For evidence of our species’ tendency toward complacent self-regard, you don’t have to look very much further than the name we’ve given ourselves. (My Latin is a little rough, but Homo sapiens basically translates as “clever man.”) We see ourselves largely in terms of our knowing; our place in the natural order of things is at the top, as the ones who have it figured out. And it’s pretty obvious, too, that it was a biologist who got to do this naming because the name reflects our conception of ourselves as knowers and understanders of the world—as scientists by nature. There’s another way of thinking about what defines us, though, that is just as reflective of our essential qualities: We are creatures of narrative, makers and consumers of stories. And the things we don’t understand about the world and our place in it—the areas that remain dark to our scientific sapience—have always provided fertile territory for that narrative inventiveness. We understand the world by making it up. “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” as Joan Didion famously put it; we’re a species of Scheherazades, narrating for our lives.

The presence of Scheherazade’s tutelary spirit is one you feel throughout Isabel Greenberg’s The Encyclopedia of Early Earth, an inventive graphic novel about the telling of stories, about making things up and staying alive. Although the whole thing is held together by a simple framing narrative (a story about a storyteller who sets off in search of a missing piece of his soul), the main substance of the book is in its diversions, in the stories that unfold within that frame. Greenberg’s imagined world is a patchwork map sewn together from the territories of culturally ingrained mythologies—ancient Greece, the Hebrew Bible, Norse legend, and the above-mentioned Arabian Nights, among others. Part of the considerable charm of the book, at least for a particular kind of pedantic reader (i.e., this one), is in spotting these allusions and inspirations, and the clever means by which she integrates them and deviates from them.

The comic opens with a setup straight out of the Book of Exodus: Three sisters walking together along the banks of a lake in the Land of Nord (a polar region peopled by the broadly Inuit-like Nords) find an abandoned baby in a basket. They look after him together, but tensions arise—as tensions inevitably must in such scenarios—over who loves him the most and should therefore get to raise him as her own. So the whole non-nuclear family piles into a canoe and paddles out to the iceberg home of a medicine man to whom “the Nords deferred … in all matters of importance.” There’s a King Solomon-style standoff among the sisters, and a decision is made to split the child, via unspecified sorcery of soul division, into three distinct but physically identical little boys. Each sister gets her own version of the baby, and things work out tolerably well for a while.

It soon becomes apparent, however, that the three boys are turning out somewhat one-dimensional personalitywise; there’s an angry one who’s only ever angry, a philosophical one who’s only ever philosophical, and a cheerful one who’s only ever cheerful. The sisters realize they’ve made a dreadful mistake and so contrive to have the medicine man recombine the boys into one relatively normal whole. But it further transpires that the soul had actually been split, through some basic thaumaturgical blunder, into four parts, one of which managed to escape into the ether, thereby leaving the boy, who has now become his clan’s storyteller-in-residence, feeling internally riven and incomplete. So he packs his belongings and his adorable little husky into a canoe, and sets off on a quest to find the missing bit of his soul, telling stories along the way.

Greenberg’s style, as a storyteller and as an illustrator, is both straightforward and sophisticated. Her drawings have the elegant and open simplicity of woodcuts; there’s an aesthetic of artful childishness and a sort of wry, amiable tension between the old-style fables and origin myths she deals in and the contemporary language she uses. In one Cain and Abel-like story about the murderous origins of the Viking-like Dag and their ancient quarrel with the neighboring Hal, an elder brother refers to a younger as “a wet little fart” and “a pussy.” (If, by the way, you think your 10 year old can deal with this sort of mild saltiness, you could do a lot worse than steering them in the direction of this book.)

