Patrick Leigh Fermor, one of travel literature’s most colorful, beguiling pedestrians, famously decided to walk across Europe when he was 18. Why not? He’d failed out of every school he’d gone to, after all, had given up on joining the army, and was living a somewhat-too-dissipated life in London among the aging remnant of the Bright Young Things. So, in the winter of 1933, equipped with a rucksack, walking stick, military greatcoat, puttees, and the Oxford Book of English Verse, he hopped on a boat to Rotterdam, Netherlands, pointing his hobnailed boots in the direction of what he’d always call Constantinople (not Istanbul), where he’d arrive in just over a year.

Eighty years later, we finally have the complete account of that trip. But it was a long road getting there—a kind of parallel journey. In 1962, Holiday magazine asked Fermor to write an article on “The Pleasures of Walking,” which he took as a chance to revisit the “Great Trudge” of his youth. He managed to cover the first two-thirds of the trip in a mere 70 pages, but the conclusion ballooned into a book of its own. Fermor wanted to call it Parallax, to underline the dual vantage of adolescence and middle age. His long-suffering publisher suggested A Youthful Journey instead. As it happened, it became neither as, busy building a house in the Peloponnese, Fermor abandoned the project altogether. By the time he took it up again, 10 or so years later on, he’d decided to start from the beginning again and write not one book but three. A Time of Gifts, which covers his walk from Holland to the middle Danube, was published in 1977. Between the Woods and the Water followed nine years later, taking him as far as the Iron Gates separating the Balkan and Carpathian mountains and ending with the words “TO BE CONCLUDED.” With the posthumous publication of The Broken Road: From the Iron Gates to Mount Athos, it kind of is.

The Broken Road is something of a stand-in for the long, long awaited third volume that Fermor planned to write. Assembled by his biographer Artemis Cooper and British writer Colin Thubron, it’s basically the manuscript of A Youthful Journey polished up a bit, though Cooper and Thubron claim that “scarcely a phrase” in it is theirs. Why Fermor couldn’t complete the trilogy himself is unclear. He was, by all accounts, a slow writer, working and reworking each sentence so diligently that a friend, according to Cooper, once accused him of “Penelope-izing”—unraveling the day’s work every night like Odysseus’s wife. But by the time he died, in 2011 at the age of 96—a real feat for someone who, by his own accounting, smoked 80 cigarettes a day for most of his life—“Volume III” had been in the works for more than half a century. Perhaps in his later years, as Cooper suggests in her biography Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure, the author may have felt that “the whole subject was beginning to feel stale, barren, written out, and he feared he no longer had the strength to bring it back to life.”

Fermor’s torment may also have been a case of writerly perfectionism gone awry, as The Broken Road will seem, by most standards, plenty alive. Fermor’s deeply layered narrative, as before, intersperses fetishistically beautiful descriptions with historical tidbits, personal asides, and fanciful imaginings. He remains endlessly fascinated by local costume, folklore, genealogy, songs, and the doings of monks and muezzins, bouncing happily from peasant village to aristocratic schloss, from student digs on the Black Sea to Romanian country villa. He meets a girl (“half captured Circassian princess, half Byronic heroine”), stomps grapes, smokes hash, witnesses a celebratory riot in a Bulgarian café when it’s announced that someone’s murdered the Yugoslavian king, downs countless glasses of raki and slivo, investigates the Hasidim, theorizes on the breeding of mermaids, and sings German songs backwards to entertain a Bulgarian maid. Arriving in Bucharest, he accidentally checks into a brothel, thinking it’s a hotel, to the great entertainment of all, then charms his way into Romanian high society—opera, heaps of caviar, an excess of brandy—and passes out on the floor of an artist’s flat. He reads The Brothers Karamazov and Don Juan, and somehow always manages to find a bed for the night, usually a free one.

Still, this is a different Europe than that of the first two books—one toward which Fermor seems more ambivalent than the Mitteleuropean splendor he’s passed. Out of the old Holy Roman Empire and the familiar shadow of Western Christendom, he’d entered the strange oriental world of the Balkans—a region so recently free of the Ottoman yoke that it remained steeped in both Turkish culture and oppression’s palpable effects. There are fewer castles and a great many more huts. There’s more racial hatred too—Jewish/Romanian, Romanian/Bulgarian, Bulgarian/everyone but Russians—a legacy of the region’s violent past. Of course, Fermor’s zestful catalogue of certain Balkan cruelties—like the blinding, by Basil the Bulgar-Slayer, of a thousand-man army, leaving one of every hundred soldiers an eye “so that the rest might grope their way home to the czar” —reveal that, for a 19-year-old at least, bloodthirstiness was part of the region’s romance.

