A giant walks into a bar. Orders a big glass of booze. Across the room, two barflies size him up. “Man, he is really a freak. For real,” one guy says to the other guy. But his buddy’s seen the giant stomp around the local wrestling ring, and he’s dismissive. “If you watch closely, they never even hit each other,” the guy says. “That wrestling shit? It’s fake!!” So the bartender says, “I’d shut up if I were you,” and the guy, he says, “What’s he gonna do?? Fake fight me??” The giant stands up. The guys flee into their car. The giant flips the car onto its roof.

At least, that’s how the story goes in Box Brown’s new comics biography of André Roussimoff, the 7-foot-4, 500-pound man who performed as Géant Ferré, Giant Machine, Monster Roussimoff, and Monster Eiffel Tower before cementing his legacy as André the Giant, the “eighth wonder of the world” and perhaps the most famous professional wrestler who ever lived. André the Giant: Life and Legend attempts to tease André Roussimoff the man out from André the Giant the brand and, along the way, peel back the artifice of professional wrestling to reveal its consequences outside the ring.

Brown admits upfront that the task of capturing Roussimoff’s larger-than-life story into his puny black-and-white panels is almost inconceivable. “Yes. It’s ‘fake,’ ” Brown writes of wrestling in the book’s prologue. In an industry where the truth is “elastic” and the narrative is bent to promote the wrestler “as a product,” all wrestling backstories require a deep dive. But “stories about André the Giant can be especially hard to judge,” Brown writes. “Stories about him were unbelievable just due to the extraordinary circumstances of his life.” Everything we know about Roussimoff reads like a tall tale.

When Roussimoff became the Giant in 1973, most fans had wised up to wrestling’s tricks, but the wrestlers themselves never told. (That bar scene played out in 1960s Paris, where Roussimoff—who had previously put his body to use as a farmer, woodworker, factory worker, and furniture mover—got his break.) Roussimoff worked in the heyday of “kayfabe,” a wrestling term bummed off of an old carnival tradition to describe the performer’s commitment to suspending disbelief in front of his audience. In Roussimoff’s day, “for a wrestler to come out and admit that wrestling is not actually a real fight would be breaking the social contract,” Brown writes. Revealing the mechanics of the craft “was simply not done.”

It wasn’t until the 1990s that the curtain got tugged back an inch. When state athletic commissions attempted to impose standards on professional wrestling, the WWE’s Vince and Linda McMahon—who had consolidated regional wrestling competitions into a national scheme, and introduced them to a syndicated television audience—argued that their version of wrestling constituted entertainment, not sport. That allowed the organization to get by without conducting physical exams of wrestlers, employing ringside doctors, or submitting to state athletic board supervision—but it also cracked the fourth wall. The Internet’s rise demolished the facade. And the McMahons quickly converted the end of kayfabe into a lucrative exposure opportunity. The WWE began producing wrestler “shoot” interviews where performers spun yarns from beyond the mat, and sold its own videos and books codifying the tales. Professional wrestling matches may have been choreographed, but these behind-the-scenes tell-alls were supposedly unscripted—about as real as reality TV.

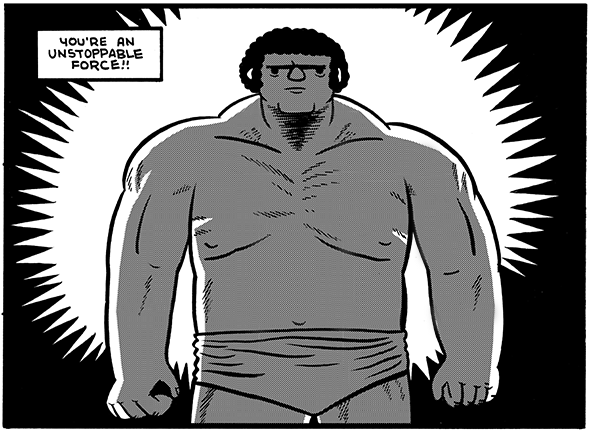

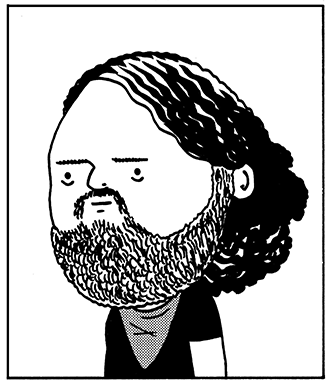

Courtesy of First Second

By that time, Roussimoff was already dead. His body’s growth finally outpaced the capabilities of his heart in 1993, and his legacy was forever suspended in the shape of a gimmick. In panel after panel, Brown shows Roussimoff downing giant drinks, releasing giant laughs, emitting giant farts, and talking big. In the background of this hulking image, Brown sketches in complicating details—fans heaving garbage from the stands, barflies goading him into violence, late-night talk show hosts reducing him to a sight gag, and doctors delivering increasingly alarming diagnoses.

Roussimoff was an easy target, and in Brown’s telling, that made him sympathetic to the little guy even as he was susceptible to the grotesqueness everyone seemed to expect from him. (In one tale, Roussimoff gives a homeless woman dinner money, then crudely jokes that he’d like to eat her out). “That’s the only story they tell about him: How mean he was,” Hulk Hogan said in a 2010 interview that Brown illustrates to kick off the book. “People don’t get it. … There was never a situation where he could be comfortable. He was a seven-foot-four giant. … If you really understood what he went through and what he was all about, he was a gracious person with a kind heart.”

