Does each one of us have a personal madeleine, waiting to be discovered? There is so much good writing out there about food that it’s easy to take for granted the ability of a hot fried oyster or a creamy slice of buttermilk pie to suck us into the vortex of memory. So an eater can be forgiven for feeling insecure if she has not found her personal madeleine. The emotional pull that food has over us is such an established truism that every bowl of tired pasta seems as though it has the potential to be a life-changing event.

But it was not always so. The Puritan streak that animated early American life looked askance at too much enjoyment of food, which could be taken as gluttony. The whole of the first Thanksgiving gets little more than a sentence in a first-hand account of the Pilgrims, which says simply, “For three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation.” With a few notable exceptions (Thomas Jefferson and Mark Twain, for example), not many Americans devoted themselves to waxing rhapsodic about creamed onions or roast mutton. Cookbooks were straightforward affairs, and most home cooks focused on stretching their food dollar as far as possible.

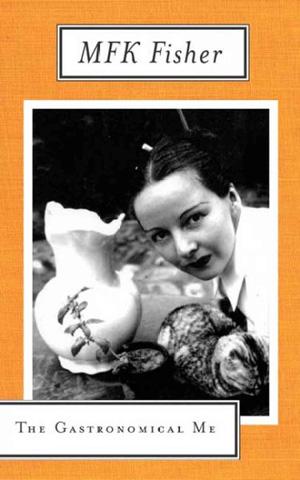

Enter M.F.K. Fisher, née Mary Frances Kennedy. In 1929, she fled her family home in California for France with her first husband, and spent the next few years discovering a culture that proudly embraced a more epicurean tradition. All the while, she was learning to combine a growing love of food with a passion for writing. The beautiful, impetuous Fisher was drinking sherry, learning French, and eating everything from snails to soufflés to potato chips “fried in real butter.” And she was taking notes.

Her books eschewed page after page of recipes in favor of an amalgam of memoir, travelogue, essay, and of course, food writing. In his 1942 review of Fisher’s How to Cook a Wolf the New York Times’ Orville Prescott noted that cookbook writers were not known for their writing talents, “… until a knowing lady who signs herself austerely M. F. K. Fisher began conducting her one-woman revolution in the field of literary cookery.”

The following year, Fisher published The Gastronomical Me, which celebrates its 70th anniversary this month. The collection of essays, which stretches from her childhood to her life in France, the beginning of World War II, the dissolution of her first marriage and the death of her second husband, marked Fisher’s emergence as one of the great voices of her time. It is telling that Fisher, who wrote so hedonically of food, so often chose to discuss hunger in these pages. The book is not about dumb indulgence but the constant roving of human appetites, be they for love, power, money, or food. She relates a train trip with an uncle while she was still an adolescent, when her teenage habit of blithely ignoring the menu was finally quashed by a stern look. “I looked at the menu, really looked with all my brain, for the first time,” she writes, and then orders her iced consommé and sweetbreads sous cloche with determination and poise. We are all hungry, she tells us, but we must remember to make choices, not drift to whatever is at hand. Our hunger unites us; our choices, in restaurants and in life, make us individuals.

Fisher’s sensual accounts of the connection between food and emotional inner lives severed food writing from kitchen drudgery. She begins another essay with an account of her landlords in France, a family with which she and her first husband boarded. But she interrupts herself from a straightforwardly gastronomic account, describing the “cold meats and salads and chilled fruits in wine and cream …” only to stop herself and realize, “When I think of all that, it is the people I see. My mind is filled with wonderment at them as they were then, and with dread and a deep wish that they are now past hunger. They were so unthinking, so generous, so stupid.” The reader travels with her from a jolly 1930s French kitchen to the desolate aftermath of World War II. For Fisher, food is not just evocative; it is a unique language she wields to explain subtleties glossed over by the written word.