Fermor takes obvious delight in language, picking up words as one might souvenirs: In Romania, for instance, “the best word I had ever heard for irretrievable gloom: zbucium, pronounced zboochoum, a desperate spondee of utter dejection, those Moldowallachian blues.” The Broken Road positively drips with exotic names, ethnic designations, and obscure vocabularies. A dog is “passant, sejant then couchant,” and beekeepers go about “their Georgic business…mobled in muslin, calm-browed comb-setters and swarm-handlers of the scattered thorps.” Thorps! Fermor’s linguistic revelry also results in descriptive passages that verge on the purple, with images layered one over the other in a positive conflagration of sense: “Cauliflowers sailing overhead, towing their shadows twisted and bent by the ravines, like ships’ anchors, across the whale-shaped undulations, or hovering in the high mountain passes as lightly as ostrich feathers, or sliding along the horizons in pampas plumes. The setting sun turned each of these into the tail of a giant retriever.” The passage, in case there’s any doubt, describes clouds.

Actually though, hard as it is to believe, A Broken Road is a great deal less “written” than the previous two books—it was essentially a draft, unspangled with the oodles of adjectives that customarily embellish Fermor’s Byzantine prose. A representative description of a building from Volume I, by comparison, displays his gifts at full polish: “From the massed upward thrust of its buttresses to the stickle-back ridge of its high-pitched roof it was spiked with a forest of perpendiculars. Up the corner of the transepts, stairs in fretted polygonal cylinders spiralled and counter-spiralled, and flying buttresses enmeshed the whole fabric in a radiating web of slants.” This sort of thing might seem a bit steroidal to some, but the verbal fireworks go a long way toward recapturing the rapturous enthusiasm with which the young Fermor seems to have shone. “I was unboreable, like an unsinkable battleship,” the author reflects in The Broken Road. “My mouth was as unexactingly agape as the seal’s to the flung bloater. … I might, judging by my response to phenomena for most of these thousands of miles, have been a serious drug addict.” The tumultuous rush of his prose mimics the drug-like thrill that reality had for him then, and this—getting the reader as high on his words as he was on life—was what Fermor saw as his greatest challenge, 30 years on. The Broken Road tends more toward introspection than euphoria at times, frankly discussing the periodic bouts of depression that were euphoria’s flip side and Fermor’s doubt in his memories. “Were the domes tiled or were they sheeted in steel or lead –or both, as I boldly set down a moment ago? Or is it the intervening years that have tiled and leaded and metalled them so arbitrarily?”

Often the older writer admits to recalling little or nothing about a particular time, and often he confesses to being “almost irresistibly tempted to slip in one or two balloons from a later date.” One such “balloon” intrudes during Fermor’s walk south along the Black Sea coast from Varna, Bulgaria. The unknown coastline had proved rockier and less passable than anticipated, the night was dark, and both he and his flashlight had just fallen into a pool, the latter irretrievably. Bleeding from his forehead, Fermor found himself, as he writes, “sliding, crawling on all fours, climbing up ledges draped with popping and slippery ribbons of bladderwrack,” and close to despair. Rounding a cliff, he stumbles at last into a cave, where he finds a group of shepherds and fisherman cozied up for the night with a campfire and a bunch of goats. What follows is one of the most exhilarating set pieces to be found in travel writing anywhere: Having been fed, dried, and liquored up, Fermor joins his hosts in a night of ribald fun, in which a fisherman performs a rebtiko, an ancient dance that’s like a history of the Balkans writ small: “All the artifice, the passion for complexity, the hair-splitting, the sophistication, the dejection, the sudden renaissances, the flaunting challenge, the resignation, the feeling of the enemy closing in, the abandonment by all who should have been friends, the ineluctability of the approaching doom and the determination to perish, when the time came, with style,” Fermor writes, is sublimated in movement, offering “consolation and an anodyne in individual calamity.” It’s a thrilling insight in a linguistic whirl of a scene.

It also, apparently, never happened. As Cooper reports, the scene is more or less a conflation of a night Fermor spent in a fisherman’s hut on the Black Sea and an evening lost along the coast of Mount Athos, in Greece, some weeks later. It’s reputedly not the only incidence of this sort of thing: According to Cooper, a vaunted trip on horseback across Hungary seems not to have happened either. Fermor told her he feared “the reader might be getting bored of me just plodding along” and so put himself on a horse. Such fictional accents, Cooper gently suggests, were part of Fermor’s “making a novel of his life”: He didn’t invent, per se, but created “new memories” shaded by imagination. A more convincing explanation is that by the time Fermor sat down to write about the walk, not only was it 30 years in the past, but he had lost all of his journals from the time—the first stolen, the rest left unclaimed in storage after the war—and had just memories, real or not, for reference.

