Margaret Ferguson has edited children’s books for over 30 years, and is now the publisher of Margaret Ferguson Books/Farrar Straus Giroux Books for Young Readers. She talked with three-time Caldecott Honor winner and MacArthur Fellow Peter Sís, about the process of editing a picture book and how Sís’ new children’s biography of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Pilot and the Little Prince, was made.

Margaret Ferguson: When and why did you start illustrating picture books?

Peter Sís: I became a picture book illustrator out of desperation or necessity because I came to Los Angeles from Czechoslovakia to make films and it didn’t work out, and someone sent my pictures to Maurice Sendak, who called me in Los Angeles and said, “So you want to be in children’s books? You need to live in New York.” So in 1984, I moved to the city and at first I was assigned to illustrate other authors’ books. Finally, three years later, Frances Foster signed me up to both write and illustrate my first book, Rainbow Rhino.

Ferguson: I find that there are more steps involved when an author and an illustrator are not one and the same. It begins with an exchange with the author about who we think should illustrate the book and it is followed by the editing of the text without an illustrator involved. And then once an illustrator makes a dummy with the sketches, I show it to the author. The author and the illustrator rarely communicate so I am the go-between. Is this your experience when you illustrate other people’s stories?

Sís: Everything very much depends on the editor. I didn’t understand in the beginning that the editor didn’t want me to know the author. I’d make an effort to meet the author, but it would end up being a disaster because then I had the author telling me what I should be doing. When I do my own books, I take it as more of my own confessional, but when I illustrate for other people, it is intriguing because I feel like I shouldn’t be stepping too much into the limelight. It’s like playing the piano while someone else is singing.

Ferguson: It is always fun to match stories and illustrators—I have to find someone whose work reflects the tone and energy of the text, and not just anyone will do. We used to have portfolio days when illustrators would come in and show their work, but that doesn’t happen so much now because of the Internet. But still, whenever I see art I like—in a magazine, for instance–I clip it and put it in my idea box.

Sís: Ursula Nordstrom was famous for finding artists in unlikely places. Maurice Sendak was a window designer and she just came across one of his windows. Everyone was looking to find a talent.

Ferguson: Why did you decide to write The Pilot and the Little Prince?

Sís: I read The Little Prince when I was a boy, but I never thought about who wrote it and what his inspiration might be. My father came to visit me in New York City in 1987, and when we took a walk along Central Park South, he pointed out where Saint-Exupéry lived when he was in New York. I had no idea he had lived here and that this is where he wrote The Little Prince.

I project myself into all my books. Since I am also from another country, when it came to Saint-Exupéry I thought, Oh, he must have been so sad living in New York, away from home and unable to speak English. But with all my books I start to project too much of my own ideas, my own life, my own feelings, and that’s when it takes an editor to keep things on track.

Ferguson: The Pilot and the Little Prince is the first book we worked on together because our dear friend and your wonderful editor for more than 20 years, Frances Foster, became ill and retired. So when I came on board you had gone through many dummies, had completed some illustrations, and had a rough text. Is this the way you usually work?

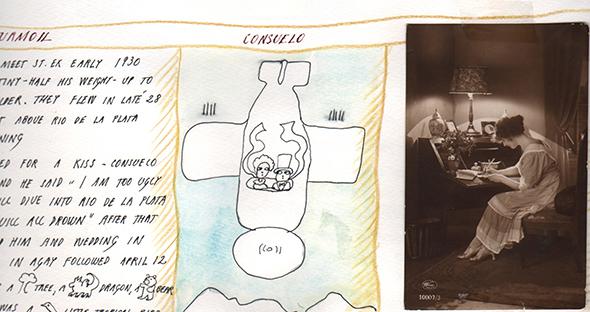

Sís: I’m a visual person, so it always starts with a picture, and then I get obsessed with the idea, sometimes too much. I have these blank books in which I take notes, and I add postcards and other physical items. This book of ideas gives me a sense of what the book will be, and then I scale it down from there to something closer to the final work.

Courtesy of Peter Sís

For The Pilot and the Little Prince, in the beginning I was just trying to doodle his life and see where it was interesting. I made a chart of his life and it was amazing because he was always crashing his planes and surviving! There was a lot of information I couldn’t use because there was just no way to fit it all in. From this first book of ideas, I made more and more concise dummies, until I felt I had it right.

Really, ideally what would happen is that I would have a dream, wake up in the morning, draw the experience, write something down, bring it to you, you would look at it and say “This is perfect!” and I would go and paint it and we would be done with it. But there are so many steps in creating these books and they take time—it sounds ridiculous now because you see the finished book and it’s like, Well, that looks easy.

Ferguson: Yes, it’s like a big puzzle—trying to get all the pieces to come together. I usually sort out the text, make a type dummy, have the illustrator do sketches, and then go to finished art. I like to spend a lot of time fine-tuning the dummy so all the pieces are in place when an illustrator goes to finishes. I imagine that editing a picture book is a lot like editing a film. It is about pacing, deciding what is truly necessary, and taking into consideration that turning a page creates a moment too—sometimes it is a pause, sometimes it leads to a surprise. Often once the final art is in and the book is laid out, it becomes apparent that something in the text is not necessary because the art says it all.

