Excerpted from A Reader’s Book of Days: True Tales From the Lives and Works of Writers for Every Day of the Year by Tom Nissley, out now from Norton. Slate will be excerpting the book every day this week.

BORN:

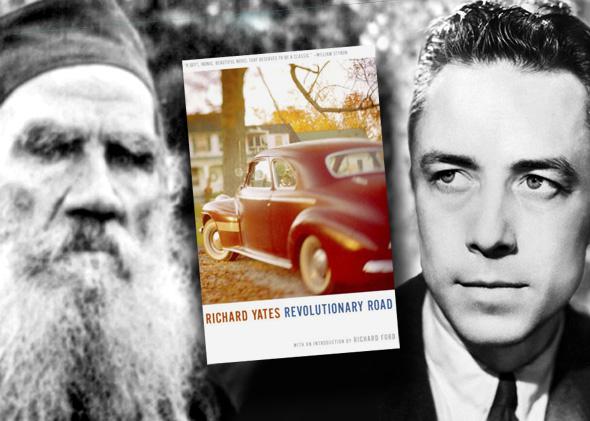

- 1913: Albert Camus (The Stranger, The Plague, The Fall), Dréan, French Algeria

- 1954: Guy Gavriel Kay (Tigana, The Summer Tree), Weyburn, Sask.

DIED:

- 1910: Leo Tolstoy (The Death of Ivan Ilyich), 82, Astapovo, Russia

- 1992: Richard Yates (Revolutionary Road), 66, Birmingham, Ala.

1874: In the Times of London, Arthur Rimbaud placed an advertisement: “A PARISIAN (20), of high literary and linguistic attainments, excellent conversation, will be glad to ACCOMPANY a GENTLEMAN (artists preferred) or a family wishing to travel in southern or eastern countries. Good references. A.R. No. 165, King’s-road, Reading.”

1896: Eleven-year-old Ezra Pound published his first poem in the Jenkintown Times-Chronicle, a limerick on the defeat of Williams Jennings Bryan by William McKinley that begins “There was a young man from the West.”

1900: Perhaps it was his immersion in the culture of the 12th century for the study that would become Mont Saint Michel and Chartres that made Henry Adams so receptive to the shock of the new 20th century at the Paris Exhibition of 1900. In a November letter to his old friend John Hay, Adams marveled at the mysterious power of the electric dynamos on display there, and over the next seven years this shock became the engine behind his singular autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams, driven by the contrast between the forces of medieval and modern life (“the Virgin and the Dynamo,” in his words) and by Adams’s own history as a child of the colonial era making his way in the modern one, “his historical neck broken by the sudden irruption of forces totally new.”

1955: While traveling the country for what would become one of the most influential photography books of the century, The Americans, Robert Frank was arrested in McGehee, Ark., and interrogated for 12 hours in the city jail—“Who are you? Where are you going? Why do you have foreign whiskey in your glove compartment? Are you Jewish? Why did they let you shoot photos at the Ford plant? Why did you take pictures in Scottsboro? Do you know what a commie is?”—before being released.

1972: Flying home from Rome to Colorado on this day to vote for McGovern, James Salter assured Robert Phelps, “Your life is the correct life … Your desk is the desk of a man who cannot be bought.” In their mutually affectionate and admiring correspondence, which began with a fan letter from Phelps about Salter’s novel A Sport and a Pastime, Salter was the novelist more admired than popular and Phelps the impossibly well-read journalist who lived in fear of never rising above what he considered hackwork to write something great: “You are wrong about my ‘life,’ ” he replied to Salter. “For 20 years, I have only scrounged at making a living … Somewhere I took a wrong turning. I should not have tried to earn my living with my typewriter. I should have become a surveyor, or an airline ticket salesman, or a cat burglar.”

—

Reprinted from A Reader’s Book of Days: True Tales from the Lives and Works of Writers for Every Day of the Year by Tom Nissley. Copyright © 2014 by Tom Nissley. With permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.