Despite critical acclaim (W.H. Auden once declared her America’s best prose writer), “she never sold more than a few thousand books,” Judith Jones, one of her editors, said of her early career. Fisher herself felt that she was initially dismissed as a writer on the grounds that “it was woman’s stuff, a trifle.” For decades her books sometimes went out of print, but the 2004 re-release of The Art of Eating, a compilation of her best-known work, including The Gastronomical Me, helped to introduce her work to a new generation of readers. She is the subject of a few biographies but remains slightly outside of the mainstream zeitgeist while claiming an expanding group of followers, including Ruth Reichl, former New York Times food critic and author of the memoirs Tender at the Bone and Comfort Me With Apples, who said that “growing up in the 1950s, if you wanted to read this kind of stuff about food, there wasn’t anybody else.”

Fisher wrote The Gastronomical Me at a whirlwind pace; she claimed afterward that it was written in 10 weeks. It was not as though she had nothing else on her mind. The love of Fisher’s life, Tim Parrish, had shot himself almost exactly two years earlier, after years of a debilitating, painful illness that required the amputation of one leg. More pressingly, she was pregnant and unmarried, still scandalous in 1943. After telling friends and relatives she was on a classified government assignment, she withdrew to Altadena, Calif., where both the baby and the manuscript gestated. She finished the book in July, just after her 35th birthday. The baby, Anne Kennedy Parrish, was born in August. She never revealed the father.

North Point Press; Edition Unstated

The Gastronomical Me covers some of the dramatic highlights of her life, but this is no gushing tell-all. Her authorial persona is eccentric at times, but dignified and intelligent. Her first husband is represented in the book but entirely eclipsed as a central player by her second, Parrish, called Chexbres on the page. She’s deliberately ambiguous about when one relationship ended and the second began. Her biographer, Joan Reardon, once complained, “On the one hand, [Fisher] tells all—kind of a confessional element. On the other hand there are whole gaps, there is a lot of subterfuge.” But few people read literary memoirs for strict devotion to chronology or unalloyed truth. Fisher’s accounts of her anxiety and melancholy in pre-war Europe, her heartbreak at watching the death of her true love, ring true, 70 years later.

In the preface to Gastronomical Me, Fisher wrote:

Like most other humans, I am hungry … it seems to me that our three basic needs, for food and security and love, are so mixed and mingled and entwined that we cannot straightly think of one without the others. So it happens that when I write of hunger, I am really writing about love and the hunger for it.

With these words a thousand of today’s food memoirs were seemingly launched. Gabrielle Hamilton’s 2011 Blood, Bones & Butter is one of the most successful heirs to Fisher’s oeuvre. Hamilton traces her development as a popular chef, but dwells with equal weight on her troubled relationship with her parents and her fraught marriage. Her prose echoes The Gastronomical Me as it traces the development of a woman and an eater. “Hunger was not general, ever, for just something, anything, to eat,” Hamilton writes. “My hunger grew so specific I could name every corner and fold of it. Salty, warm, brothy, starchy, fatty, sweet, clean and crunchy, crisp and water, and so on.” Annia Ciezadlo’s 2012 Day of Honey brings food memoirs to a war zone, and this year’s Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking, by Anya von Bremzen, attempts to tell the story of Soviet Russia through food. The most serious subjects are now viewed through a culinary lens, just as Fisher insisted that the lead-up to war or the privations of the home front could be tackled with discussions of Chianti and hot buttered toast. (Hardly a woman’s trifle.)

Brillat-Savarin, grandfather of the food essay and a favorite of Fisher’s, once wrote, “The pleasure of the table belongs to all ages, to all conditions, to all countries, and to all areas; it mingles with all other pleasures, and remains at last to console us for their departure.” Fisher lived through a world war, three marriages, the suicides of her greatest love and her brother, and the isolation of an out-of-wedlock pregnancy in 1940s America. But she continued to write about the pleasures of the table, and to share this consolation—small though it might seem at times—with anyone possessed of a hunger like hers.

—

The Gastronomical Me by M.F.K. Fisher. North Point Press.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.