Those who claim we are witnessing a new Gilded Age need look no further for proof than the companion books to three recent exhibitions showcasing jewelry. Two of them—Gilded New York: Design, Fashion, and Society and Beauty’s Legacy: Gilded Age Portraits in America—revisit the original Gilded Age, with its jeweled lorgnettes, chokers, watch fobs, and ascot pins. The third, Jewels by JAR, brings this more-is-more aesthetic up to date with a veritable orgy of wearable wealth, custom-made for an exclusive international clientele over the past 35 years. The books illustrate that while diamonds may be forever, the politics of wearing—and, indeed, exhibiting—expensive jewels are dangerously volatile.

New York, where all three shows originated, has always been the standard-bearer of bling. Fifth Avenue jewelers like Tiffany, Dreicer & Co., and Black, Starr, & Frost flourished in the Gilded Age, spinning the straw of newly and dubiously acquired fortunes into glittering garlands of gold. A French visitor, fin-de-siècle novelist Paul Bourget, testified to “a profusion of jewels worn in daylight. At noon they will have at their waists turquoises as big as almonds, pearls as large as filberts at their throats, rubies and diamonds as large as their finger-nails.”

By “they,” of course, he meant the ladies. Like modern-day Real Housewives, Gilded Age matrons were celebrities whose every move was analyzed and imitated by a hate-watching public. Jewels were more than a fashion statement; they functioned as a bank statement. Quantity trumped quality. Gilded New York chronicles an 1874 party at which Caroline Astor was decked out in diamonds from head to toe; even her shoes were bedazzled. Mrs. George J. Gould changed her jewels several times a day, like an actress changing costumes between scenes—a habit acquired, perhaps, during her premarital career on Broadway. Her collection was so vast that she had her own storage vault at Tiffany. Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish once spent $15,000 on a diamond dog collar—an actual collar for her dog, not the fashionable wide necklace of the same name. Even crosses (such as the one modelled by singer Emma Cecilia Thursby in Beauty’s Legacy) were diamond-studded and the size of doorknockers.

New-York Historical Society, Gift of James Hazen Hyde, 1949.1

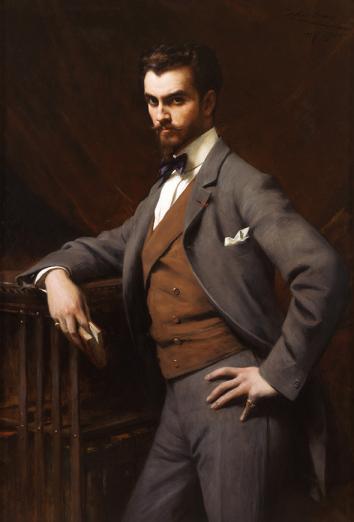

But men sparkled, too. In Théobald Chartran’s portrait, James Hazen Hyde sports a chunky ring on each pinky finger and a pearl pin on his bow tie; his supercilious air and trim goatee evoke both a Medici and a Mephistopheles. (Soon after the portrait was painted, Hyde fled to Paris to escape a Lehman-like financial scandal.) The enormous gold watch fob Samuel Ward McAllister, the self-appointed gatekeeper of the Four Hundred, sports in his 1877 portrait by Adolphe Yvon is set off by his sober black bespoke suit. As Valerie Steele points out in her essay in Beauty’s Legacy, men were usually more discreet in their ornamentation. Perhaps McAllister was compensating for the fact that his wealth came from his wife?

Affluent New Yorkers saw themselves as American royalty, and openly emulated the tastes of Europe’s crowned heads—with the key difference that their jewels were bought, not inherited. (When the French crown jewels were auctioned off in 1887 after the fall of the Second Empire, Tiffany & Co. was the largest single buyer, snapping up a third of the lots.) Nothing advertised that one was American royalty better than a tiara. No longer reserved for queens and princesses, the tiara crossed over to American drugstore heiresses in the late 19th century, as impoverished aristocrats liquidated their family treasures. By 1894, New York was home to nearly 100 tiaras, according to Gilded New York; many more followed after the introduction of inheritance taxes in Britain that year.

If diamonds and pearls dominate portraits of Gilded Age New Yorkers, it is because they featured prominently in portraits of Elizabeth I, Empress Joséphine, Queen Victoria, and other royal role models. Consuelo Vanderbilt—who married her way into the British aristocracy, becoming Duchess of Marlborough in 1895—draped her famously swanlike neck in a 19-row pearl dog collar and two long strands of pearls; one had belonged to Catherine the Great and the other to Empress Eugénie. The first diamond strikes in South Africa in the late 1860s made diamonds plentiful to the point that their value threatened to plummet before the market was artificially stabilized in 1888. But pearls never recovered from the advent of commercial cultivation around 1916. Fifth Avenue jeweler Jacob Dreicer had once spent decades assembling a rope of perfectly matched natural pearls worth $1.5 million. What was the point of wearing pearls once even the middle classes could afford identical, cultivated copies? Tellingly, Joel A. Rosenthal—the reclusive designer behind JAR—refuses to work with cultivated pearls today, instead collecting antique, natural pearls to use in his oversized pendant earrings and gobstopper rings.