Greenberg has a lot of metafictional fun with the theme of storytelling. About halfway through, she introduces a cartographer named Mancini Panini who is famous for his beautiful maps, thought to have been the first to chart Early Earth. (Panini looks pretty much identical to the medicine man from Nord, and to a shaman from the South Pole. This is a running joke throughout the book—“a plot device that will never be explained, so deal with it!”—as is the fact that these supposedly wise old men tend to prove incompetent.) Panini’s methodology turns out to be radically unsound; a severe agoraphobic, he gathers intelligence for his maps by sitting in his tower and peering through his telescope, and then sending out three trained monkeys in pedal boats, armed with paper and pen, to survey the terrain. His map of the world, we are told, is “generally agreed by explorers to be completely useless since it is almost entirely wrong on every level,” but he is “possessed of an excellent imagination and a steady and meticulous drawing hand, and so the maps can be valued as things of beauty.”

Greenberg portrays this scientific failure as integral to a kind of artistic success. Empirically, he’s feeling around in the dark, afraid to even venture out into the territory he’s supposed to be surveying. She doesn’t overstrain the metaphor, but our man Panini is elegantly suggestive of storytelling (of art itself, really): the work of making beautiful maps of unknown territories. This is what Greenberg is about here, in her light-fingered way: inventing the world from scratch and coming up with origin myths that are—and this is sort of the point of such myths—almost entirely wrong on every level but valuable as things of beauty. (And being entirely wrong, of course, doesn’t necessarily preclude the capturing of certain kinds of truth.)

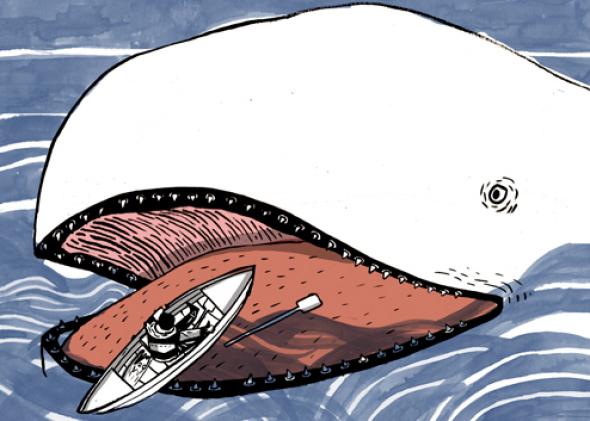

Courtesy of Lydia Garnett

Her Early Earth, we learn, is the result of a competition between a god named Birdman, his son Kid, and his daughter Kiddo. The three bird-persons of this trinity, literal inventors of worlds, are, in terms of characterization, Greenberg’s most well-drawn figures. As gods, they’re more Hellenic than Abrahamic, which is to say mischievously and playfully human. Birdman emerges, at some unspecified point in Early Earth’s prehistory, from an egg that just appears out of nowhere. (“Don’t ask how it got there, OK,” we are instructed. “Every story has to have a beginning and this one begins with an egg, floating in an infinite, empty cosmos.” Your standard chicken-or-egg cosmogony problem, handily dealt with.) He then lays two eggs of his own, from which emerge the son and daughter who eventually decide, out of cosmic childish boredom, to have a world-making contest. Early Earth turns out to be Kiddo’s creation, a vast, complex world that she carries in her hair; in a fit of jealous petulance at her creative success, her brother cuts off her hair, causing it to tumble into infinity, growing in size and complexity as it falls. With this story, Greenberg is slyly rewriting the rigidly patriarchal source code of the culturally enshrined narratives she’s drawing from. (See also her inversion of old-crone fairy-tale tropes to produce a heroic giant-slaying great-grandmother.) She is, in this sense, a bit like a cartoon Angela Carter.

All this stuff might be strenuously whimsical in a work of prose fiction, but the loveliness and composure of Greenberg’s illustration and her playful narrative tone make for an endearing combination—and the whimsy is pretty much inseparable, anyway, from the myth-riffing project as a whole. Her stories, like those she alludes to and borrows from, are creative misreadings of the world, beautiful maps drawn from incomprehension and imagination. In all its trapdoored complexity, its stories within stories about stories, The Encyclopedia of Early Earth is a funny and touching celebration of the narrative species that we are.

—

The Encyclopedia of Early Earth by Isabel Greenberg. Little, Brown.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.