never need to see. There’s still a series of mysteries and untold tales left unknown deep inside the books, but that’s mostly OK. (Some day, some day, though, The Book of Alice.) But we here in reality have our own unknown mysteries as well. Also, this shape means that it’s far better read straight through than it is read separated by its publication dates. Things you will definitely have forgotten were meaningful—emotionally—turn out to be important, and addressed, and redressed.

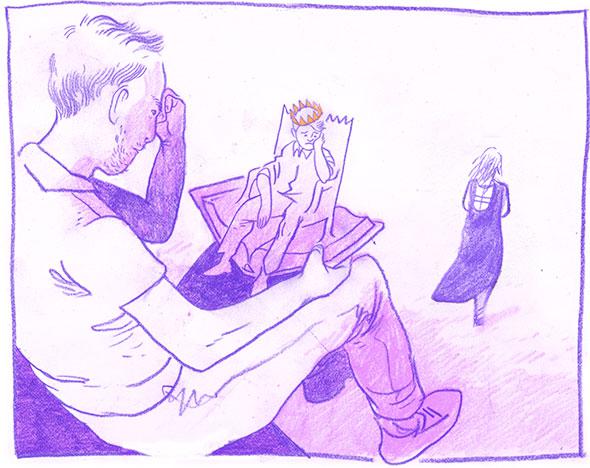

Courtesy of Mathieu Bourgois

Grossman, if you read his blog and his Twitter, spent most of the last six or seven years in a constant state of writing panic. (Well, he also had a second—and then a third!—child. So he probably brought much of that on himself.) It was surely worth hammering his way through, at the very least to be spared the kind of wrath reserved for the old slowpoke George R.R. Martin. And if you listen to him, he did not know, it sounds like, where he was going with these books. “Basically what I’ve been doing is,” he wrote back in 2010, “I’ve written about four-fifths of the plot, and I’ve been trying to get ready to write that critical last fifth. But I can’t do it till the first four-fifths are really working—all the characters make sense as people, all the scenes connect up in a coherent arc, I have some idea how the little details I’ve planted throughout are going to pay off, and so on.” Emphasis mine.

“People like to believe that writers know exactly what they are doing and have their story under control, thought out, plotted from beginning to end … ” Le Guin wrote, in an afterword to The Farthest Shore, but she certainly did not. It’s not control that’s important, was her point: “There’s a difference between control and responsibility.”

Grossman had a responsibility to Julia, and to Alice, who are the ones who suffered the most in his story. He had a responsibility to all of them. Did he do right by them, in the end? You might not have thought so at the end of Book 2. When you reach the conclusion of The Magician’s Land, it’s possible you will.

* * *

It sounds here like I’m taking Grossman to task for being a boy writing a book about a boy. I’m not, because he’s not Quentin. He’s Julia.

“What did I do all day, or all night, since I rarely got up before 2 in the afternoon, or went to bed before dawn? There was no Internet. I had a TV but no cable, and the TV was black and white and only occasionally got reception. … Somehow I managed to dispose of the time. I burned it down or threw it away or dumped it in the river, week after week after week,” Grossman wrote on his blog once, explaining a bleak period in his younger life between Yale and Harvard. (I know, I know, but it really does sound bleak. Pain is pain, people.)

And here’s Julia, from The Magician King, on her days after high school:

Julia would do anything to make the time pass. She killed time, murdered it, massacred it and hid the bodies. She threw her days in bunches onto the bonfire with both hands and watched them go up in fragrant smoke. It wasn’t easy. Sometimes it felt like the hours had ground to a halt. … Online Scrabble helped ease them on their way, and movies. But you could only watch The Craft a finite number of times, and that number turned out to be about three.

So Grossman is writing Julia from his truest self. That’s why she’s a person, not a “girl,” not boobs with a wand, and not a male character dressed as a woman, in Le Guin’s formulation. That’s why the books are about her.

Over and over again in the books Grossman returns to the idea of life as a story. This is a common misconception of what human life is. Story is Quentin’s sad obsession. Quentin is Grossman’s other worse self, his irksome childish self who constantly tries to make a narrative out of the mess of everything, while Julia is busy lighting everything on fire and climbing in after it.

Here’s Quentin, at the end of Book 1, hunting a white stag:

He was on a quest, but it was his quest now, nobody else’s. He scanned the skyline for the prickle of its antlers and thickets for the flash of its pale flank. He knew what he was doing. This was what he’d dreamed about all way back in Brooklyn. This was the primal fantasy. When he had finished it, he could close the book for good.

Here’s Quentin, near the beginning of Book 3:

It was crazy to think that the others were still over there, riding out on hunts, receiving people in their receiving rooms, meeting every afternoon in the tallest tower of Castle Whitespire. And Julia was on the Far Side of the World doing God knew what. But that had nothing to do with him now. After all that it turned out that wasn’t his story.

That wasn’t his story. And 30 pages later:

His own transition from Brakebills to the real world hadn’t exactly been graceful either. When he graduated he’d thought life was going to be like a novel, starring him on his own personal hero’s journey, and the world would provide him with an endless series of evils to triumph over and life lessons to learn. It took him a while to figure out that wasn’t how it worked.

At last. It’s crucial to Quentin’s growing up that he be released from this stupid compulsion to make sensible stories that resolve, and most importantly, to let go of his need to form self-soothing narrative concepts of self. Momentousness, epicness, heroism, so common in young adult and fantasy fiction, are poison. They will make you wistful, falsely pre-nostalgic, soul-sick. Life isn’t that. The desire for the clarity of your own tale is infantile selfishness. It’s a nervous tic evolved from being crippled by fear. If you think your story will make sense in retrospect, perhaps you’ll get lucky at the end, but you’d better be dying quite slowly.

As Quentin is first being whisked off to Brakebills, he’s also given a manuscript. It’s the missing sixth book in the stories for young adults written about Fillory, and it’s called The Magicians. When Quentin reads it, it’s not very good. Later on, Quentin gets his hands on another Fillory-related book—the journal of one of the children who’d actually been to Fillory, the children whose real lives had provided the fodder for the Fillory fantasies. It is reprinted in full in The Magician’s Land. It’s a man made into a story and trapped inside. Needless to say, it’s a tragedy. But for Alice and Julia and, yes, even our dumbass Quentin, at last, they don’t need to worry about the stories of their lives. Their tortures, unlike ours, are over.