For a couple of years, I wrote a horoscope column for my college paper under the name “Claire Connection.” (The pseudonym was meant as parody, but—as I discovered when an actual astrologer by that name wrote my editor a threatening email—it wasn’t.) Despite the flippancy with which I approached the task then, I do still find myself turning to the horoscopes from time to time. Because you needn’t buy what astrology’s selling to be interested in the conjunction it forces between human make-believe and the arbitrary structure of things, a curious relation that the discipline (if one may be allowed to call it that) throws into relief: We’re unwilling to give up on freedom, serendipity, and plain old hard work—but we don’t want to just be a fluke. There’s a deep reassurance to be had in feeling oneself part of some great cosmic cycle.

Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries, an 848-page novel currently favored for the Man Booker prize [Update, Oct. 15: It won!], situates itself within this dilemma from the start. In the opening scene, the Scotsman Walter Moody, newly arrived in the New Zealand gold town Hokitika in 1866, unwittingly disrupts a secret meeting: “The twelve men congregated in the smoking room of the Crown Hotel gave the impression of a party accidentally met. … indeed, the studied isolation of each man as he pored over his paper, or leaned forward to tap his ashes into the grate, or placed the splay of his hand upon the baize to take his shot at billiards, conspired to form the very type of bodily silence that occurs, late in the evening, on a public railway.” The description of this seemingly “accidental” arrangement—one that is in fact “studied,” and “conspired,” conjures not so much the train as the theater, and, sure enough, each player has been blocked into his proper corner. (This is true of Moody as well, as it happens, though he seems to have wandered in from the wings.) The Luminaries is, among other things, an experiment in predetermination. By extinguishing every coincidence, it turns literature into the same kind of problem as astrology: Do we want structural interpretation to dictate narrative, or is it best when a story’s structure, as one character puts it, “always changes in the telling”?

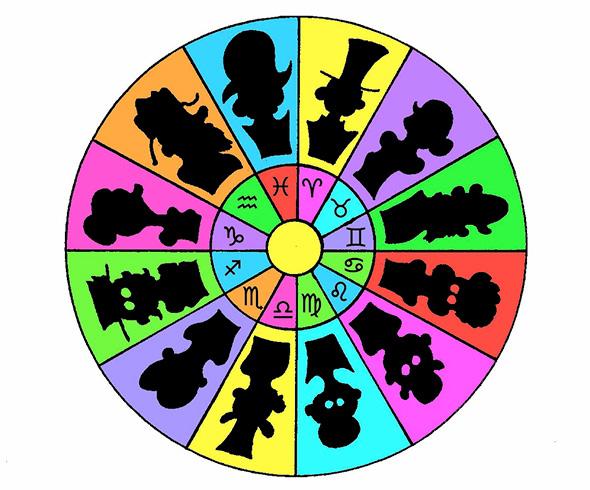

One way to read Catton’s novel is as kind of antipodean crossword, in which the clues lead one not to a filling-in of blanks but to the erasure of content—so the solution is little more than the grid into which everything fit. Each of the novel’s 12 sections begins with an astrological chart for the date and location of its setting, which dictates what and how events will unfold. A “Character Chart” at the front of the book indicates 12 “stellar” characters, each associated with a sign of the zodiac and a location representing one of the astrological houses. These determine both the character’s destiny and his personal characteristics. Example: One chapter indicates that the constellation Aries—represented here by the Maori hunter Te Rau Tawhare—is in the third house, which in astrology has to do with brotherhood, communication, etc., all of which make sense in the context of the plot. In addition to these zodiac-affiliated characters, there are seven “planetary” ones that rotate throughout the astrological chart from month to month. One quickly discovers that the chapter titled “Venus in Capricorn” will primarily consist of a tête-à-tête between the characters associated with Venus (the alluring Lydia Wells) and Capricorn (Aubert Gascoigne, a clerk).

The titular “luminaries”—the astrological designation for sun and moon—are the opium-addicted whore Anna Wetherall and the prospector Emery Staines. In astrology, the sun more or less represents exterior, visible things, and the moon personal, internal ones, ergo so do these two—but they often reflect one another, exchanging qualities. Emery, in what is clearly a lunar phase, describes their relationship as “a connexion, by virtue of which he feels less, rather than more, complete, in the sense that her nature, being both oppositional to and in accord with his own, seems to illumine those internal aspects of his character that his external manner does not or cannot betray, leaving him feeling … doubled when in her presence, and halved when out of it.” And then there is Crosbie Wells, a drunkard whose murder is the still point around which the whole novel turns: Earth, in other words.

As if this were not enough, the very length of the novel’s 12 sections has been planned in advance, beginning at 360 pages (not coincidentally, the number of degrees in a circle), and declining progressively until the final part of just three. The number of chapters per section also systematically wanes: The first has 12, the second, 11, and so on, down to one. By the end, the book had dwindled to almost nothing—chapters present the barest sketches of events, even as they attempt a final, revealing explanation of the novel’s mysteries. Meanwhile, the little explanatory précis at each chapter’s head slowly waxes to eclipse it: commentary stealing the function of story.