Courtesy of Farrar Straus Giroux Books for Young Readers

Sís: The ideal thing would be that we agree from the beginning what all the final art will be, but it doesn’t usually work that way. If you create an amazing piece of art, you are reluctant to give it up, but sometimes only when you are done do you see that it doesn’t serve the story. There have been pieces I’ve insisted on putting in a book only to realize later that I was mistaken. You learn to give things up.

Ferguson: But it’s hard because you get attached. In The Pilot and the Little Prince, we also had to think a lot about pacing because there is so much information.

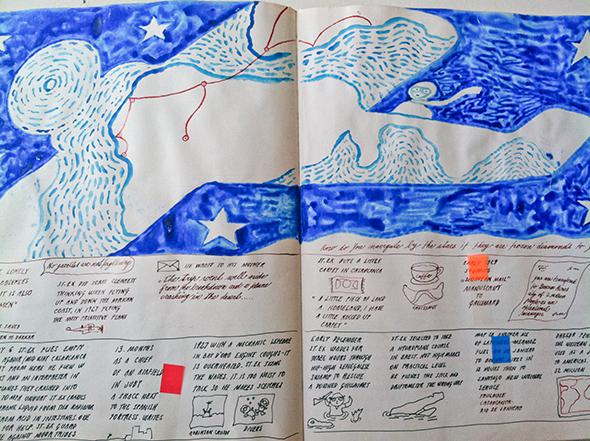

Sís: In this book there are spreads that cover many years of Saint-Exupéry ‘s life. So we have a busy scene on one double-page spread and then when you turn the page there’s something quieter.

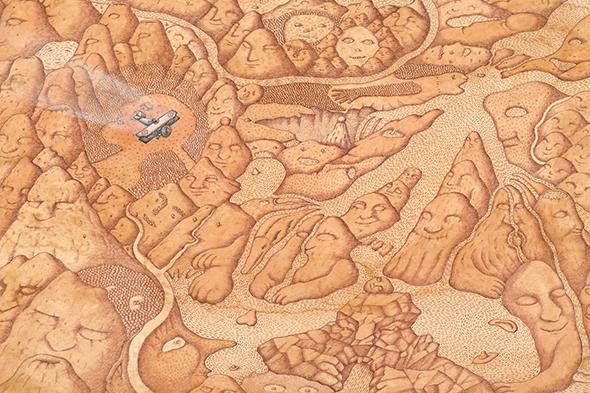

Ferguson: There are also some wordless pages to emphasize text from a previous page—like the spread that shows Saint-Exupéry “following the face of the landscape.”

Courtesy of Farrar Straus Giroux Books for Young Readers.

Sís: It is easy to say now that we knew where all the art should go, but we never know until it is done. I get lost in it. Maybe behind each book there is a struggle, but maybe not. Maybe that’s just me.

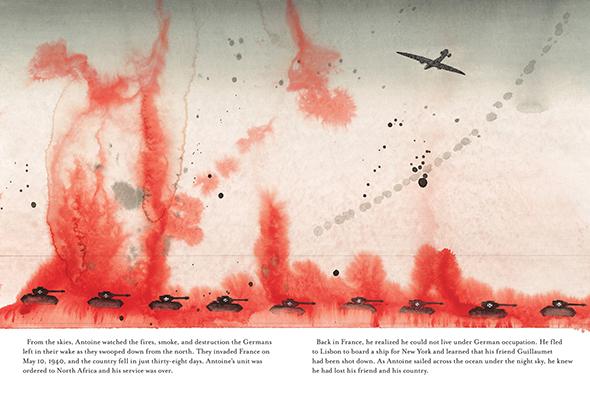

Ferguson: I think it is a struggle more often than not. It is amazing to me how your art creates so much emotion using different styles. I am thinking about the moment when Saint-Exupéry ‘s friend died when he crashed his plane in the ocean, which you handled in a tiny icon that just shows water rings, and then the war scene, which is big and bold—both are equally effective and moving. I know that you sometimes do many pieces of art for one illustration—how do you know when you’ve created the right one?

Sís: I can say I know right away, but of course I don’t. It is important to see how one picture follows another and to decide where you feel something is missing and need to add a different piece of art. There’s a lot of advantage to having people around you. For example, I liked the illustration of the war with the bleeding red in The Pilot and the Little Prince but wasn’t daring enough to say I wanted that picture in the book. But then you said you liked it and my wife said she liked it, so I started to believe it was the right one. For some of the illustrations I did three variations before we picked one.

Courtesy of Farrar Straus Giroux Books for Young Readers.

I had an experience a few years ago when I was told I could have as many pages as I wanted to illustrate the story, and it just went on and on and on and I did not know where to stop!

Ferguson: In that way it is a blessing that picture books have a limited number of pages to work with—usually 32, but this book has 48 pages.

For many years I admired your relationship with Frances and the intuitive way you worked together. When I took over the project I read and reread your backlist titles in order to absorb your writing style and voice. Every editor works differently, but I tried to ask questions Frances would have. And I know she was very much on your mind too during every stage. I am so sorry Frances wasn’t able to complete this book with you, but I feel honored and lucky to have had this journey with you.

Sís: Thank you so much.

—

The Pilot and the Little Prince by Peter Sís. Farrar Straus Giroux Books for Young Readers.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.