Lavish masquerade balls provided an excuse for Gilded Age hostesses to play queen for a day, wearing even more jewelry than usual. At the legendary Vanderbilt Ball of 1883, Cornelia Bradley-Martin—dressed as Mary, Queen of Scots—wore a “head-dress of ruby velvet, embroidered in pearls,” the New York Times reported. (The Bradley-Martins had a castle in Scotland.) In 1897, Mrs. Bradley-Martin realized a long-cherished ambition of throwing her own ball. The country was just emerging from the depression triggered by the Panic of 1893, and many whispered that the event—with its estimated cost of $250,000—was an ill-advised display of wealth. But Bradley-Martin protested that it would boost the local economy. This philanthropic impulse was somewhat undercut when she greeted her guests in a necklace that had once belonged to Marie-Antoinette—a sartorial invitation to let them eat cake. The ball marked a turning point in the public’s perception of New York’s elite, from escapist entertainment to something more sinister.

As rapid industrialization widened the income gap in the 1890s, jewels, balls, and other luxuries came under increasingly close scrutiny. “Could the wealthy justify extravagant expense on entertainments by claiming that they were putting their money into circulation?” Susan Gail Johnson asks in Gilded New York. “Or were they flaunting their wealth in the face of those less fortunate?” Jewels—whose only purpose was to impress—became politically incorrect to wear outside of the most rarefied circles, a paradox that persists today. Jewels by JAR is conspicuously coy about the owners (and price tags) of the pieces it showcases; the private collectors lending to the show remain truly private. Similarly, Gilded Age matrons sometimes kept their jewelry purchases under wraps for years, lest they be accused of showing off, and newspapers had to speculate about the value and intended recipients of the baubles displayed in shop windows up and down Fifth Avenue. Though household servants could be bribed to leak details of purchases to a ravenous public, “precise information remains tantalizingly scarce” even today, Jeannine Falino laments in Gilded New York. Much of the information we do have is demonstrably inaccurate: The press reported that the famous “Electric Light” masquerade costume Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt II wore to the Vanderbilt Ball of 1883 was trimmed with diamonds, but in fact they were crystals set off by silver foil—as visitors to the Museum of the City of New York, where the actual gown was recently on display in all its twinkling glory, could see.

Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Countess Laszlo Szechenyi, 51.284.3A-H

These books offer a seductive through-the-keyhole glimpse of the gemstyles of the rich and famous, but there is another, more compelling narrative lurking beneath the shiny surface. Implicit in all three is the redemptive story of intrepid American artisans beating their European competitors at their own game. In the early days, New York jewelers did their best to fool their customers into thinking they were actually in Europe. Dreicer & Co.’s gallery was a replica of a salon at Versailles; Theodore B. Starr offered two viewing rooms, one in the French Louis XVI style and the other in the English Adams style. From pretending to be Europeans, American jewelers progressed to conquering Europe. Tiffany & Co. opened a Paris branch as early as 1850 and a London outpost around 1870. Bronx-born Rosenthal never worked in New York; from day one, JAR has been based in the Place Vendôme, the Parisian cradle of haute joaillerie.

Beginning in the 1880s, American jewelers began to develop their own style, promoting native stones and liberating women from the colorless (if regal) monotony of diamonds and pearls. Tiffany’s George Frederick Kunz singlehandedly launched the trend, using Montana sapphires, pink Maine tourmalines, and Mexican fire opals; he even exhibited his vibrant pieces at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900. (Today, JAR continues the tradition by spurning conventional gems in favor of colorful semiprecious stones like tsavorite garnets, fire opals, and black spinels.) Rather than being sold on the strength of their illustrious provenances, royal jewels were more frequently broken up and reset for modern American tastes. By the early 20th century, American clients felt confident rejecting French Art Nouveau jewelry in favor of homegrown interpretations by Marcus & Co., F. Walter Lawrence, and Louis Comfort Tiffany.

Courtesy of Tiffany & Co. Archives, A2000.16

After all, what Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner dismissively dubbed the “Gilded Age,” art and architecture historians have since hailed as the “American Renaissance.” It was an era that saw not just the apogee of conspicuous consumption, but the triumph of American design, and the formation of the great private art collections that now fill our public museums. Perhaps the American Renaissance itself is due for a renaissance, one fueled by internet IPOs and real estate booms rather than robber barons. Moguls-turned-museum founders Alice Walton, Paul Allen, and Eli Broad might argue that just such a renaissance is already underway.

But jewelry exhibitions remain an uneasy prospect for museums, if only because curators must often depend on the jewelers themselves to provide access to priceless pieces. Gilded New York is sponsored by Tiffany and inaugurates the Museum of the City of New York’s Tiffany & Co. Foundation Gallery. Jewels by JAR had its own pop-up gift shop and trunk show at the Metropolitan. Critics slammed the museum for mounting such a blatantly commercial show, the Met’s first-ever retrospective of the work of a living jeweler. Yet it’s difficult to imagine who could actually afford to buy the wares—and easy to be blown away by the no-expense-spared artistry on display. Does Rosenthal’s insistence on using natural pearls make him a snob, or a perfectionist? Would newspaper readers of 1883 have been comforted or cruelly disappointed to know that Mrs. Vanderbilt’s dress was with trimmed with crystals, not diamonds? Rather than harbingers of revolution, these gems of books challenge us to admire over-the-top jewels as the ultimate high-wire acts of design.

—

Gilded New York: Design, Fashion, and Society, edited by Jeannine Falino and Donald Albrecht. The Monacelli Press.

Beauty’s Legacy: Gilded Age Portraits in America by Barbara Dayer Gallati. GILES and the New-York Historical Society.

Jewels by JAR by Adrian Sassoon. Metropolitan Museum of Art Series.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.