Encased in this postmodern complexity is a plot—a “sphere within a sphere,” as one chapter has it—about as pre-modern as it gets, a mystery having to do with hidden gold, a prostitute’s suicide attempt, and the disappearance of a wealthy man. Arbitrary-seeming circumlocutions (“d—ned”), chapter headings a la Dickens (“In which we learn …”), the word “connexion,” and the authorial second person plural are all de rigueur. Vividly set in the gold rush of the mid-1860s, The Luminaries is, on this level, a fairly straightforward page-turner in the “sensation novel” mode, with the full complement of Victorian clichés: whores, bastard brothers, eavesdropping, a séance, murder, shipwrecks, impersonation, a dead baby, purloined letters, and a pistol hidden in someone’s bosom, to start. Ignore the astrology, and the characters are stock: an Irish reverend with bad teeth, a couple of Chinese “Johnnies,” a conniving madam with a sideline in the occult, noble savage, scar-faced villain, guileless naif, and so on. Everyone has secrets. Everyone remembers things just when doing so is most convenient. Events are often narrated second-, and even third-hand, explanations given, and scenes unfold within scenes within scenes, creating layers of revelation. The initial theatrical impression’s sustained: Two characters find themselves momentarily “fixed in a tableau, the kind rendered on a plate, and sold at a fair as a historical impression”; Moody’s hotel room is “furnished very approximately, as in a pantomime where a large and lavish household is conjured by a single chair.” One might use similar metaphors for the novel as a whole.

Throughout, an authorial voice chimes in to assist, warn, and regret. Part of its function is to force the novel’s parts rather blatantly into line: “We shall here excise their imperfections … we shall apply our own mortar to the cracks and chinks of earthly recollection, and resurrect as new the edifice that, in solitary memory, exists only as a ruin.” The “we” is hugely contrived, but then contrivance is what The Luminaries rests on. Lunar cycles mandate the narrative’s return it to its beginning; a full year of star charts races the last quarter of the novel through 1865; even the name “Hokitika,” which in Maori means, approximately, “Around. And then back again, beginning” is unequivocal. The introductory “Note to the Reader” (another period nod) even lays out the plot’s themes, associating it with the Age of Pisces and things “Piscean” in quality: “mirrors, tenacity, instinct, twinship, and hidden things.” Not just contrivance, but highly visible contrivance, underlies everything: Unlike, say, Bolaño’s similarly lengthy 2666, The Luminaries contains—nay, advertises—the keys to its own exposition.

Robert Catto

The question this raises is what effect such structural contrivances have on a reader’s pleasure—whether what we call “novel” and especially “big, ambitious novel,” is supposed to exist at the level of plot, or sentence, or on this third, impositional plane. Yes, Catton’s language is beautifully tended-seeming, luminous in a mode appropriate to the 19th century cadence of her tale. There are no sloppy sentences, nothing that strikes one as unintentional or out of her control. Her observations too are astute, as when two men at a party bear “the distant, slightly disappointed aspect of one who is comparing the scene around him, unfavourably, to other scenes, both real and imagined, that have happened, and are happening, elsewhere.” So it’s possible to read the book with pleasure strictly on the level of what one might call its “literary merits”—or it would be, if only its author would let you.

She doesn’t. Neither are we allowed to fully engage on the level of characters or plot—the astrological contrivance is too shifty for that. Moody, for instance, represented by the planet Mercury, is initially placed to be a kind of go-between with the reader, following, as he does, just slightly behind the “stellar” players as they explain their involvement in events; Thomas Balfour (Sagittarius), a shipping magnate, seems set up as our central “explainer.” But then the heavens shift, Mercury moves out of Balfour’s sign, and these two are flipped offstage like figures in a paper theater while others pop up to replace them. In fact, once the structural conceit becomes apparent, every detail of the novel glows with such intention that it almost blinds you to the pleasures of story. One becomes obsessive: Is the divider, the Greek letter Φ, used for its symbolic affinity to the golden mean? Or does it stand for the constellation Ophiuchus, sometimes called the 13th zodiac sign? Catton never allows you to relinquish the impression that there are answers to be found, and that like a crossword, the novel might be no more than a sophisticated amusement.

Whether one appreciates this point is the question that emerges, in its sly, interesting way, in and through the novel’s pseudoscientific groundwork. How and why, when so much care is manifest, do we feel manhandled? Do subjective responses suffer when an author—or the cosmos, in this case—dictates every element of the work to the point that even after 848 pages both character and plot can be drowned out by their own determinant structure? As in astrology, these questions have to do with relation, primarily that between the “warm” pleasure of emotional engagement and the “cool” pleasure of a game—pleasure as activity versus pleasure as state. That Catton has provided a “solution” to her novel might strike some as diminishing its ability to generate the jagged thrill of the big (usually male-penned) novels it draws comparison to by virtue of sheer bulk—Gravity’s Rainbow or Ulysses say, or indeed 2666. It may, by virtue of this, seem far less “serious” or worthy.

Catton, when The Luminaries was first published, was 27, and when I mention this to my group of 30-ish, novel-less peers, the reaction generally takes the form of whatever the opposite of schadenfreude is: from ugh and oh … so I hate her, to she’s the child of someone famous, and rich, and went to a fancy school, right? These are ugly, unfair (and some will inevitably say sexist) reactions, but ugly or not, they are worth acknowledging, and not entirely irrelevant either, it so happens. Because jealous displeasure with Catton’s age-to-successes ratio stems from the same root as our discomfort with something as perfectly formed as her novel: a longing, in the midst of being impressed, for that truth inhabited by things spontaneous, ragged-edged, wounded, or imperfect, for things that are granted the freedom to fail. This is the point The Luminaries makes, in the end, having gone so far to the other extreme—its seamlessness delivers us around, and then back again. Perhaps, as Catton’s Emery Staines explains, “True feeling is always circular—either circular or paradoxical—simply because its cause and its expression are two halves of the very same thing!” That’s because it is people who both make novels and feel things about them—and while we might be conceived in chaos, we tell ourselves stories so as not to be.

—

The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton. Little, Brown.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.