Imagine liking a singer so much you travel across the country to see him. You invade his private spaces; commit his every song to memory; change the way you dress, walk, and talk to be more like him. When people ask about your past, you answer the way he might, instead of telling the truth.

This kind of behavior might make you a subject of David Kinney’s new book The Dylanologists. But it might make you Bob Dylan himself.

When Bob Dylan arrived in New York on Jan. 24, 1961, he was a Woody Guthrie pilgrim. He talked like he came from Oklahoma instead of Minnesota and told stories of ramblin’ that would have fit in Bound for Glory. He sought out the folk singer, who was suffering from Huntington’s chorea. On the weekends Dylan would sit by Guthrie’s hospital bed and play him songs.

The Dylanologists are just as obsessive about Dylan. In the age before digital music, tape collectors strapped audio equipment to their bodies and pursued rare recordings like jewels from the Pharaoh’s tomb. Bill Pagel purchased the ticket from Dylan’s prom, his high chair, and ultimately the home in Duluth where Dylan was born. Elizabeth Wolfson vacationed to California so she could drive by Dylan’s Malibu home. Security found her wandering the grounds and turned her away. The most famous of the Dylanologists, A.J. Weberman, was so consumed with trying to figure out the transcendental message behind Dylan’s music he was caught looking through the singer’s trash.

Woody Guthrie gave shape to Bob Dylan’s life and gave him an identity. That’s a powerful relationship, and it’s what makes the Dylan fanatic such an interesting topic. From the 1960s, when Dylan was first called the “voice of a generation,” he and his music have shaped entire lives. He’s not just the guy playing in the background at the deli. He’s soundtracking marriages and inspiring in listeners a deeper understanding of themselves. Dylanologists credit Bob for driving them to certain careers or relationships.

He doesn’t want the credit. Dylan’s career has been propelled by his effort to stay one step ahead of his fans. He shed the protest-singer label almost as fast as they gave it to him, and he’s ditched every category they’ve tried to put him in ever since. Wherever he is right now, he’s on the run.

After reading this series of profiles, it’s hard not to share Bob Dylan’s feelings about his most devoted fans. “Get a life, please,” he told one interviewer about the devotees. “You’re not serving your own life well. You’re wasting your life.” Kinney doesn’t make this argument explicitly. His book is not unlike a Bob Dylan song—he paints a picture and then you’ve got to interpret it yourself—but the conclusion seems plain: The life of the Dylanologist is often a wasted one.

One woman who hitchhikes from show to show winds up the victim of a serial killer. Another superfan commits suicide. Others become disillusioned and wonder what they did with their lives. “Why am I such a mess?” asks Charlie Cicirella during a nervous breakdown in line for a Dylan show in December of 2005. “Why is my life such a mess?” Cicirella tells Kinney that listening to Dylan for the first time “was the first time he could ever remember not feeling alone.” But what did that inspire him to do? Based on the book, the answer is: Attend lots of Dylan concerts and fight for a spot in the front. Others can quote Dylan’s words but don’t have much to say on their own. A.J. Weberman’s dumpster-diving search for the ultimate Dylan sends him off the deep end. He concludes that “Blowin’ in the Wind” is actually a racist screed: “I wasted my fucking life on this shit.”

It’s not all this way. Kinney offers a sympathetic portrait of some of Dylan’s fans. Mitch Blank is such an expert Dylan completist that he has become a music historian who Martin Scorsese consulted on his Dylan documentary. Scott Warmuth rescues the reputation of those obsessed with tracking the literary allusions in Dylan’s works. This clan of the tribe gets a bad name because their pursuits get tedious fast, leading to long lists of footnotes and boring debates over whether Dylan is a plagiarist. But Warmuth, a disc jockey, musician, and writer, is not just a squirrel gathering nuts. On his Dylan blog he’s looking not simply to rack up new discoveries, but to make a case: Dylan is arranging his borrowings and allusions into a collage with a hidden structure, delivering a subtextual message behind the lyrics.

The most illuminating character sketches in Dylanologists come from fans of Dylan’s “religious period,” which spanned from roughly 1978 until 1981. Many biographers treat this time as a talentless detour, but it offers a useful way to distinguish between the fan who uses Dylan as a crutch and those who use him as a walking stick. Dylan’s religious fans don’t think he’s a god, but a preacher, someone who illuminates a larger truth, one he’s also searching for. He’s taking fans on that journey. Dylan feels better when he can provide illumination rather than answers. “I’m the first person who’ll put it to you,” he once said, “and the last person who will explain it to you.”

Michelle Engert offers a secular example of the kind of fan Dylan might like. After following him across the globe during the early 1990s, Engert drops off the Dylan trail and returns to school. She studies maquiladora laborers because Dylan had made her want to help the underdog. She becomes a public defender. Because she had hitchhiked and lived on the streets following Dylan, she’s more savvy than she might otherwise have been. “Bob Dylan made her a better lawyer,” Kinney concludes.

These characters are closer to the larger swarm of Dylan hobbyists—people like me, I hope—who have been influenced by the singer but not asphyxiated. There was a time in my life that I fit the profile of one of Kinney’s Dylanologists. I spent the night on the street outside Tower Records in New York to get tickets to one of Dylan’s 1993 Supper Club shows. I lined up in Charlottesville at daybreak to be in the front row. I spent part of my last summer before college touring around after him. I have two bookshelves devoted to books about him. “It was the first poetry that spoke my own language,” I might say about Dylan—as Dylan said about Jack Kerouac.

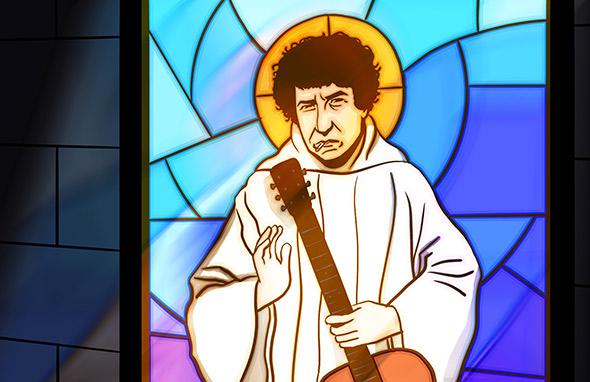

Photo by Marjan Osman Gartland

Dylan is the artist that helped me take hold of the world when I was in high school, a time when you’re looking for explanations anyway. He taught me about the power of words, taking risks, justice and faith—secular and religious. He offered some pretty practical notions about love, regret, and willpower that sounded catchy to the ear.

Dylan got the first crack on influencing those ideas, so he’s still there when I touch them again later in life. Music that helps you form your identity reminds you of who you are, and can immediately take you back to those moments of self-creation.

Kinney’s deeply reported book delineates the difference between Dylan’s obsession with Guthrie and the obsessions of the most extreme of the Dylanologists. Dylan used his obsession to become his own creative force. The Dylanologists, meanwhile, are entombed by their passion. They are very active—road miles accumulate, tapes are collected, and they are enlivened by the briefest glances Dylan gives them from the stage—but in the end they seem dissipated by the relationship. At some point, the Dylan fan has to get off the bus, the way Michelle Engert did, the way Dylan got off the Guthrie bus. It is a paradox of the many characters Kinney describes. They have listened to Bob Dylan for so long, but some of them have not heard.

—

The Dylanologists: Adventures in the Land of Bob by David Kinney. Simon and Schuster.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.