The distance between living and writing is responsible too for the shadow European history cast over Fermor as he sat down to write his Trudge books. Fermor was in Germany in December 1933: Hitler was in power, and the rise of nationalism was apparent in the streets, where heil-ing stormtroopers would “become performing seals for a second … as though the place were full of slightly sinister boy scouts.” In Vienna, in February 1934, he arrived in the middle of the riots between the country’s anti-communist militia and Social Democrats, the beginning of a political shift that would culminate in the Anschluss some years on. But the young Fermor, having little interest in politics, didn’t notice at all. “I wasn’t a political observer,” he yells at a Bulgarian friend who’s rebuked him for wanting to visit the hated Romania. “Races, language, what people were like, that was what I was after: churches, songs, books, what they wore and ate and looked like, what the hell!” If the young Fermor, busy with parties, drinking, smoking, sex (only delicately implied of course—he’s British), failed to foresee the consequences of Nazism’s rise, the older one certainly does. “I am maddened,” he wrote in 1963, “by not having seen, written, looked, heard.”

And so despite the author’s obvious attempts to preserve, somewhat, the innocence of his youthful self, the books are haunted by the knowledge of what was about to transpire—the fact that, as Fermor writes in The Broken Road, “Nearly all the people in this book, as it turned out, were attached to trails of powder which were already invisibly burning, to explode during the next decade and a half, in unhappy endings.” His accounts of the colorful ways of gypsies and Jews in particular can’t help but have a foreboding, even elegiac tang, no matter how they are written, and the same is true, in The Broken Road, of the landscape itself. Returning to Bulgaria and Rumania in 1990, Cooper reports, Fermor was “utterly crushed,” refusing even to talk about what he had seen: not just poverty and hunger, but picturesque villages replaced by concrete farm-workers blocks, Bulgaria’s Turkish culture completely gone, hulking Soviet towers rising from what had once been pristine wilderness.

It is no surprise then that Fermor, toward the end of his life, despaired of recapturing the innocent joy with which he’d crossed this vanished landscape and eventually gave up trying. A Youthful Journey ends quite abruptly—in midsentence, in fact—a few days before the journey reached its ultimate goal. For whatever reason, Fermor failed to take many notes at all in Constantinople. The few he did make are included here, to represent, I guess, the “broken road” of the title: “Slept till six o’clock in the evening, then, waking up, thought it was only the dawn, having overslept twelve hours, so turned over and slept again till Jan 2nd morning,” he writes of the day he arrived. Eleven days later, he was in Greece, where The Broken Road concludes, with a coda of sorts to the official account: Fermor’s perambulation through the Orthodox monasteries of Mount Athos. (As a side note, this monastic peninsula, unlike most of the places Fermor visited, seems largely unchanged. It remains, among other things, forbidden to females of all species, with the notable exception of cats.)

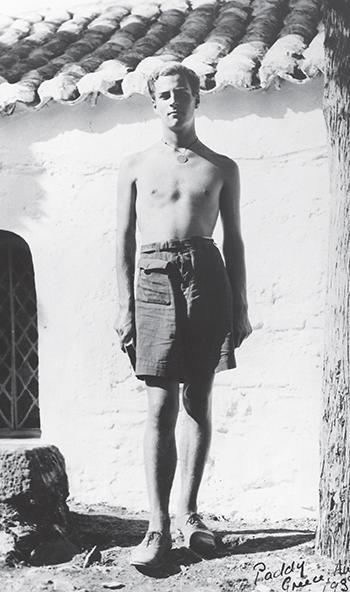

The text of this part comes from Fermor’s so-called Green Diary, the sole survivor of the heap of near-talismanic journals he carted about on his walk. This one he left in Romania with his first great love, the Princess Balasha Cantacuzène, who, despite years under fascism and behind the Iron Curtain, took care of it, returning it to Fermor during a secret visit in 1965. It’s a useful document, if only for the purpose of comparing the unfiltered prose of Fermor’s teenage years with the polished, many-fretted sentences that he’d produce later on. The episode of walking along the cliffs and falling into the sea, recast so brilliantly some 150-pages back as a microcosm of Balkan life, appears here just another night really, drinking with some woodsmen in a hut. One gets the feeling that Fermor would have objected to the diary’s inclusion, but in a way it’s a perfectly appropriate end. Here, lonely, tired, and somewhat fed up with the “unilluminated literalness” of Balkan life, the boy first encounters a country that he would come to love above all. Two years later, after a charmed period of rest in Romania and Greece, he’d join the intelligence services and serve in Crete as a liaison to the native partisans, eventually masterminding a hussar-ish plan to kidnap the Nazi general in charge of the occupying forces and transporting him, by mule, over the mountains, and then to Cairo by boat. He would write two books on Greece and settle permanently there in 1964 with his wife Joan, in a small fishing village in the Peloponnese. There, as a mature perfectionist fighting a losing battle against his exuberantly prolix younger self, he’d try to write what would eventually become The Broken Road. In some ways, though, the 20-year-old Paddy we leave at Mount Athos would end up outliving him.

—

The Broken Road: From the Iron Gates to Mount Athos by Patrick Leigh Fermor. New York Review Books Classics.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.