But even these winkingly revelatory interviews—wrestlers “telling the truth” about one of their own—fail to transcend Roussimoff’s impenetrable exterior. Brown’s cartooning is sensitive enough to capture the grand spectacle of the ring and the quiet tension of life outside of it, but he’s not a reporter, and his source material is limited. He relies heavily on shoots with living wrestlers (who are incentivized to protect their industry and their place in it, and seem particularly enamored of gross-out tales) and WWE-branded retrospectives (which mined his legacy for even more returns after his death). The only other major biography of Roussimoff, Andre the Giant: A Legendary Life, was published by the WWE; a 1999 documentary, Andre the Giant: Larger Than Life, was released by WWF Home Video. With Roussimoff gone, Brown is left to examine the traces left by the kayfabe Roussimoff lived, and the glorified press releases that surfaced after his death.

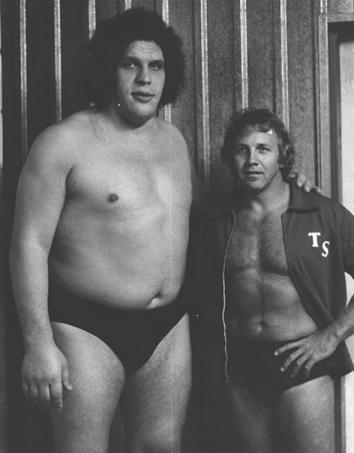

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Not that Brown’s book is cartoonish. The graphic approach allows him to prioritize Roussimoff’s subjectivity in all the gossip his colleagues have tossed around: Wrestling documentaries never captured Roussimoff’s crestfallen face as strangers hurled slurs, or followed him into the operating room when doctors performed surgery, Roussimoff’s body laid out on two pushed-together tables. But the demands of the medium also flatten the wrestler’s experience. Even when accounts conflict, Brown is forced to mold scraps together into a singular narrative to keep the action moving frame by frame. He is transparent about this process: “I’m not sure how truthful Hogan is being throughout this interview,” he says in the notes at the end of the book. “He tends to exaggerate all of his stories.” The bar tale, which has been retold countless times by pro wrestling figures who weren’t present at the scene, is plausible at best. “The details of the story often change,” Brown writes. “Was André picked on like this? Almost assuredly yes. Could André flip a car with two people in it? Most assuredly yes.” Did he actually do it? I’m not convinced.

Meanwhile, the wrestling business—which made billions selling these cockamamie stories to fans—escapes Brown’s scrutiny. In parsing Roussimoff’s life from his legend, Brown never quite pins the industry that exhausted the former in order to build (and capitalize off) the latter. “Money is the only morality in professional wrestling. Things that make money are good,” Brown notes in the preface, and Roussimoff “made more money than any other wrestler.” We get a taste of the business’ internal machinations in a scene from 1973, where Vince McMahon Sr. discovers the giant, pronounces him not quite big enough, and urges him to 86 his nimble wrestling moves so he appears to be “an unstoppable force” who doesn’t “move for nobody” in the ring. McMahon takes Roussimoff’s act on the road to ensure he’s never overexposed in any market, allowing his legend to build until “by the time you get back to town, you’re ten feet tall!!”

This proved a lucrative strategy for the McMahons, but the toll it took on its employee remains uninvestigated. In the book, Roussimoff’s handlers appear sympathetic when he requests leave to undergo surgery, but professional wrestling’s responsibility to its star appears to end there. In Brown’s telling, we watch Roussimoff lurch from the surgery table to the wrestling ring to the corner bar over and over again until the day he dies. What we don’t quite see is the wrestling empire the McMahons were building upon his back the whole time. Today, Vince McMahon Jr.—who was born a year before Roussimoff, and inherited the WWE business model from his dad—is still kicking with a reported worth of $750 million.

In the years since Roussimoff’s death, some professional wrestlers have exposed the kayfabe behind the kayfabe: The WWE’s exposure of its own artifice ultimately served to conceal the industry’s dubious treatment of the men it turned into characters. “Everybody believes that, physically, wrestling is fake; that nobody gets harmed,” former pro wrestler Allen Ray Sarven told the New York Times in 2010. When he retired, Sarven says he was left with very real neurological damage and no health or retirement benefits from the executives who profited off of the “fake” blows. “Death Grip,” a 2007 CNN feature on the dangers of pro wrestling, reported that between 1983 and 2003, at least 64 wrestlers died of drug overdoses, heart attacks, or suicide before the age of 40.

Brown’s book ends just before Roussimoff’s death at age 46. From the executive’s perspective, though, a wrestler’s economic potential lives on after he’s gone, in the form of promotional products, sponsored biographies, and successors to the storyline: In 1995, World Champion Wrestling billed wrestler Paul Wight as “the Giant,” outfitted him in a one-shoulder black singlet identical to Roussimoff’s, and floated the rumor that he was Roussimoff’s biological son. (He’s not.)

Brown glances at these complicated truths of the wrestling industry, but he lacks the material to spin this reality into a storyline of its own. The book is most honest in its first scene (where Brown draws Hulk Hogan himself talking about Roussimoff, revealing the potentially-compromised perspective of the storyteller up-front) and its final scene, which manages to be both touching and scatological (and which Brown admits was basically invented). Telling André Roussimoff’s full story requires a more dedicated reporter, or else a more improvisational touch. As it stands, André the Giant offers a peek at the man behind the myth, but not much scrutiny of the industry that’s still taking his money. Once wrestling was through with him, André Roussimoff left behind more of a legend than he did a life.

—

André the Giant: Life and Legend by Box Brown. First Second Books.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.